Today was a gorgeous day in San Francisco. The temperature was in the mid-60’s, the sun was shining, and there was a light breeze. The forecast is for similar weather all week – just in time for Oracle OpenWorld 2018. I flew in to cloud cover, but it burned off between baggage, finding my ride, and the drive from SFO to the city. I…

Click to Read More at Oracle Linux Kernel Development

Key Happenings on the First Day of Oracle OpenWorld 2018

To BeOS or not to BeOS, that is the Haiku

Back in 2001, a new operating system arrived that promised to change the way users worked with their computers. That platform was BeOS and I remember it well. What I remember most about it was the desktop, and how much it looked and felt like my favorite window manager (at the time) AfterStep. I also remember how awkward and overly complicated BeOS was to install and use. In fact, upon installation, it was never all too clear how to make the platform function well enough to use on a daily basis. That was fine, however, because BeOS seemed to live in a perpetual state of “alpha release.”

That was then. This is very much now.

Now we have haiku

Bringing BeOS to life

An AfterStep joy.

No, Haiku has nothing to do with AfterStep, but it fit perfectly with the haiku meter, so work with me.

The Haiku project released it’s R1 Alpha 4 six years ago. Back in September of 2018, it finally released it’s R1 Beta 1 and although it took them eons (in computer time), seeing Haiku installed (on a virtual machine) was worth the wait … even if only for the nostalgia aspect. The big difference between R1 Beta 1 and R1 Alpha 4 (and BeOS, for that matter), is that Haiku now works like a real operating system. It’s lighting fast (and I do mean fast), it finally enjoys a modicum of stability, and has a handful of useful apps. Before you get too excited, you’re not going to install Haiku and immediately become productive. In fact, the list of available apps is quite limiting (more on this later). Even so, Haiku is definitely worth installing, even if only to see how far the project has come.

Speaking of which, let’s do just that.

Installing Haiku

The installation isn’t quite as point and click as the standard Linux distribution. That doesn’t mean it’s a challenge. It’s not; in fact, the installation is handled completely through a GUI, so you won’t have to even touch the command line.

To install Haiku, you must first download an image. Download this file into your ~/Downloads directory. This image will be in a compressed format, so once it’s downloaded you’ll need to decompress it. Open a terminal window and issue the command unzip ~/Downloads/haiku*.zip. A new directory will be created, called haiku-r1beta1XXX-anyboot (Where XXX is the architecture for your hardware). Inside that directory you’ll find the ISO image to be used for installation.

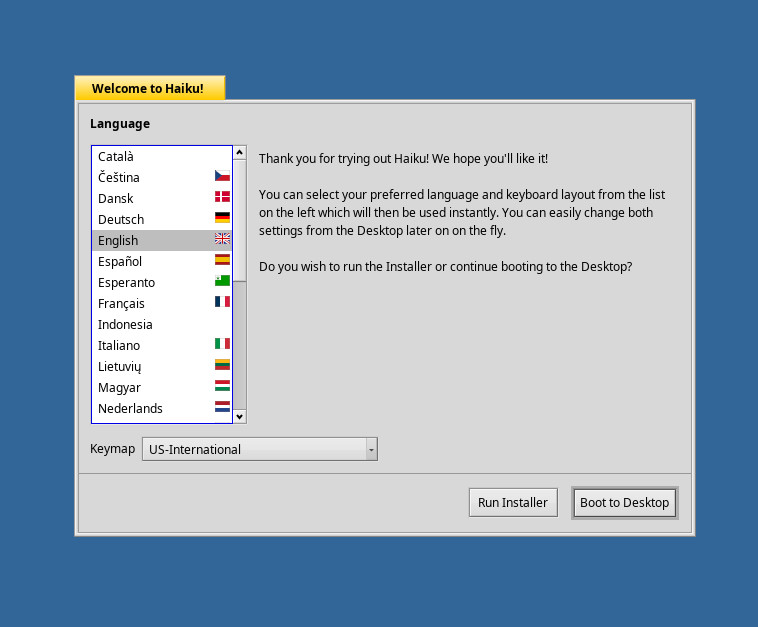

For my purposes, I installed Haiku as a VirtualBox virtual machine. I highly recommend going the same route, as you don’t want to have to worry about hardware detection. Creating Haiku as a virtual machine doesn’t require any special setup (beyond the standard). Once the live image has booted, you’ll be asked if you want to run the installer or boot directly to the desktop (Figure 1). Click Run Installer to begin the process.

