BIND (Berkeley Internet Name Domain) is the most used DNS software over the Internet. The BIND package is available for all Linux distributions, which makes the installation simple and straightforward. In today’s article we will show you how to install, configure and administer BIND 9 as a private DNS server on a Ubuntu 16.04 VPS, in few steps.

Requirements:

- Two servers (ns1 and ns2) connected to a private network

- In this tutorial we will use the 10.20.0.0/16 subnet

- DNS clients that will connect to your DNS servers

How to Set Up Private DNS Servers with BIND on Ubuntu 16.04

BIND (Berkeley Internet Name Domain) is the most used DNS software over the Internet. The BIND package is available for all Linux distributions, which makes the installation simple and straightforward. In today’s article we will show you how to install, configure and administer BIND 9 as a private DNS server on a Ubuntu 16.04 VPS, in few steps.

Requirements:

- Two servers (ns1 and ns2) connected to a private network

- In this tutorial we will use the 10.20.0.0/16 subnet

- DNS clients that will connect to your DNS servers

1. Update both servers

Begin by updating the packages on both servers:

# sudo apt-get update

2. Install BIND on both servers

# sudo apt-get install bind9 bind9utils

3. Set BIND to IPv4 mode

Set BIND to IPv4 mode, we will do that by editing the “/etc/default/bind9” file and adding “-4” to the OPTIONS variable:

# sudo nano /etc/default/bind9

The edited file should look something like this:

# run resolvconf? RESOLVCONF=no # startup options for the server OPTIONS="-4 -u bind"

Now let’s configure ns1, our primary DNS server.

4. Configuring the Primary DNS Server

Edit the named.conf.options file:

# sudo nano /etc/bind/named.conf.options

On top of the options block, add a new block called trusted.This list will allow the clients specified in it to send recursive DNS queries to our primary server:

acl "trusted" {

10.20.30.13;

10.20.30.14;

10.20.55.154;

10.20.55.155;

};

5. Enable recursive queries on our ns1 server, and have the server listen on our private network

Then we will add a couple of configuration settings to enable recursive queries on our ns1 server and to have the server listen on our private network, add the configuration settings under the directory “/var/cache/bind” directive like in the example below:

options {

directory "/var/cache/bind";

recursion yes;

allow-recursion { trusted; };

listen-on { 10.20.30.13; };

allow-transfer { none; };

forwarders {

8.8.8.8;

8.8.4.4;

};

};

If the “listen-on-v6” directive is present in the named.conf.options file, delete it as we want BIND to listen only on IPv4.

Now on ns1, open the named.conf.local file for editing:

# sudo nano /etc/bind/named.conf.local

Here we are going to add the forward zone:

zone "test.example.com" {

type master;

file "/etc/bind/zones/db.test.example.com";

allow-transfer { 10.20.30.14; };

};

Our private subnet is 10.20.0.0/16, so we are going to add the reverse zone with the following lines:

zone "20.10.in-addr.arpa" {

type master;

file "/etc/bind/zones/db.10.20";

allow-transfer { 10.20.30.14; };

};

If your servers are in multiple private subnets in the same physical location, you need to specify a zone and create a separate zone file for each subnet.

6. Creating the Forward Zone File

Now we’ll create the directory where we will store our zone files in:

# sudo mkdir /etc/bind/zones

We will use the sample db.local file to make our forward zone file, let’s copy the file first:

# cd /etc/bind/zones # sudo cp ../db.local ./db.test.example.com

Now edit the forward zone file we just copied:

# sudo nano /etc/bind/zones/db.test.example.com

It should look something like the example below:

$TTL 604800

@ IN SOA localhost. root.localhost. (

2 ; Serial

604800 ; Refresh

86400 ; Retry

2419200 ; Expire

604800 ) ; Negative Cache TTL

;

@ IN NS localhost. ; delete this

@ IN A 127.0.0.1 ; delete this

@ IN AAAA ::1 ; delete this

Now let’s edit the SOA record. Replace localhost with your ns1 server’s FQDN, then replace “root.localhost” with “admin.test.example.com”.Every time you edit the zone file, increment the serial value before you restart named otherwise BIND won’t apply the change to the zone, we will increment the value to “3”, it should look something like this:

@ IN SOA ns1.test.example.com. admin.test.example.com. (

3 ; Serial

Then delete the last three records that are marked with “delete this” after the SOA record.

