Interested in learning more about Linux administration? Explore these Linux training courses.

Learn how to kill errant processes in this tutorial from our archives.

Picture this: You’ve launched an application (be it from your favorite desktop menu or from the command line) and you start using that launched app, only to have it lock up on you, stop performing, or unexpectedly die. You try to run the app again, but it turns out the original never truly shut down completely.

What do you do? You kill the process. But how? Believe it or not, your best bet most often lies within the command line. Thankfully, Linux has every tool necessary to empower you, the user, to kill an errant process. However, before you immediately launch that command to kill the process, you first have to know what the process is. How do you take care of this layered task? It’s actually quite simple…once you know the tools at your disposal.

Let me introduce you to said tools.

The steps I’m going to outline will work on almost every Linux distribution, whether it is a desktop or a server. I will be dealing strictly with the command line, so open up your terminal and prepare to type.

Locating the process

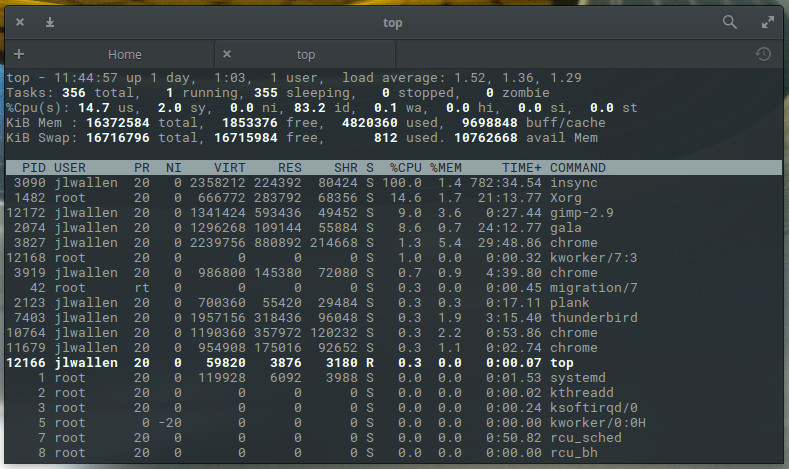

The first step in killing the unresponsive process is locating it. There are two commands I use to locate a process: top and ps. Top is a tool every administrator should get to know. With top, you get a full listing of currently running process. From the command line, issue top to see a list of your running processes (Figure 1).

From this list you will see some rather important information. Say, for example, Chrome has become unresponsive. According to our top display, we can discern there are four instances of chrome running with Process IDs (PID) 3827, 3919, 10764, and 11679. This information will be important to have with one particular method of killing the process.

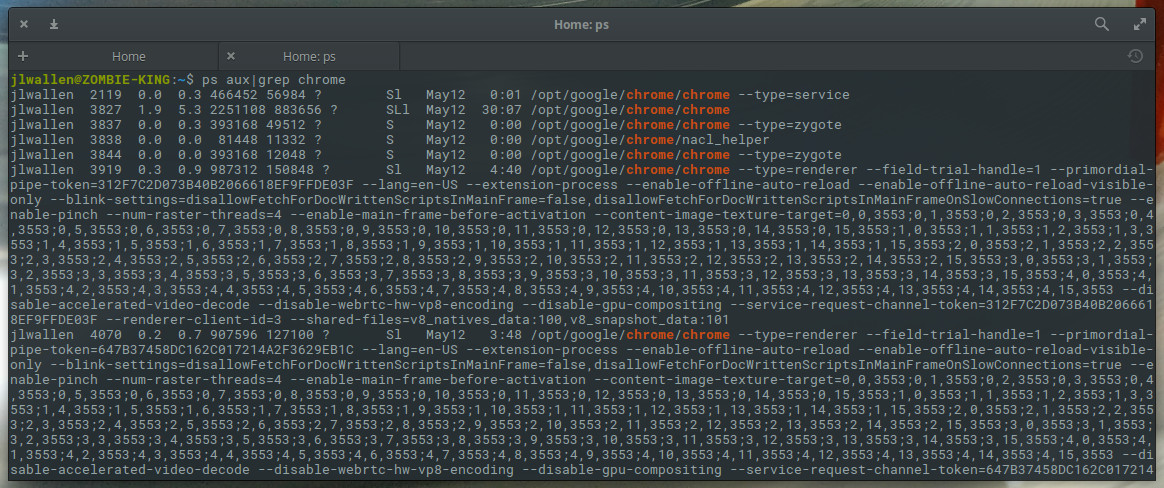

Although top is incredibly handy, it’s not always the most efficient means of getting the information you need. Let’s say you know the Chrome process is what you need to kill, and you don’t want to have to glance through the real-time information offered by top. For that, you can make use of the ps command and filter the output through grep. The ps command reports a snapshot of a current process and grep prints lines matching a pattern. The reason why we filter ps through grep is simple: If you issue the ps command by itself, you will get a snapshot listing of all current processes. We only want the listing associated with Chrome. So this command would look like:

