Learn how to locate files in this tutorial from our archives.

It’s not uncommon for a sysadmin to have to find needles buried deep inside haystacks. On a busy machine, there can be hundreds of thousands of files present on your filesystems. What do you do when you need to make sure one particular configuration file is up to date, but you can’t remember where it is located?

If you’ve used Unix-type machines for a while, then you’ve almost certainly come across the find command before. It is unquestionably exceptionally sophisticated and highly functional. Here’s an example that just searches for links inside a directory, ignoring files:

# find . -lname "*"

You can do seemingly endless things with the find command; there’s no denying that. The find command is nice and succinct when it wants to be, but it can also get complex very quickly. This is not necessarily because of the find command itself, but coupled with “xargs” you can pass it all sorts of options to tune your output, and indeed delete those files which you have found.

Location, location, frustration

There often comes a time when simplicity is the preferred route, however — especially when a testy boss is leaning over your shoulder, chatting away about how time is of the essence. And, imagine trying to vaguely guess the path of the file you’ve never seen but that your boss is certain lives somewhere on the busy /var partition.

Step forward mlocate. You may be aware of one of its close relatives: slocate, which securely (note the prepended letter s for secure) took note of the pertinent file permissions to prevent unprivileged users from seeing privileged files). Additionally, there is also the older, original locate command whence they came.

The differences between mlocate and other members of its family (according to mlocate at least) is that, when scanning your filesystems, mlocate doesn’t need to continually rescan all your filesystem(s). Instead, it merges its findings (note the prepended m for merge) with any existing file lists, making it much more performant and less heavy on system caches.

In this series of articles, we’ll look more closely at the mlocate tool (and simply refer to it as “locate” due to its popularity) and examine how to quickly and easily tune it to your heart’s content.

Compact and Bijou

If you’re anything like me unless you reuse complex commands frequently then ultimately you forget them and need to look them up.The beauty of the locate command is that you can query entire filesystems very quickly and without worrying about top-level, root, paths with a simple command using locate.

In the past, you might well have discovered that the find command can be very stubborn and cause you lots of unwelcome head-scratching. You know, a missing semicolon here or a special character not being escaped properly there. Let’s leave the complicated find command alone now, relax, and have a look into the clever little command that is locate.

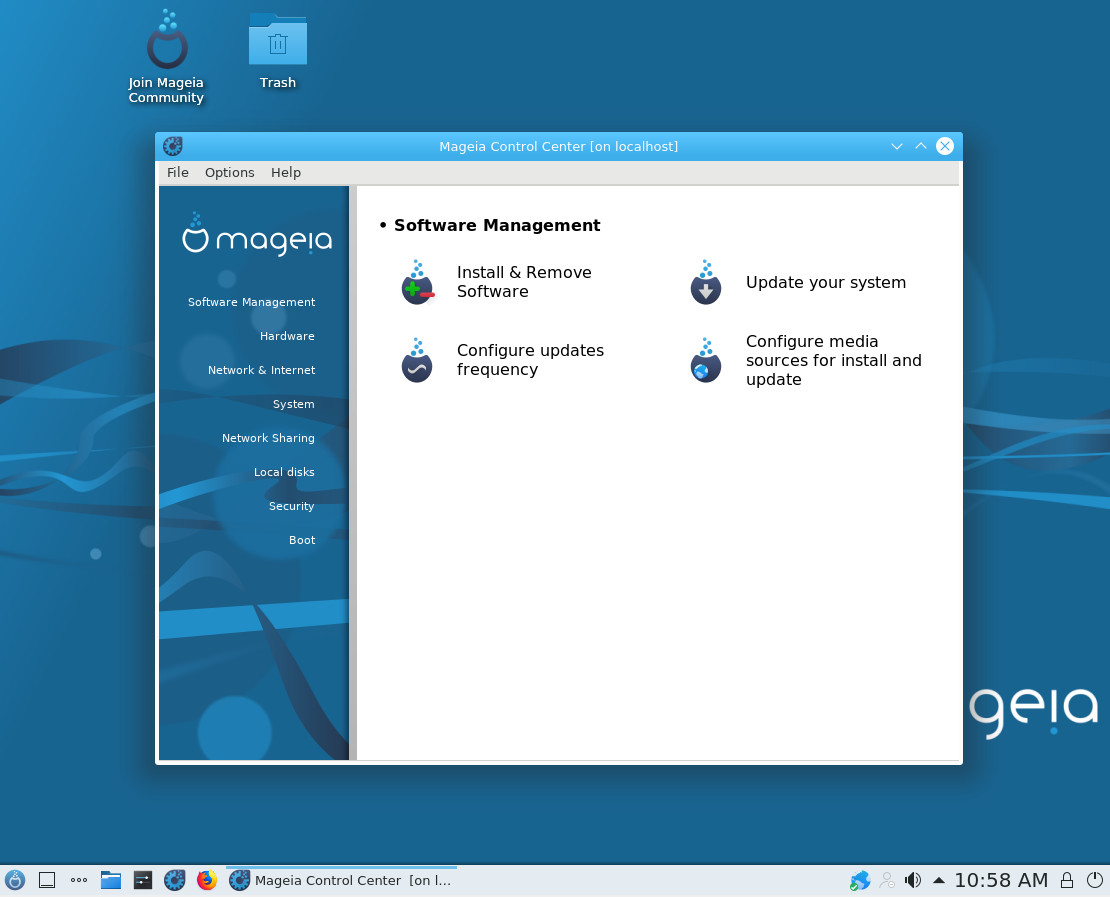

You will most likely want to check that it’s on your system first by running these commands:

For Red Hat derivatives:

# yum install mlocate

For Debian derivatives:

# apt-get install mlocate

There shouldn’t be any differences between distributions, but there are almost certainly subtle differences between versions; beware.