The next window is nothing more than a warning that Haiku is beta software and informing you that the installer will make the Haiku partition bootable, but doesn’t integrate with your existing boot menu (in other words, it will not set up dual booting). In this window, click the Continue button.

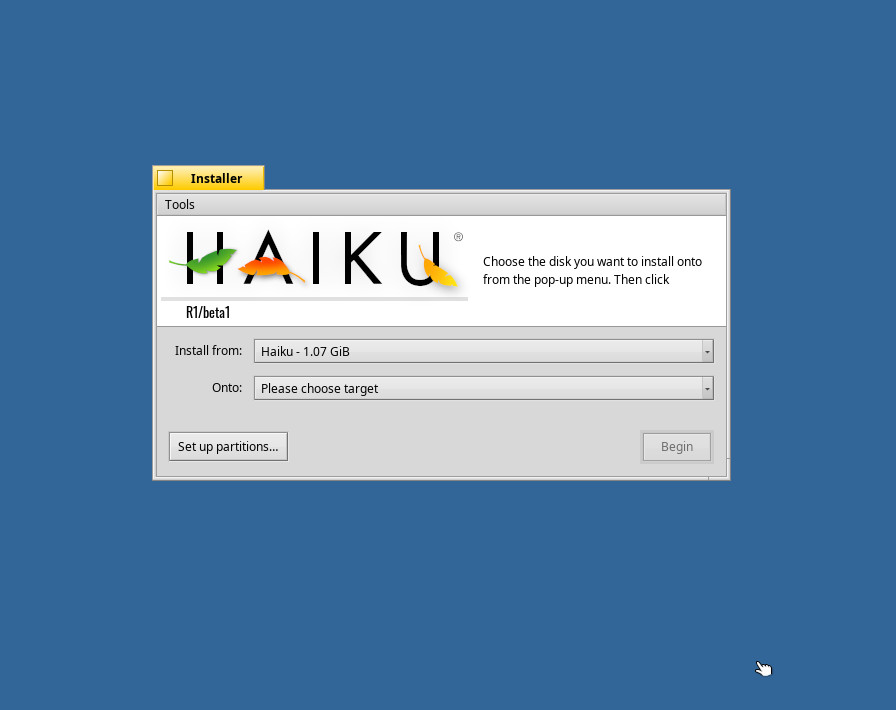

You will then be warned that no partitions have been found. Click the OK button, so you can create a partition table. In the remaining window (Figure 2), click the Set up partitions button.

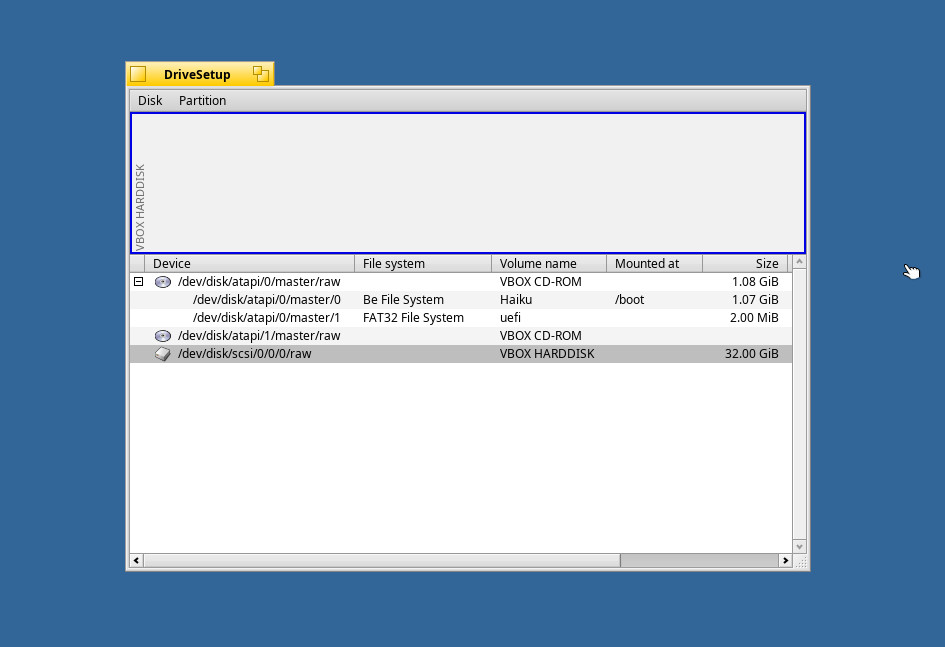

In the resulting window (Figure 3), select the partition to be used and then click Disk > Initialize > GUID Partition Map. You will be prompted to click Continue and then Write Changes.