Add the nameserver records at the end of the file:

; name servers - NS records

IN NS ns1.test.example.com.

IN NS ns2.test.example.com.

After that add the A records for the hosts that need to be in this zone. That means any server whose name we want to end with “.test.example.com”:

; name servers - A records ns1.test.example.com. IN A 10.20.30.13 ns2.test.example.com. IN A 10.20.30.14 ; 10.20.0.0/16 - A records host1.test.example.com. IN A 10.20.55.154 host2.test.example.com. IN A 10.20.55.155

The db.test.example.com file should look something like the following:

$TTL 604800

@ IN SOA ns1.test.example.com. admin.test.example.com. (

3 ; Serial

604800 ; Refresh

86400 ; Retry

2419200 ; Expire

604800 ) ; Negative Cache TTL

;

; name servers - NS records

IN NS ns1.test.example.com.

IN NS ns2.test.example.com.

; name servers - A records

ns1.test.example.com. IN A 10.20.30.13

ns2.test.example.com. IN A 10.20.30.14

; 10.20.0.0/16 - A records

host1.test.example.com. IN A 10.20.55.154

host2.test.example.com. IN A 10.20.55.155

7. Creating the Reverse Zone File

We specify the PTR records for reverse DNS lookups in the reverse zone files. When the DNS server receives a PTR lookup query for an example for IP: “10.20.55.154”, it will check the reverse zone file to retrieve the FQDN of the IP address, in our case that would be “host1.test.example.com”.

We will create a reverse zone file for every single reverse zone specified in the named.conf.local file we created on ns1. We will use the sample db.127 zone file to create our reverse zone file:

# cd /etc/bind/zones # sudo cp ../db.127 ./db.10.20

Edit the reverse zone file so it matches the reverse zone defined in named.conf.local:

# sudo nano /etc/bind/zones/db.10.20

The original file should look something like the following:

$TTL 604800

@ IN SOA localhost. root.localhost. (

1 ; Serial

604800 ; Refresh

86400 ; Retry

2419200 ; Expire

604800 ) ; Negative Cache TTL

;

@ IN NS localhost. ; delete this

1.0.0 IN PTR localhost. ; delete this

You should modify the SOA record and increment the serial value. It should look something like this:

@ IN SOA ns1.test.example.com. admin.test.example.com. (

3 ; Serial

Then delete the last three records that are marked with “delete this” after the SOA record.

Add the nameserver records at the end of the file:

; name servers - NS records

IN NS ns1.test.example.com.

IN NS ns2.test.example.com.

Now add the PTR records for all hosts that are on the same subnet in the zone file you created. This consists of our hosts that are on the 10.20.0.0/16 subnet. In the first column we reverse the order of the last two octets from the IP address of the host we want to add:

; PTR Records 13.30 IN PTR ns1.test.example.com. ; 10.20.30.13 14.30 IN PTR ns2.test.example.com. ; 10.20.30.14 154.55 IN PTR host1.test.example.com. ; 10.20.55.154 155.55 IN PTR host2.test.example.com. ; 10.20.55.155

Save and exit the reverse zone file.

The “/etc/bind/zones/db.10.20” reverse zone file should look something like this:

$TTL 604800

@ IN SOA test.example.com. admin.test.example.com. (

3 ; Serial

604800 ; Refresh

86400 ; Retry

2419200 ; Expire

604800 ) ; Negative Cache TTL

; name servers

IN NS ns1.test.example.com.