Next, we’ll introduce a key component to the locate command, namely updatedb. As you can probably guess, this is the command which updates the locate command’s db. Hardly counterintuitive.

The db is the locate command’s file list, which I mentioned earlier. That list is held in a relatively simple and highly efficient database for performance. The updatedb runs periodically, usually at quiet times of the day, scheduled via a cron job. In Listing 1, we can see the innards of the file /etc/cron.daily/mlocate.cron (both the file’s path and its contents might possibly be distro and version dependent).

#!/bin/sh nodevs=$(< /proc/filesystems awk '$1 == "nodev" { print $2 }') renice +19 -p $$ >/dev/null 2>&1 ionice -c2 -n7 -p $$ >/dev/null 2>&1 /usr/bin/updatedb -f "$nodevs"

Listing 1: How the “updatedb” command is triggered every day.

As you can see, the mlocate.cron script makes careful use of the excellent nice commands in order to have as little impact as possible on system performance. I haven’t explicitly stated that this command runs at a set time every day (although if my addled memory serves, the original locate command was associated with a slow-down-your-computer run scheduled at midnight). This is thanks to the fact that on some “cron” versions delays are now introduced into overnight start times.

This is probably because of the so-called Thundering Herd of Hippos problem. Imagine lots of computers (or hungry animals) waking up at the same time to demand food (or resources) from a single or limited source. This can happen when all your hippos set their wristwatches using NTP (okay, this allegory is getting stretched too far, but bear with me). Imagine that exactly every five minutes (just as a “cron job” might) they all demand access to food or something otherwise being served.

If you don’t believe me then have a quick look at the config from — a version of cron called anacron, in Listing 2, which is the guts of the file /etc/anacrontab.

# /etc/anacrontab: configuration file for anacron # See anacron(8) and anacrontab(5) for details. SHELL=/bin/sh PATH=/sbin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin MAILTO=root # the maximal random delay added to the base delay of the jobs RANDOM_DELAY=45 # the jobs will be started during the following hours only START_HOURS_RANGE=3-22 #period in days delay in minutes job-identifier command 1 5 cron.daily nice run-parts /etc/cron.daily 7 25 cron.weekly nice run-parts /etc/cron.weekly @monthly 45 cron.monthly nice run-parts /etc/cron.monthly

Listing 2: How delays are introduced into when “cron” jobs are run.

From Listing 2, you have hopefully spotted both “RANDOM_DELAY” and the “delay in minutes” column. If this aspect of cron is new to you, then you can find out more here:

# man anacrontab

Failing that, you can introduce a delay yourself if you’d like. An excellent web page (now more than a decade old) discusses this issue in a perfectly sensible way. This website discusses using sleep to introduce a level of randomality, as seen in Listing 3.

#!/bin/sh

# Grab a random value between 0-240.

value=$RANDOM

while [ $value -gt 240 ] ; do

value=$RANDOM

done

# Sleep for that time.

sleep $value

# Syncronize.

/usr/bin/rsync -aqzC --delete --delete-after masterhost::master /some/dir/

Listing 3: A shell script to introduce random delays before triggering an event, to avoid a Thundering Herd of Hippos.

The aim in mentioning these (potentially surprising) delays was to point you at the file /etc/crontab, or the root user’s own crontab file. If you want to change the time of when the locate command runs specifically because of disk access slowdowns, then it’s not too tricky. There may be a more graceful way of achieving this result, but you can also just move the file /etc/cron.daily/mlocate.cron somewhere else (I’ll use the /usr/local/etc directory), and as the root user add an entry into the root user’s crontab with this command and then paste the content as below:

# crontab -e 33 3 * * * /usr/local/etc/mlocate.cron

Rather than traipse through /var/log/cron and its older, rotated, versions, you can quickly tell the last time your cron.daily jobs were fired, in the case of anacron at least, with:

# ls -hal /var/spool/anacron

Next time, we’ll look at more ways to use locate, updatedb, and other tools for finding files.

Learn more about essential sysadmin skills: Download the Future Proof Your SysAdmin Career ebook now.

Chris Binnie’s latest book, Linux Server Security: Hack and Defend, shows how hackers launch sophisticated attacks to compromise servers, steal data, and crack complex passwords, so you can learn how to defend against these attacks. In the book, he also talks you through making your servers invisible, performing penetration testing, and mitigating unwelcome attacks. You can find out more about DevSecOps and Linux security via his website (http://www.devsecops.cc).