Select the newly initialized partition and then click Partition > Format > Be File System. When prompted, click Continue. In the resulting window, leave everything default and click Initialize and then click Write changes.

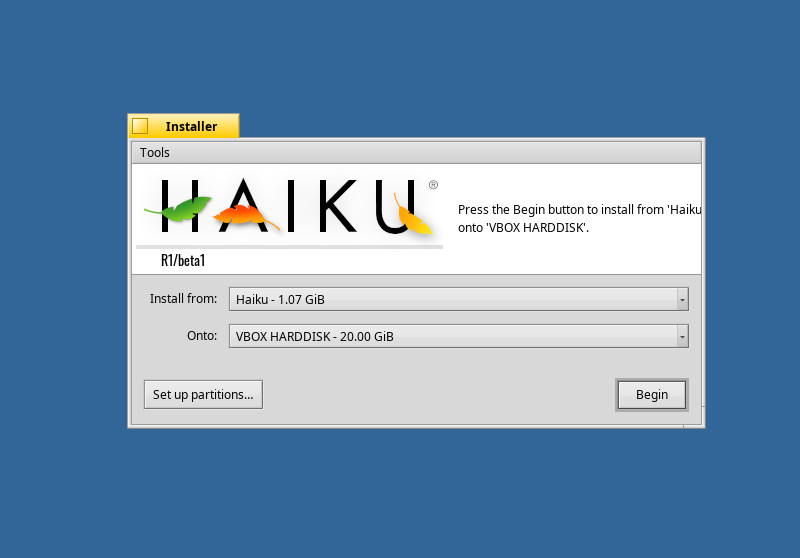

Close the DriveSetup window (click the square in the titlebar) to return to the Haiku Installer. You should now be able to select the newly formatted partition in the Onto drop-down (Figure 4).

After selecting the partition, click Begin and the installation will start. Don’t blink, as the entire installation takes less than 30 seconds. You read that correctly—the installation of Haiku takes less than 30 seconds. When it finishes, click Restart to boot your newly installed Haiku OS.

Usage

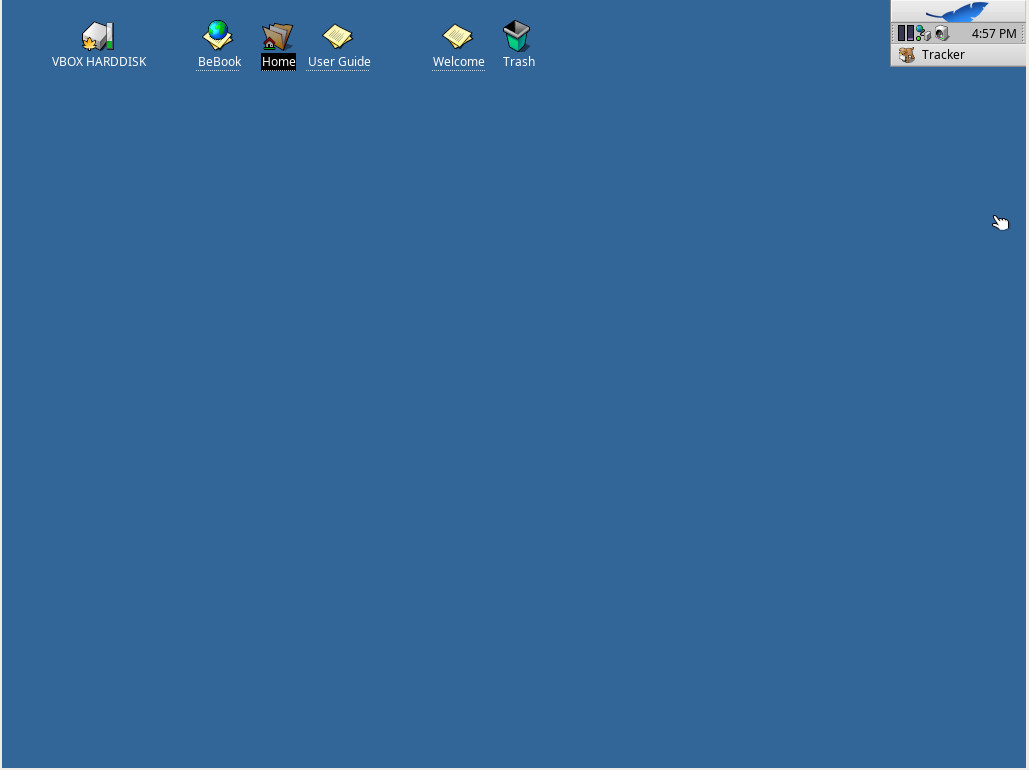

When Haiku boots, it’ll go directly to the desktop. There is no login screen (or even the means to log in). You’ll be greeted with a very simple desktop that includes a few clickable icons and what is called the Tracker(Figure 5).