IN NS ns2.test.example.com.

; PTR Records

13.30 IN PTR ns1.test.example.com. ; 10.20.30.13

14.30 IN PTR ns2.test.example.com. ; 10.20.30.14

154.55 IN PTR host1.test.example.com. ; 10.20.55.154

155.55 IN PTR host2.test.example.com. ; 10.20.55.155

8. Check the Configuration Files

Use the following command to check the configuration syntax of all the named.conf files that we configured:

# sudo named-checkconf

If your configuration files don’t have any syntax problems, the output will not contain any error messages. However if you do have problems with your configuration files, compare the settings in the “Configuring the Primary DNS Server” section with the files you have errors in and make the correct adjustment, then you can try executing the named-checkconf command again.

The named-checkzone can be used to check the proper configuration of your zone files.You can use the following command to check the forward zone “test.example.com”:

# sudo named-checkzone test.example.com db.test.example.com

And if you want to check the reverse zone configuration, execute the following command:

# sudo named-checkzone 20.10.in-addr.arpa /etc/bind/zones/db.10.20

Once you have properly configured all the configuration and zone files, restart the BIND service:

# sudo service bind9 restart

9. Configuring the Secondary DNS Server

Setting up a secondary DNS server is always a good idea as it will serve as a failover and will respond to queries if the primary server is unresponsive.

On ns2, edit the named.conf.options file:

# sudo nano /etc/bind/named.conf.options

At the top of the file, add the ACL with the private IP addresses for all your trusted servers:

acl "trusted" {

10.20.30.13;

10.20.30.14;

10.128.100.101;

10.128.200.102;

};

Just like in the named.conf.options file for ns2, add the following lines under the directory “/var/cache/bind” directive:

recursion yes;

allow-recursion { trusted; };

listen-on { 10.20.30.13; };

allow-transfer { none; };

forwarders {

8.8.8.8;

8.8.4.4;

};

Save and exit the file.

Now open the named.conf.local file for editing:

# sudo nano /etc/bind/named.conf.local

Now we should specify slave zones that match the master zones on the ns1 DNS server. The masters directive should be set to the ns1 DNS server’s private IP address:

zone "test.example.com" {

type slave;

file "slaves/db.test.example.com";

masters { 10.20.30.13; };

};

zone "20.10.in-addr.arpa" {

type slave;

file "slaves/db.10.20";

masters { 10.20.30.13; };

};

Now save and exit the file.

Use the following command to check the syntax of the configuration files:

# sudo named-checkconf

Then restart the BIND service:

