At Embedded Linux Conference Europe, Satish Chetty explained his work on a Linux-driven sensor buoy deployed to monitor sea ice off the north coast of Alaska.

At Embedded Linux Conference Europe, Satish Chetty explained his work on a Linux-driven sensor buoy deployed to monitor sea ice off the north coast of Alaska.

Konsulko’s Matt Porter and Scott Murray ran through the major components of the AGL’s Unified Code Base at Embedded Linux Conference Europe.

In this talk from Xen Summit, Florian Schmidt, a researcher at NEC Europe, describes uniprof, a unikernel performance profiler that can also be used for debugging.

With all the attention you are seeing on Linux and its use on the Internet and in devices like Arduino, Beagle, and Raspberry Pi boards and more, perhaps you are thinking it’s time to try it out. This series will help you successfully make the transition to Linux. If you missed the earlier articles in the series, you can find them here:

Part 2 – Disks, Files, and Filesystems

Part 3 – Graphical Environments

To get new software on your computer, the typical approach used to be to get a software product from a vendor and then run an install program. The software product, in the past, would come on physical media like a CD-ROM or DVD. Now we often download the software product from the Internet instead.

With Linux, software is installed more like it is on your smartphone. Just like going to your phone’s app store, on Linux there is a central repository of open source software tools and programs. Just about any program you might want will be in a list of available packages that you can install.

There isn’t a separate install program that you run for each program. Instead you use the package management tools that come with your distribution of Linux. (Remember a Linux distribution is the Linux you install such as Ubuntu, Fedora, Debian, etc.) Each distribution has its own centralized place on the Internet (called a repository) where they store thousands of pre-built applications for you to install.

You may note that there are a few exceptions to how software is installed on Linux. Sometimes, you will still need to go to a vendor to get their software as the program doesn’t exist in your distribution’s central repository. This typically is the case when the software isn’t open source and/or not free.

Also keep in mind that if you end up wanting to install a program that is not in your distribution’s repositories, things aren’t so simple, even if you are installing free and open source programs. This post doesn’t get into these more complicated scenarios, and it’s best to follow online directions.

With all the Linux packaging systems and tools out there, it may be confusing to know what’s going on. This article should help clear up a few things.

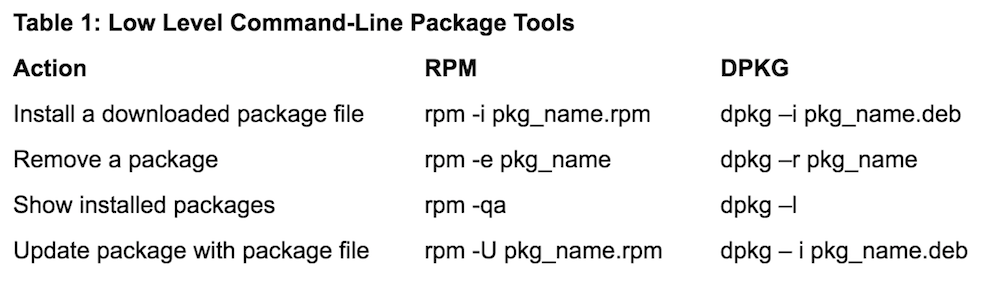

Several packaging systems to manage, install, and remove software compete for use in Linux distributions. The folks behind each distribution choose a package management system to use. Red Hat, Fedora, CentOS, Scientific Linux, SUSE, and others use the Red Hat Package Manager (RPM). Debian, Ubuntu, Linux Mint, and more use the Debian package system, or DPKG for short. Other package systems exist as well, while RPM and DPKG are the most common.

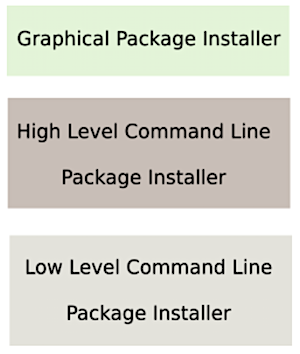

Regardless of the package manager you are using, they typically come with a set of tools that are layered on top of one another (Figure 1). At the lowest level is a command-line tool that lets you do anything and everything related to installed software. You can list installed programs, remove programs, install package files, and more.

This low-level tool isn’t always the most convenient to use, so typically there is a command line tool that will find the package in the distribution’s central repositories and download and install it along with any dependencies using a single command. Finally, there is usually a graphical application that lets you select what you want with a mouse and click an ‘install” button.