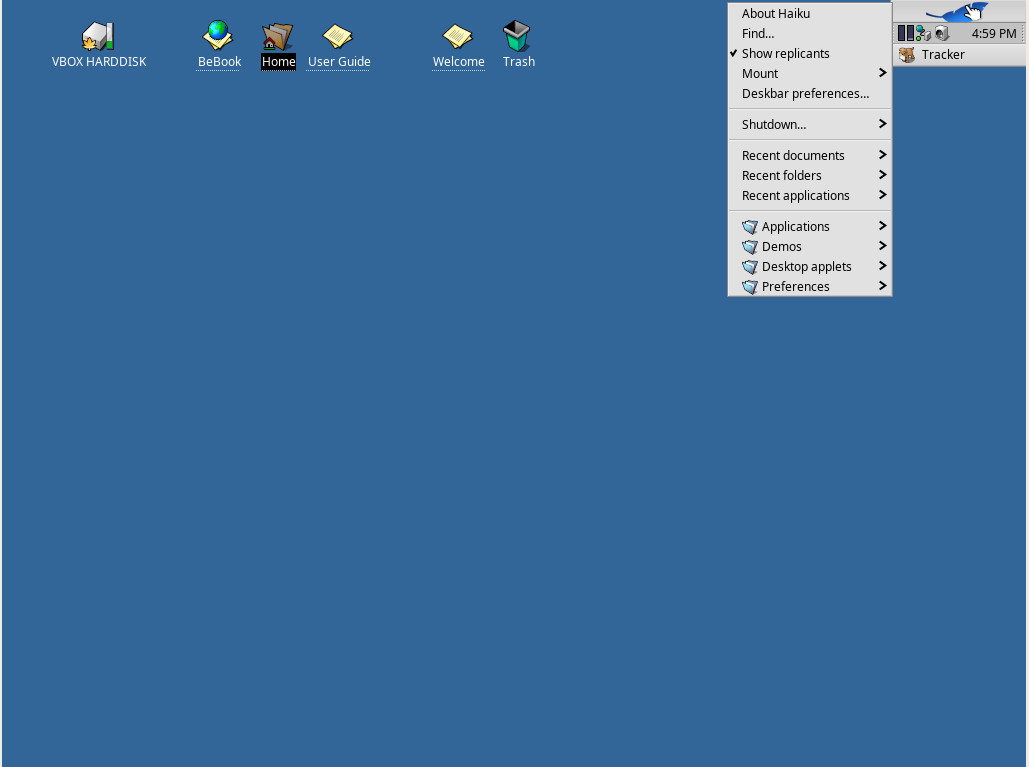

The Tracker includes any minimized application and a desktop menu that gives you access to all of the installed applications. Left click on the leaf icon in the Tracker to reveal the desktop menu (Figure 6).

From within the menu, click Applications and you’ll see all the available tools. In that menu you’ll find the likes of:

-

ActivityMonitor (Track system resources)

-

BePDF (PDF reader)

-

CodyCam (allows you to take pictures from a webcam)

-

DeskCalc (calculator)

-

Expander (unpack common archives)

-

HaikuDepot (app store)

-

Mail (email client)

-

MediaPlay (play audio files)

-

People (contact database)

-

PoorMan (simple web server)

-

SoftwareUpdater (update Haiku software)

-

StyledEdit (text editor)

-

Terminal (terminal emulator)

-

WebPositive (web browser)

You might find, in the HaikuDepot, a limited number of available applications. At first blush, what you won’t find are many productivity tools. Missing are office suites, image editors, and more. However, if you uncheck the “Show only featured packages”, you will find a large number of applications can be found. It would be my advice, that this feature be unchecked by default, otherwise users not in the know might seem to think Haiku has a very limited scope of applications available and that this beta version of Haiku is not a true desktop replacement, but a view into the work the developers have put into giving the now-defunct BoOS new life. Even with this tiny hiccup, this blast from the past is certainly worth checking out.

A positive step forward

Based on my experience with BeOS and the alpha of Haiku (all those years ago), the developers have taken a big, positive step forward. Hopefully, the next beta release won’t take as long and we might even see a final release in the coming years. Although Haiku won’t challenge the likes of Ubuntu, Mint, Arch, or Elementary OS, it could develop its own niche following. No matter its future, it’s good to see something new from the developers. Bravo to Haiku.