# sudo service bind9 restart

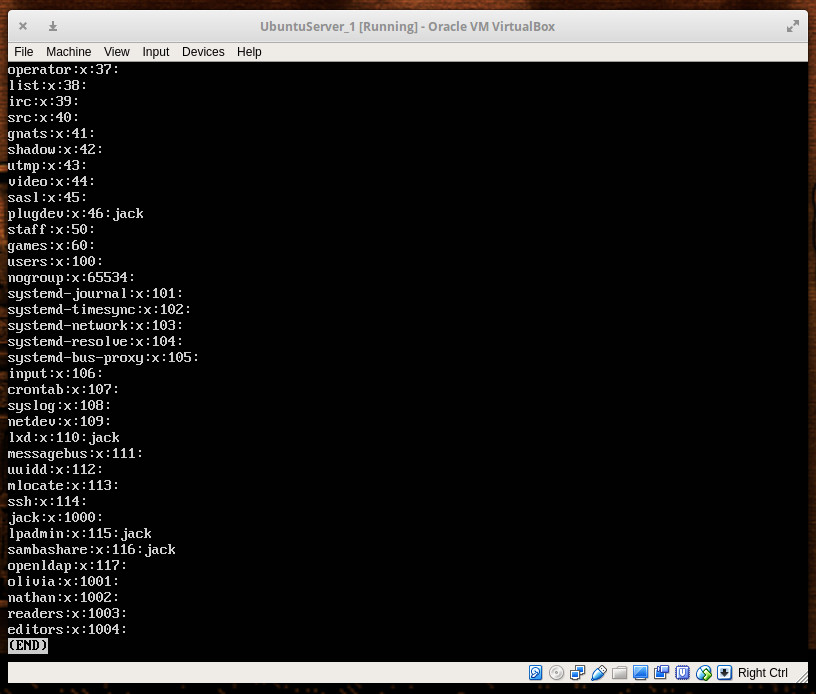

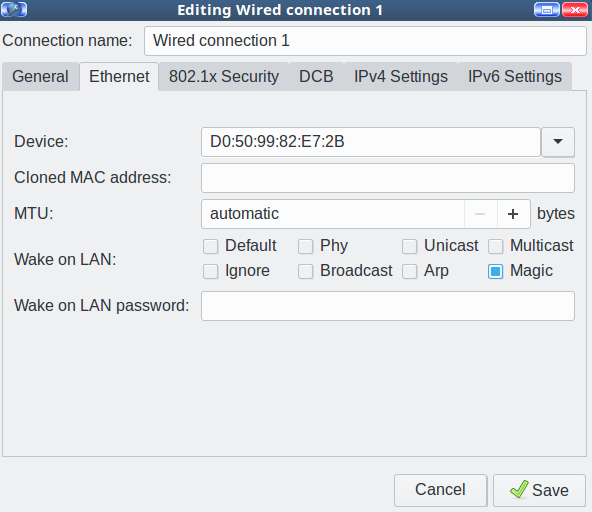

10. Configure the DNS Clients

We will now configure the hosts in our 10.20.0.0/16 subnet to use the ns1 and ns2 servers as their primary and secondary DNS servers. This greatly depends on the OS the hosts are running but for most Linux distributions the settings that need to be changed reside in the /etc/resolv.conf file.

Generally on the Ubuntu, Debian and CentOS distributions just edit the /etc/resolv.conf file, execute the following command as root:

# nano /etc/resolv.conf

Then replace the existing nameservers with:

nameserver 10.20.30.13 #ns1 nameserver 10.20.30.14 #ns2

Now save and exit the file and your client should be configured to use the ns1 and ns2 nameservers.

Then test if your clients can send queries to the DNS servers you just configured:

# nslookup host1.test.example.com

The output from this command should be:

Output: Server: 10.20.30.13 Address: 10.20.30.13#53 Name: host1.test.example.com Address: 10.20.55.154

You can also test the reverse lookup by querying the DNS server with the IP address of the host:

# nslookup 10.20.55.154

The output should look like this:

Output: Server: 10.20.30.13 Address: 10.20.30.13#53 154.55.20.10.in-addr.arpa name = host1.test.example.com.

Check if all of the hosts resolve correctly using the commands above, if they do that means that you’ve configured everything properly.

Adding a New Host to Your DNS Servers

If you need to add a host to your DNS servers just follow the steps below:

On the ns1 nameserver do the following:

- Create an A record in the forward zone file for the host and increment the value of the Serial variable.

- Create a PTR record in the reverse zone file for the host and increment the value of the Serial variable.

- Add your host’s private IP address to the trusted ACL in named.conf.options.

- Reload BIND using the following command: sudo service bind9 reload

On the ns2 nameserver do the following:

- Add your host’s private IP address to the trusted ACL in named.conf.options.

- Reload BIND using the following command: sudo service bind9 reload

On the host machine do the following:

- Edit /etc/resolv.conf and change the nameservers to your DNS servers.

- Use nslookup to test if the host queries your DNS servers.

Removing a Existing Host from your DNS Servers

If you want to remove the host from your DNS servers just undo the steps above.

Note: Please subsitute the names and IP addresses used in this tutorial for the names and IP addresses of the hosts in your own private network.