Author: Joe Barr

Kino is a video editor that allows you to produce your own video masterpieces using only free and open source software. With it, you can capture and edit clips from your video camera, add titles, insert still images, create transitions between scenes, and output the result in a number of formats. Best of all, it’s easy to learn to use. But don’t rely on the version in your distro — grab the 1.1.1 release from SourceForge.net and build it yourself.

Downloading and compiling the latest version of Kino may be a bit of a bother for some, but it’s well worth the trouble for Ubuntu users, because the current Ubuntu package is the less capable 0.92. I downloaded the tarball, but it wouldn’t compile until I found and installed the list of prerequisite packages for an earlier release of Ubuntu. I then ran configure, make, and sudo make install. On my dual-core AMD 3200+ box with 2GB of memory, the compile took nearly seven minutes.

Kino supports only FireWire (IEEE-1394) for capturing video from your camera. No FireWire, no capture — USB is not an alternative. USB is supported only to control external devices like jog and shuttle wheels that you may want to use for editing and playback.

Because Kino uses dvgrab to capture video, you’ll either need to run it as root, tweak permissions for the 1394 device, or add your user to the video group. The last method is the preferred solution, as the first two may create insecurity. If you’re running Ubuntu 7.04, you’ll also need to edit /etc/udev/rules.d/40-permissions.rules to change the line that begins KERNEL==”raw1394″ to end with GROUP=”video” instead of GROUP=”disk”. You may need to log out and log back in for the changes to take effect.

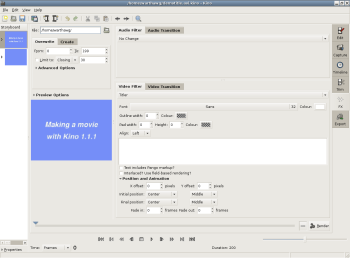

With that bit of housekeeping taken care of, connect your camera to your IEEE-1394 port, turn it on, and start Kino. The Kino UI (see figure) is driven by the mode selected by one of the six icons arranged vertically along the right side of the window. Kino starts up in Edit mode; to capture video from the camera, click on the Capture icon.

The Capture UI provides five control buttons aligned beneath the video window that allow you to enable and disable VTR control of the attached camera, start video capture, stop video capture, capture a still image, and mute the sound during capture. While VTR control is on, you’ll see the typical icons to play, pause, rewind, and fast forward the tape, as well as position the current frame at the start of the tape, start of the scene, previous frame, next frame, or the end of the video. To capture video, edit the file name to your liking and click capture. The camera will start playing the video and continue until you tell it to stop.

Editing clips

Once you’ve downloaded some video, you can start editing it. If you don’t already have a clip loaded, you’ll need to open one to get started. Be careful as you open clips, because unless you specify Insert Before or Insert After before selecting a file, Kino will assume that you’re starting a new movie and close or discard all the clips you may already have opened.

The Edit UI provides icons to allow you to save the currently displayed frame as a single image file; insert a new file before or after the current scene; undo or redo the last change; cut, copy, or paste the current scene; split the current scene; join the current and following scenes; or cycle between 50%, 100%, and fit-to-window zoom.

The Edit UI uses thumbnails of each scene, stacked on top of each other along the left side of the window, to show a movie’s storyline. You can quickly negotiate a longish video simply by clicking on the clip you want to edit and going directly to it.

Actually, there is more data than just a thumbnail in the storyboard. If you grab the bar dividing the video image window and the storyboard and drag it to the right to increase the space available for it, you can see the file name, starting frame number, and duration in frames of each item. You can see additional information about each clip at the bottom of the left column, including the timecode, file format, audio specs, and video specs. Even better, you can easily rearrange scenes in your movie by dragging and dropping the thumbnails in the storyboard.

Beneath the video window is a timeline with a pointer showing the location of the currently displayed frame within the video. Small gaps in this timeline indicate splits, which may be the result of having stopped and restarted the camera during filming, places where multiple files have been joined, or where you have created a split while editing.

A typical edit session involves removing unwanted portions of a clip. You can use the VTR controls noted above to find the frame where you want to start cutting, click on the split scene icon on the menu bar, then do the same for the last frame you want to remove, and finally click on the cut scene icon. It’s fast and easy to edit scenes this way.

Titles and transitions

Once you’ve trimmed away the parts you don’t want and rearranged the scenes as dictated by your video muse, you’re ready to assemble the pieces into a final product. Click on the second icon from the bottom along the right side of the Kino UI to enter the special effects mode.

You can add a title to existing frames or create new frames for your title. Begin by creating new frames, 200 of them, containing nothing but a light blue background, as the backdrop for the titles, and saving them in a separate file, because you will have more work to do before the title scene is finished. Enter a file name in the text box in the upper left corner of the window, then click the Create tab in the panel immediately below it. Next, select Fixed Colour from the drop-down menu that appears beneath the tabs, set the number of frames to 200, and click on the color selection icon to bring up a color wheel. Pick the color you want, click OK, and you’re good to go.