Your OS is prime

For a beta 2 release

Make it so, my friends.

The Top 13 Linux and Open Source Conferences in 2019

By the end of 2018, I’ll have spent nine weeks at one open source conference or another. Now, you don’t need to spend that much time on the road learning about Linux and open source software. But you can learn a lot and perhaps find a new job by cherry-picking from the many 2019 conferences you could attend.

Sometimes, a single how-to presentation can save you a week of work. A panel discussion can help you formulate an element of your corporate open source strategy. Sure, you can learn from booksor GitHub how-tos. But nothing is better than listening to the people who’ve done the work explain how they’ve solved the same problems you’re facing. With the way open source projects work, and the frequency with which they weave together to create great projects (such as cloud-native computing), you never know when a technology you may not have even heard of today can help you tomorrow.

So, I don’t know about you, but I’m already mapping which conferences I’m going to in 2019.

Read more at HPE

Tune Into Free Live Stream of Keynotes at Open Source Summit & ELC + OpenIoT Summit Europe, October 22-24!

Open Source Summit & ELC + OpenIoT Summit Europe is taking place in Edinburgh, UK next week, October 22-24, 2018. Can’t make it? You’ll be missed, but you don’t have to miss out on the action. Tune into the free livestream to catch all of the keynotes live from your desktop, tablet or phone! Sign up now >>

Hear from the leading technologists in open source! Get an inside scoop on:

- An update on the Linux kernel

- Diversity & inclusion to fuel open source growth

- How open source is changing banking

- How to build an open source culture within organizations

- Human rights & scientific collaboration

- The future of AI and Deep Learning

- The future of energy with open source

- The parallels between open source & video games

Sign up for free live stream now >>

Read more at The Linux Foundation

New Security Woes for Popular IoT Protocols

Researchers at Black Hat Europe will detail denial-of-service and other flaws in MQTT, CoAP machine-to-machine communications protocols that imperil industrial and other IoT networks online.

Security researcher Federico Maggi had been collecting data – some of it sensitive in nature – from hundreds of thousands of Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) servers he found sitting wide open on the public Internet via Shodan. “I would probe them and listen for 10 seconds or so, and just collect data from them,” he says.

He found data on sensors and other devices sitting in manufacturing and automotive networks, for instance, as well as typical consumer Internet of Things (IoT) gadgets.

The majority of data, Maggi says, came from consumer devices and sensors or was data he couldn’t identify. “There was a good amount of data from factories, and I was able to find data coming from pretty expensive industrial machines, including a robot,” he says.

MQTT and CoAP basically serve as the backbone of IoT and industrial IoT communications. As Maggi and Quarta discovered, the protocols often are deployed in devices insecurely, leaking sensitive information such as device details, user credentials, and network configuration information. The pair of researchers will present details and data from their findings in December at Black Hat Europe in London.

Read more at DarkReading

How to Use Git Version Control System in Linux [Comprehensive Guide]

Version Control (revision control or source control) is a way of recording changes to a file or collection of files over time so that you can recall specific versions later. A version control system (or VCS in short) is a tool that records changes to files on a filesystem.

There are many version control systems out there, but Git is currently the most popular and frequently used, especially for source code management. Version control can actually be used for nearly any type of file on a computer, not only source code.

Version control systems/tools offer several features that allow individuals or a group of people to:

- create versions of a project.

- track changes accurately and resolve conflicts.

- merge changes into a common version.

- rollback and undo changes to selected files or an entire project.

- access historical versions of a project to compare changes over time.

- see who last modified something that might be causing a problem.

- create a secure offsite backup of a project.

- use multiple machines to work on a single project and so much more.

A project under a version control system such as Git will have mainly three sections, namely:

- a repository: a database for recording the state of or changes to your project files. It contains all of the necessary Git metadata and objects for the new project. Note that this is normally what is copied when you clone a repository from another computer on a network or remote server.

- a working directory or area: stores a copy of the project files which you can work on (make additions, deletions and other modification actions).

- a staging area: a file (known as index under Git) within the Git directory, that stores information about changes, that you are ready to commit (save the state of a file or set of files) to the repository.

Read more at Tecmint

Raspbian Linux Distribution Updated, But with One Unexpected Omission

New distribution images for the Raspberry Pi’s Raspbian operating system appeared on their Download page a week or so ago. The dates of the new images are 2018-10-09 for the Raspbian-only version, and 2018-10-11 for the NOOBS (Raspbian and More) version.