ps aux | grep chrome

The aux options are as follows:

-

a = show processes for all users

-

u = display the process’s user/owner

-

x = also show processes not attached to a terminal

The x option is important when you’re hunting for information regarding a graphical application.

When you issue the command above, you’ll be given more information than you need (Figure 2) for the killing of a process, but it is sometimes more efficient than using top.

Killing the process

Now we come to the task of killing the process. We have two pieces of information that will help us kill the errant process:

-

Process name

-

Process ID

Which you use will determine the command used for termination. There are two commands used to kill a process:

-

kill – Kill a process by ID

-

killall – Kill a process by name

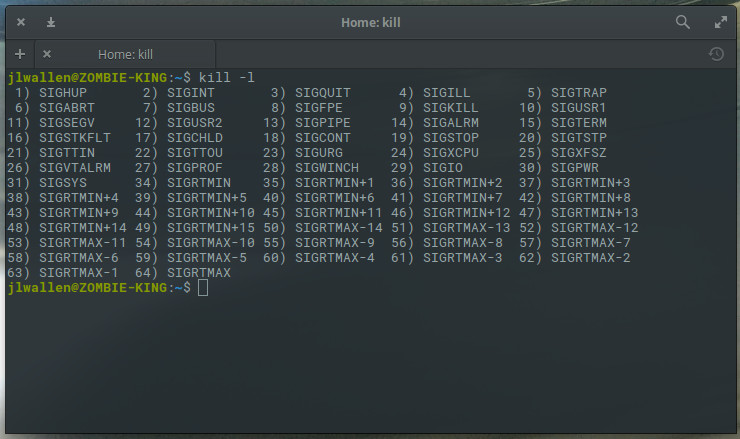

There are also different signals that can be sent to both kill commands. What signal you send will be determined by what results you want from the kill command. For instance, you can send the HUP (hang up) signal to the kill command, which will effectively restart the process. This is always a wise choice when you need the process to immediately restart (such as in the case of a daemon). You can get a list of all the signals that can be sent to the kill command by issuing kill -l. You’ll find quite a large number of signals (Figure 3).

The most common kill signals are:

|

Signal Name |

Single Value |

Effect |

|

SIGHUP |

1 |

Hangup |

|

SIGINT |

2 |

Interrupt from keyboard |

|

SIGKILL |

9 |

Kill signal |

|

SIGTERM |

15 |

Termination signal |

|

SIGSTOP |

17, 19, 23 |

Stop the process |

What’s nice about this is that you can use the Signal Value in place of the Signal Name. So you don’t have to memorize all of the names of the various signals.

So, let’s now use the kill command to kill our instance of chrome. The structure for this command would be:

kill SIGNAL PID

Where SIGNAL is the signal to be sent and PID is the Process ID to be killed. We already know, from our ps command that the IDs we want to kill are 3827, 3919, 10764, and 11679. So to send the kill signal, we’d issue the commands:

kill -9 3827 kill -9 3919 kill -9 10764 kill -9 11679

Once we’ve issued the above commands, all of the chrome processes will have been successfully killed.

Let’s take the easy route! If we already know the process we want to kill is named chrome, we can make use of the killall command and send the same signal the process like so:

killall -9 chrome

The only caveat to the above command is that it may not catch all of the running chrome processes. If, after running the above command, you issue the ps aux|grep chrome command and see remaining processes running, your best bet is to go back to the kill command and send signal 9 to terminate the process by PID.

Ending processes made easy

As you can see, killing errant processes isn’t nearly as challenging as you might have thought. When I wind up with a stubborn process, I tend to start off with the killall command as it is the most efficient route to termination. However, when you wind up with a really feisty process, the kill command is the way to go.

Learn more about Linux through the free “Introduction to Linux” course from The Linux Foundation and edX.