Once you’ve told Kino what you want it to do, all that’s left is to render the frames accordingly. Click the Render button in the bottom right corner of the window and Kino will create them. When the render is finished, Kino will display a thumbnail showing the new scene in the Storyboard along the left side of the UI.

Rendering can by a compute-intensive process, which is another way of saying that you’ll find yourself waiting for it to finish. Rendering 200 frames with a single color and no text took only about four seconds on my desktop system. Rendering those frames again with a few lines of scrolling text added 30 seconds to the chore. Depending on the amount of rendering to be done, and the heavy lifting required, you could end up waiting an hour or more for it to finish. This helps explain why dual core processors are becoming de rigeur for desktop video work.

Now you can add background music and text to the blank title frames. Click on Overwrite, then, in the Audio effects panel immediately to the right, click on Audio Filter and select Mix from the drop-down menu. Enter the file name of the music you want to use in the text box. I used samples of music I found on the Creative Commons Web site. After rendering the scene again, the frames now contain the specified audio.

You can preview the title scene at this point by clicking on the play VTR control along the bottom of the window. Before you do, you may want to click on Preview Options and unselect the Loop and Low Quality checkboxes.

Now move to the panel below the Audio effects and click on Video Filter. Open the drop-down menu beneath that tab and select Titler. A new window will appear beneath the tabs and menu from which you can select the font, size, and color for your text. When you’ve finished entering the text, placement, and any animation effects you may have selected to move the text up, down, left, or right across the frames, click on render again.

Don’t preview the latest version of these frames from within the FX interface — instead, click on the Edit icon and play it from there. If you play it from within FX, movement will be slow and sound will be choppy, and you’ll think that either you’ve done something wrong or that Kino isn’t working properly. I’m not sure which is true; it might be the hardware begging for more speed, another core, more memory, or all of the above. If your video becomes very large or complex, you may see similar degradation even while in edit mode. If you do, check your work by playing it completely outside of Kino with VLC, MPlayer, or another video player.

I wasn’t happy with the results the first time I saw my titles floating across the screen. To change what I had done, I clicked Undo from the menu bar, returned to the FX UI, made changes, and rendered the frames again.

To combine your finished title with the rest of the movie, click the Insert After icon on the menu bar, then select the movie from the file directory. Transitions between scenes, between the title and the following video, or between adjacent video scenes in the Storyboard are just as easy to do.

Select the scene you want to transition from in the Storyboard, then click on FX. In the Video panel, click Video Transition rather than Video Filter. You’ll find a list of transition techniques you can apply, including Dissolve, Barn Door Wipe, Push Wipe, and Composite. If nothing on the Transitions menu appeals to you, click on the Video Filter tab and experiment with Fade In, Fade Out, Blur, Soft Focus, Superimpose, or one of the other filters listed. There are enough possibilities to lure your inner Bergman out into the open.

Since my daughter and son-in-law are both race car drivers, I’ve been making a movie about family night at the races. One of the most common events at Saturday night races is the waving of the yellow flag, usually resulting a break in the racing action while things are tidied up on the track. It seemed logical to me to use a standard transition between scenes when this happened, so I took created one.

First, I found an image of a flag and modified it slightly by adding text and color. In Kino, I created a 75-frame scene of a single color, then, using Video Filter -> Superimpose, I added the image of the flag to the frames I created.

The final step is exporting your work into a standard video format. Doing that is just as easy in Kino as everything else has been. Start by clicking the Export icon. You can export in one of several DV formats, save still images, export audio only, or save MPEG or Ogg Theora format video.

If you want to create an Ogg video, click the Other tab, enter a file name for your movie without an extension, then select Ogg Theora (ffmpeg2theora) from the drop-down menu of tool choices. Assuming you want best quality, click Render at this point and wait. If you’re going to put the video online, you may want to choose one of other Profile choices to consume less bandwidth.

That’s a wrap!

I’m very impressed with Kino 1.1.1. It has improved a lot since we looked at the 0.9.2 release. It is not as powerful and full-featured as commercial offerings like Final Cut on Mac OS X or other choices for Windows, and there are still a few rough edges. But it is more than powerful enough for personal use, perfect for making films about my grandkids, puppies, donkeys, and races. In fact, Kino stands above Final Cut in its intuitive design and ease of use. Editing, especially, is much faster and easier in Kino.

Kino can do a lot more than I have described here. If you’re looking for a video editor to run on Linux, install the latest version of Kino and give it a whirl.

Click on the image below to view a sample video built entirely with Kino 1.1.1.

Category:

- Graphics & Multimedia