In a nutshell, this release includes:

- a number of changes to the “first-run/startup wizard”, which is not surprising since that was just introduced in the previous release

- a couple of interesting changes which look to me like they are responses to potential security problems (password changes now work properly if the new password contains shell characters? Hmmm. I wonder if this came up simply because some users were having trouble changing passwords, or because some clever users found they could use this to attack the system? Oh, and who ever thought it was a good idea to display the WiFi password by default?)

- updates to the Linux kernel (4.14.71) and Pi firmware

- various other minor updates, bug fixes, new versions and such

- removed Mathematica

- Raspberry Pi PoE HAT support

Those last two are the ones that really produced some excitement in the Raspberry Pi community. Just look at that next to last one… so innocent looking… but then go and look at the discussion in the Pi Forums about it.

Read more at ZDNet

On the low adoption of automated testing in FOSS

For projects of any value and significance, having a comprehensive automated test suite is nowadays considered a standard software engineering practice. Why, then, don’t we see more prominent FOSS projects employing this practice?

By Alexandros Frantzis, Senior Software Engineer at Collabora.

A few times in the recent past I’ve been in the unfortunate position of using a prominent Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) program or library, and running into issues of such fundamental nature that made me wonder how those issues even made it into a release.

In all cases, the answer came quickly when I realized that, invariably, the project involved either didn’t have a test suite, or, if it did have one, it was not adequately comprehensive.

I am using the term comprehensive in a very practical, non extreme way. I understand that it’s often not feasible to test every possible scenario and interaction, but, at the very least, a decent test suite should ensure that under typical circumstances the code delivers all the functionality it promises to.

For projects of any value and significance, having such a comprehensive automated test suite is nowadays considered a standard software engineering practice. Why, then, don’t we see more prominent FOSS projects employing this practice, or, when they do, why is it often employed poorly?

In this post I will highlight some of the reasons that I believe play a role in the low adoption of proper automated testing in FOSS projects, and argue why these reasons may be misguided. I will focus on topics that are especially relevant from a FOSS perspective, omitting considerations, which, although important, are not particular to FOSS.

My hope is that by shedding some light on this topic, more FOSS projects will consider employing an automated test suite.

As you can imagine, I am a strong proponent of automating testing, but this doesn’t mean I consider it a silver bullet. I do believe, however, that it is an indispensable tool in the software engineering toolbox, which should only be forsaken after careful consideration.

1. Underestimating the cost of bugs

Most FOSS projects, at least those not supported by some commercial entity, don’t come with any warranty; it’s even stated in the various licenses! The lack of any formal obligations makes it relatively inexpensive, both in terms of time and money, to have the occasional bug in the codebase. This means that there are fewer incentives for the developer to spend extra resources to try to safeguard against bugs. When bugs come up, the developers can decide at their own leisure if and when to fix them and when to release the fixed version. Easy!

At first sight, this may seem like a reasonably pragmatic attitude to have. After all, if fixing bugs is so cheap, is it worth spending extra resources trying to prevent them?

Unfortunately, bugs are only cheap for the developer, not for the users who may depend on the project for important tasks. Users expect the code to work properly and can get frustrated or disappointed if this is not the case, regardless of whether there is any formal warranty. This is even more pronounced when security concerns are involved, for which the cost to users can be devastating.

Of course, lack of formal obligations doesn’t mean that there is no driver for quality in FOSS projects. On the contrary, there is an exceptionally strong driver: professional pride. In FOSS projects the developers are in the spotlight and no (decent) developer wants to be associated with a low quality, bug infested codebase. It’s just that, due to the mentality stated above, in many FOSS projects the trade-offs developers make seem to favor a reactive rather than proactive attitude.

2. Overtrusting code reviews

One of the development practices FOSS projects employ ardently is code reviews. Code reviews happen naturally in FOSS projects, even in small ones, since most contributors don’t have commit access to the code repository and the original author has to approve any contributions. In larger projects there are often more structured procedures which involve sending patches to a mailing list or to a dedicated reviewing platform. Unfortunately, in some projects the trust on code reviews is so great, that other practices, like automated testing, are forsaken.

There is no question that code reviews are one of the best ways to maintain and improve the quality of a codebase. They can help ensure that code is designed properly, it is aligned with the overall architecture and furthers the long term goals of the project. They also help catch bugs, but only some of them, some of the time!

