GNU grep is an amazing power tool for finding words, numbers, spaces, punctuation, and random text strings inside of files, and this introduction will get you up and running quickly.

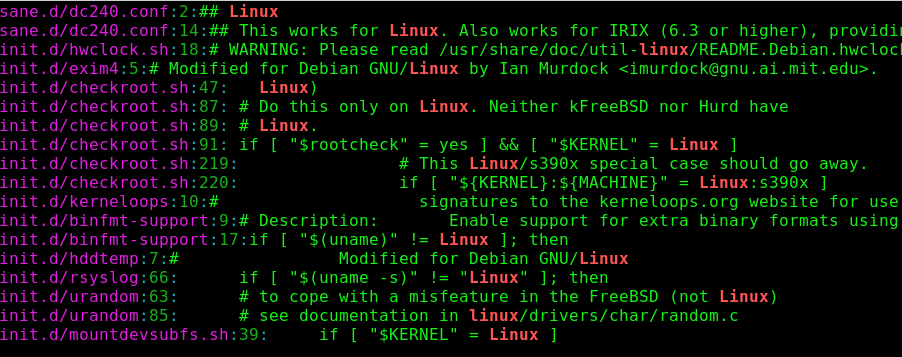

We’ll stick to GNU grep and the Bash shell, because both are the defaults on most Linux distros. You can verify that you have GNU grep, and not some other grep:

$grep -V

grep (GNU grep) 2.21

Copyright (C) 2014 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

It’s unlikely that you will bump into a non-GNU grep on Linux unless you put it there. There are some differences between GNU grep and Unix grep, and these are often discussed in documentation and forums as though we spend our days traipsing through multiples Linuxes and Unixes with gay abandon. Which sounds like fun, but if you use only Linux then you don’t need to worry about any differences.

Basic grep

We humans tend to think in terms of the numbers, words, names, and typos we want to find, but grep doesn’t know about these things; it looks for patterns of text strings to match. That is why you see the phrase “pattern matching” when you’re studying grep and other GNU text-processing tools.

I suggest making a plain text file to use for practicing the following examples because it limits the scope, and you can quickly make changes.

Most of us know how to use grep in simple ways, like finding all occurrences of a word in a file. First type your search term, and then the file to search:

$ grep word filename

By default, grep performs a case-sensitive search. You can perform a recursive case-insensitive search in a directory and its subdirectories:

$ grep -ir word dirname

This is an easy and useful way to find things, but it has a disadvantage: grep doesn’t look for words, it looks for text strings, so when you search for “word” grep thinks that “wordplay” and “sword” are matches. When you want an exact word match use -w:

$ grep -w word filename

Use ^ and $ to find matches at the beginnings and ends of lines:

$ grep ^word filename

$ grep word$ filename

Use -v to invert your match and find the lines that do not contain your search string:

$ grep -v word filename

You can search a list of space-delimited files, which is useful when you have just a few files to search. grep prefixes each match with its filename, so you know which files your matches are in:

$ grep word filename1 filename2 filename3

filename1:Most of us know how to use <code>grep</code> in simple ways

filename2:<pre><code>$ grep word filename</code></pre>

filename3:This is an easy and useful way to find things

You can also see the line numbers with -n, which is fab for large files:

$ grep -n word filename1 filename2 filename3

Sometimes you want to see the surrounding lines, for example when you’re searching log or configuration files. The -Cn option prints the number of preceding and following lines that you specify, which in this example is 4:

$ grep -nC4 word filename

Use -Bn to print your desired number of lines before your match, and -An after.

So how do you search for phrases when grep sees the word after a space as a filename? Search for phrases by enclosing them in single quotes:

$ grep 'two words' filename

What about double quotes? These behave differently than single quotes in Bash. Single quotes perform a literal search, so use these for plain text searches. Use double quotes when you want shell expansion on variables. Try it with this simple example: first create a new Bash variable using a text string that is in your test file, verify it, and then use grep to find it:

$ VAR1=strings

$ echo $VAR1

strings

$ grep "$VAR1" filename

strings

Wildcards

Now let’s play with wildcards. The . matches any single character except newlines. I could use this to match all occurrences of “Linuxes” and “Unixes” in this article:

$ grep -w Linux.. grep_cheat_sheet.html

$ grep -w Unix.. grep_cheat_sheet.html

Or do it in one command:

$ grep -wE '(Linux..|Unix..)' grep_cheat_sheet.html

That is an OR search that matches either one. What about an AND search to find lines that contain both? It looks a little clunky—but this is how it’s done, piping the results of the first grep search to the second one:

$ grep -w Linux.. grep_cheat_sheet.html |grep -w Unix..

I use this one for finding HTML tag pairs:

$ grep -i '<h3>.*</h3>' filename

Or find all header tags:

$ grep -i '<h.>.*</h.>' filename

You need both the dot and the asterisk to behave as a wildcard that matches anything: . means “match a single character,” and * means “match the preceding element 0 or more times.”

Bracket Expressions

Bracket expressions find all kinds of complicated matches. grep matches anything inside the brackets that it finds. For example, you can find specific upper- and lower-case matches in a word:

$ grep -w '[lL]inux' filename

This example finds all lines with pairs of parentheses that are enclosing any letters and spaces. A-Z and a-z define a range of patterns, A to Z inclusive uppercase, and a to z inclusive lowercase. For a space simply press the spacebar, and you can make it any number of spaces you want:

$ grep '([A-Za-z ]*)' filename

Character classes are nice shortcuts for complicated expressions. This example finds all of your punctuation, and uses the -o option to display only the punctuation and not the surrounding text:

$ grep -o "[[:punct:]]" filename

<

>

,

.

<

/

>

That example isn’t all that practical, but it looks kind of cool. A more common type of search is using character classes to find lines that start or end with numbers, letters, or spaces. This example finds lines that start with numbers:

$ grep "^[[:digit:]]" filename

Trailing spaces goof up some scripts, so find them with the space character class:

$ grep "[[:space:]]$" filename

Basic Building Blocks

These are the basic building blocks of grep searches. When you understand how these work, you’ll find that the advanced incantations are understandable. GNU grep is ancient and full of functionality, so study the GNU grep manual or man grep to dig deeper.

Learn more about system management in the Essentials of System Administration training course from The Linux Foundation.