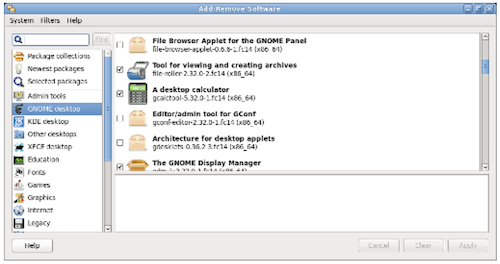

For Red Hat based distributions, which includes Fedora, CentOS, Scientific Linux, and more, the low-level tool is rpm. The high-level tool is called dnf (or yum on older systems). And the graphical installer is called PackageKit (Figure 2) and may appear as “Add/Remove Software” under System Administration.

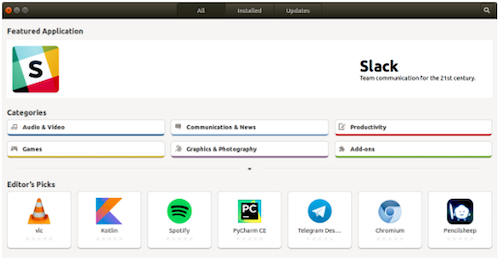

For Debian based distributions, which includes Debian, Ubuntu, Linux Mint, Elementary OS, and more, the low-level, command-line tool is dpkg. The high-level tool is called apt. The graphical tool to manage installed software on Ubuntu is Ubuntu Software (Figure 3). For Debian and Linux Mint, the graphical tool is called Synaptic, which can also be installed on Ubuntu.

You can also install a text-based graphical tool on Debian related distributions called aptitude. It is more powerful than Synaptic, and works even if you only have access to the command line. You can try that one if you want access to all the bells and whistles, though with more options, it is more complicated to use than Synaptic. Other distributions may have their own unique tools.

Online instructions for installing software on Linux usually describe commands to type in the command line. The instructions are usually easier to understand and can be followed without making a mistake by copying and pasting the command into your command line window. This is opposed to following instructions like, “open this menu, select this program, enter in this search pattern, click this tab, select this program, and click this button,” which often get lost in translation.

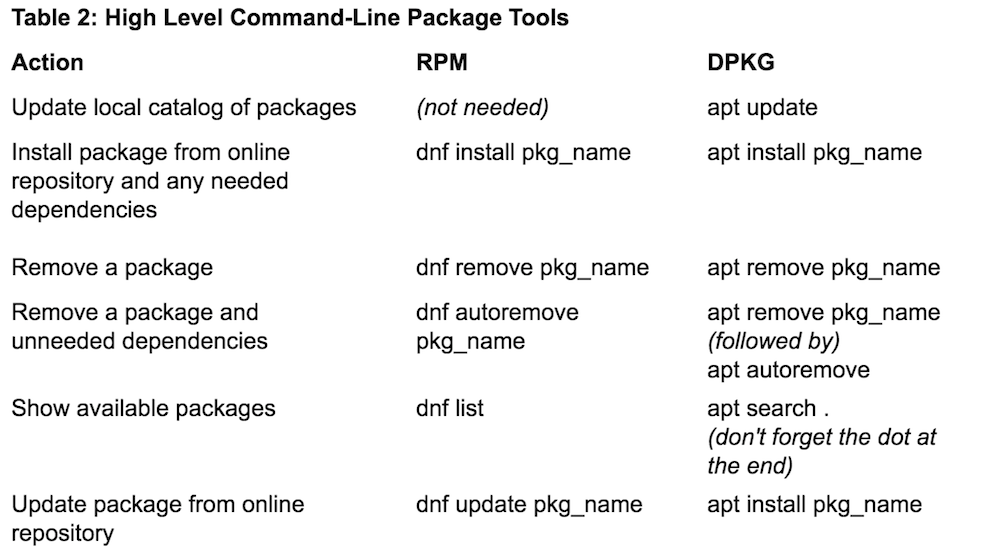

Sometimes the Linux installation you are using doesn’t have a graphical environment, so it’s good to be familiar with installing software packages from the command line. Tables 1 and 2 a few common operations and their associated commands for both RPM and DPKG based systems.

Note that SUSE, which uses RPM like Redhat and Fedora, doesn’t have dnf or yum. Instead, it uses a program called zypper for the high-level, command-line tool. Other distributions may have different tools as well, such as, pacman on Arch Linux or emerge on Gentoo. There are many package tools out there, so you may need to look up what works on your distribution.

These tips should give you a much better idea on how to install programs on your new Linux installation and a better idea how the various package methods on your Linux installation relate to one another.

Learn more about Linux through the free “Introduction to Linux” course from The Linux Foundation and edX.