The main problem with code reviews is that we, the reviewers, are only human. We humans are great at creative thought, but we are also great at overlooking things, occasionally filling in the gaps with our own unicorns-and-rainbows inspired reality. Another reason is that we tend to focus more on the code changes at a local level, and less on how the code changes affect the system as a whole. This is not an inherent problem with the process itself but rather a limitation of humans performing the process. When a codebase gets large enough, it’s difficult for our brains to keep all the possible states and code paths in mind and check them mentally, even in a codebase that is properly designed.

In theory, the problem of human limitations is offset by the open nature of the code. We even have the so called Linus’s law which states that “given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow”. Note the clever use of the indeterminate term “enough”. How many are enough? How about the qualitative aspects of the “eyeballs”?

The reality is that most contributions to big, successful FOSS projects are reviewed on average by a couple of people. Some projects are better, most are worse, but in no case does being FOSS magically lead to a large number of reviewers tirelessly checking code contributions. This limit in the number of reviewers also limits the extent to which code reviews can stand as the only process to ensure quality.

Continue reading on Collabora’s blog.

Understanding Linux Links: Part 1

Along with cp and mv, both of which we talked about at length in the previous installment of this series, links are another way of putting files and directories where you want them to be. The advantage is that links let you have one file or directory show up in several places at the same time.

As noted previously, at the physical disk level, things like files and directories don’t really exist. A filesystem conjures them up for our human convenience. But at the disk level, there is something called a partition table, which lives at the beginning of every partition, and then the data scattered over the rest of the disk.

Although there are different types of partition tables, the ones at the beginning of a partition containing your data will map where each directory and file starts and ends. The partition table acts like an index: When you load a file from your disk, your operating system looks up the entry on the table and the table says where the file starts on the disk and where it finishes. The disk header moves to the start point, reads the data until it reaches the end point and, hey presto: here’s your file.

Hard Links

A hard link is simply an entry in the partition table that points to an area on a disk that has already been assigned to a file. In other words, a hard link points to data that has already been indexed by another entry. Let’s see how this works.

Open a terminal, create a directory for tests and move into it:

mkdir test_dir cd test_dir

Create a file by touching it:

touch test.txt

For extra excitement (?), open test.txt in a text editor and add some a few words into it.

Now make a hard link by executing:

ln test.txt hardlink_test.txt

Run ls, and you’ll see your directory now contains two files… Or so it would seem. As you read before, really what you are seeing is two names for the exact same file: hardlink_test.txt contains the same content, has not filled any more space in the disk (try with a large file to test this), and shares the same inode as test.txt:

$ ls -li *test* 16515846 -rw-r--r-- 2 paul paul 14 oct 12 09:50 hardlink_test.txt 16515846 -rw-r--r-- 2 paul paul 14 oct 12 09:50 test.txt

ls‘s -i option shows the inode number of a file. The inode is the chunk of information in the partition table that contains the location of the file or directory on the disk, the last time it was modified, and other data. If two files share the same inode, they are, to all practical effects, the same file, regardless of where they are located in the directory tree.

Fluffy Links

Soft links, also known as symlinks, are different: a soft link is really an independent file, it has its own inode and its own little slot on the disk. But it only contains a snippet of data that points the operating system to another file or directory.

You can create a soft link using ln with the -s option:

ln -s test.txt softlink_test.txt

This will create the soft link softlink_test.txt to test.txt in the current directory.

By running ls -li again, you can see the difference between the two different kinds of links:

$ ls -li total 8 16515846 -rw-r--r-- 2 paul paul 14 oct 12 09:50 hardlink_test.txt 16515855 lrwxrwxrwx 1 paul paul 8 oct 12 09:50 softlink_test.txt -> test.txt 16515846 -rw-r--r-- 2 paul paul 14 oct 12 09:50 test.txt

hardlink_test.txt and test.txt contain some text and take up the same space *literally*. They also share the same inode number. Meanwhile, softlink_test.txt occupies much less and has a different inode number, marking it as a different file altogether. Using the ls‘s -l option also shows the file or directory your soft link points to.

Why Use Links?

They are good for applications that come with their own environment. It often happens that your Linux distro does not come with the latest version of an application you need. Take the case of the fabulous Blender 3D design software. Blender allows you to create 3D still images as well as animated films and who wouldn’t to have that on their machine? The problem is that the current version of Blender is always at least one version ahead of that found in any distribution.

Fortunately, Blender provides downloads that run out of the box. These packages come, apart from with the program itself, a complex framework of libraries and dependencies that Blender needs to work. All these bits and piece come within their own hierarchy of directories.

Every time you want to run Blender, you could cd into the folder you downloaded it to and run:

./blender

But that is inconvenient. It would be better if you could run the blender command from anywhere in your file system, as well as from your desktop command launchers.