Ask a person if he or she is a racist and the answer is almost always no. Ask a developer if they consider ethical considerations when writing code and only six percent say no. If everyone acted the way they self-report, then there would be peace and love throughout the world.

Based on over a hundred thousand respondents, StackOverflow’s Developer Survey 2018 presents a more complicated reality. If they were asked to write code for an unethical purpose, 59 percent would say no, but another 37 percent of developers were non-committal about whether they would comply. In another question, only about 5 percent said they definitely not report unethical problems with code. But sounding the alarm is about as far as most people will go.

Read more at The New Stack

The latest enhancements to the DRM subsystem have made mainline Linux much more attractive, making drivers easier to write, applications portable, and a much more friendly and collaborative community than we’ve ever had.

By Daniel Stone, Graphics Lead at Collabora.

Over the past couple of years, Linux’s low-level graphics infrastructure has undergone a quiet revolution. Since experimental core support for the atomic modesetting framework landed a couple of years ago, the DRM subsystem in the kernel has seen roughly 300,000 lines of code changed and 300,000 new lines added, when the new AMD driver (~2.5m lines) is excluded. Lately Weston has undergone the same revolution, albeit on a much smaller scale.

Daniel Vetter’s excellent two-part series on LWN covers the details quite well, but in short atomic has two headline features. The first is better display control: by grouping all configuration changes together, it is possible to change display modes more quickly and more reliably, especially if you have multiple monitors. The second is that it allows userspace to finally use overlay planes in the display controller for composition, bypassing the GPU.

A third, less heralded, feature is that the atomic core standardises user-visible behaviour. Before atomic, drivers had very wide latitude to implement whatever user-facing behaviour they liked. As a result, each chipset had its own kernel driver and its own X11 driver as well. With the rewrite of the core, backed up by a comprehensive test suite, we no longer need hardware-specific drivers to take full advantage of hardware features. With the substantial rework of Weston’s DRM backend, we can now take full advantage of these. Using atomic gives us a smoother user experience, with better performance and using less power, whilst still being completely hardware-agnostic.

This has made mainline Linux much more attractive: the exact same generic codebases of GNOME and Weston that I’m using to write this blog post on an Intel laptop run equally well on AMD workstations, low-power NXP boards destined for in-flight entertainment, and high-end Renesas SoCs which might well be in your car. Now that the drivers are easy to write, and applications are portable, we’ve seen over ten new DRM drivers merged to the upstream kernel since atomic modesetting was merged. These drivers are landing in a much more friendly and collaborative community than we’ve ever had.

If you’ve implemented, or are implementing, a DevSecOps program, we’ve come up with several questions to consider below. By posing these questions, we hope to help spur new ideas and help identify areas for improvement.

Is My Application (or Microservice) Leaking Data?

While microservices have helped many organizations increase their development velocity and efficiency, they also make understanding data flows across an application more complex. As developers become more focused on the microservice they work on, their overall view becomes more siloed. Developers simply don’t understand how every microservices handles every type of data and, as a result, its becoming increasingly common for unencrypted critical data to be leaked to 3rd party databases and other services like code repositories, logging, analytics.

Read more at Security Boulevard

The last command provides an easy way to review recent logins on a Linux system. It also has some useful options –- such as looking for logins for one particular user or looking for logins in an older wtmp file.

The last command with no arguments will easily show you all recent logins. It pulls the information from the current wtmp (/var/log/wtmp) file and shows the logins in reverse sequential order (newest first).

Read more at Network World

In summer 2017, I wrote two how-to articles about using Ansible. After the first article, I planned to show examples of the copy, systemd, service, apt, yum, virt, and usermodules. But I decided to tighten the scope of the second part to focus on using the yum and user modules. I explained how to set up a basic Git SSH server and explored the command, file, authorized_keys, yum, and user modules. In this third article, I’ll go into using Ansible for system monitoring with the Prometheus open source monitoring solution.

If you followed along with those first two articles, you should have:

git user, which is used to check code in and out of the Git SSH serverRead more at OpenSource.com

If you’re a Linux administrator and looking to lock down your Linux servers and desktops as tight as possible, you owe it to yourself to make use of two-factor authentication. This should be considered as “no-brainer” as they come. Why? Because by adding two-factor authentication, it becomes exponentially more difficult for malicious users to gain access to your machines. With Linux, it is possible to set up a machine so that you cannot log into the console or desktop or by way of secure shell, without having the two-factor authentication code associated with that machine.

I’m going to walk you through the process of setting this up on Ubuntu Server 16.04. If you’ve attempted this process before, know that the steps have changed and the previously detailed method no longer works.

Read more at TechRepublic