The way to do that is to link the blender executable into a bin/ directory. On many systems, you can make the blender command available from anywhere in the file system by linking to it like this:

ln -s /path/to/blender_directory/blender /home/<username>/bin

Another case in which you will need links is for software that needs outdated libraries. If you list your /usr/lib directory with ls -l, you will see a lot of soft-linked files fly by. Take a closer look, and you will see that the links usually have similar names to the original files they are linking to. You may see libblah linking to libblah.so.2, and then, you may even notice that libblah.so.2 links in turn to libblah.so.2.1.0, the original file.

This is because applications often require older versions of alibrary than what is installed. The problem is that, even if the more modern versions are still compatible with the older versions (and usually they are), the program will bork if it doesn’t find the version it is looking for. To solve this problem distributions often create links so that the picky application believes it has found the older version, when, in reality, it has only found a link and ends up using the more up to date version of the library.

Somewhat related is what happens with programs you compile yourself from the source code. Programs you compile yourself often end up installed under /usr/local: the program itself ends up in /usr/local/bin and it looks for the libraries it needs / in the /usr/local/lib directory. But say that your new program needs libblah, but libblah lives in /usr/lib and that’s where all your other programs look for it. You can link it to /usr/local/lib by doing:

ln -s /usr/lib/libblah /usr/local/lib

Or, if you prefer, by cding into /usr/local/lib…

cd /usr/local/lib

… and then linking with:

ln -s ../lib/libblah

There are dozens more cases in which linking proves useful, and you will undoubtedly discover them as you become more proficient in using Linux, but these are the most common. Next time, we’ll look at some linking quirks you need to be aware of.

Learn more about Linux through the free “Introduction to Linux” course from The Linux Foundation and edX.

Take Our Cloud Providers Survey and Enter to Win a Maker Kit

Today’s most dynamic and innovative FOSS projects boast significant involvement by well-known cloud service and solution providers. We are launching a survey to better understand the perception of these solution providers by people engaging in open source communities.

Visible participation and application of corporate resources has been one of the key drivers of the success of open source software. However, some companies still face challenges:

-

Code consumption with minimal participation in leveraged projects, impacting ability to influence project direction

-

Hiring FOSS maintainers without a strategy or larger commitment to open source, impacting the ability to retain FOSS developers long-term

-

Compliance missteps and not adhering to FOSS license terms.

The experiences open source community members with different companies impact perception of those organizations among FOSS community participants. If companies want the trust of FOSS project participants, they must invest in building strategies, engaging communities, project participation and license compliance.

Cloud Solutions Providers FOSS Survey

The Linux Foundation has been commissioned to survey FOSS developers and users about their opinions, perceptions, and experiences with 6 top cloud solution and service providers that deploy open source software. The survey examines respondents’ views of reputation, levels of project engagement, contribution, community citizenship and project sponsorship by six major cloud product and services providers.

By completing this survey, you will be eligible for a drawing for one of ten Maker Hardware kits, complete with case, cables, power supply, and other accessories. The survey will remain open until 12 a.m. EST on November 18, 2018.

Drawing Rules

-

At the end of survey period, The Linux Foundation (LF) will randomly choose ten (10) respondents to receive a Maker hardware kit (“prize”).

-

Participants are only eligible to win one prize for this drawing and after winning a first prize will not be entered into any additional prize drawings for this promotion.

-

You must be 18 years or older to participate. Employees, vendors and contractors of The Linux Foundation and their families are not eligible, but LF project participants and employees of member companies are encouraged to complete the survey and enter the drawing

-

To enter the drawing, you must only complete the contact info (name, email, etc.). Completing the contact info will constitute an “entry”. Any participant submitting multiple entries may be disqualified without notice. The Linux Foundation reserves the right to disqualify any participants if for any reason inaccurate or incomplete information is suspected.

-

There is no cash equivalent and no person other than the winning person may take delivery of the prize(s). The prize may not be exchanged for cash.

-

The deadline for participation in the drawing is open until 12 a.m. EST on December 10, 2018. Any participants completing a survey after the deadline will not be entered into the drawing. The survey may remain open to participate beyond the drawing deadline.

-

Entries will be pooled together and a winner will be randomly selected. The winner will be notified via email. The winner’s name, city, and state of residence will be directly contacted and may be posted on our respective social media/marketing outlets (Linux.com, Twitter, Facebook, Google+, etc.). Winners have 30 days to respond to our contact or a new drawing for the prize will be made.