The topic of 5G mobile networks dominated the recent Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, despite the expectation that widespread usage may be years away. While 5G’s mind-boggling bandwidth captivates our attention, another interesting angle is found in the potential integration with software defined radio (SDR), as seen in OpenAirInterface’s proposed Cloud-RAN (C-RAN) software-defined radio access network.

As the leading purveyor of open source SDR solutions, UK-based Lime Microsystems is well positioned to play a key role in the development of 5G SDR. SDR enables the generation and augmentation of just about any wireless protocol without swapping hardware, thereby affordably enabling complex networks across a range of standards and frequencies.

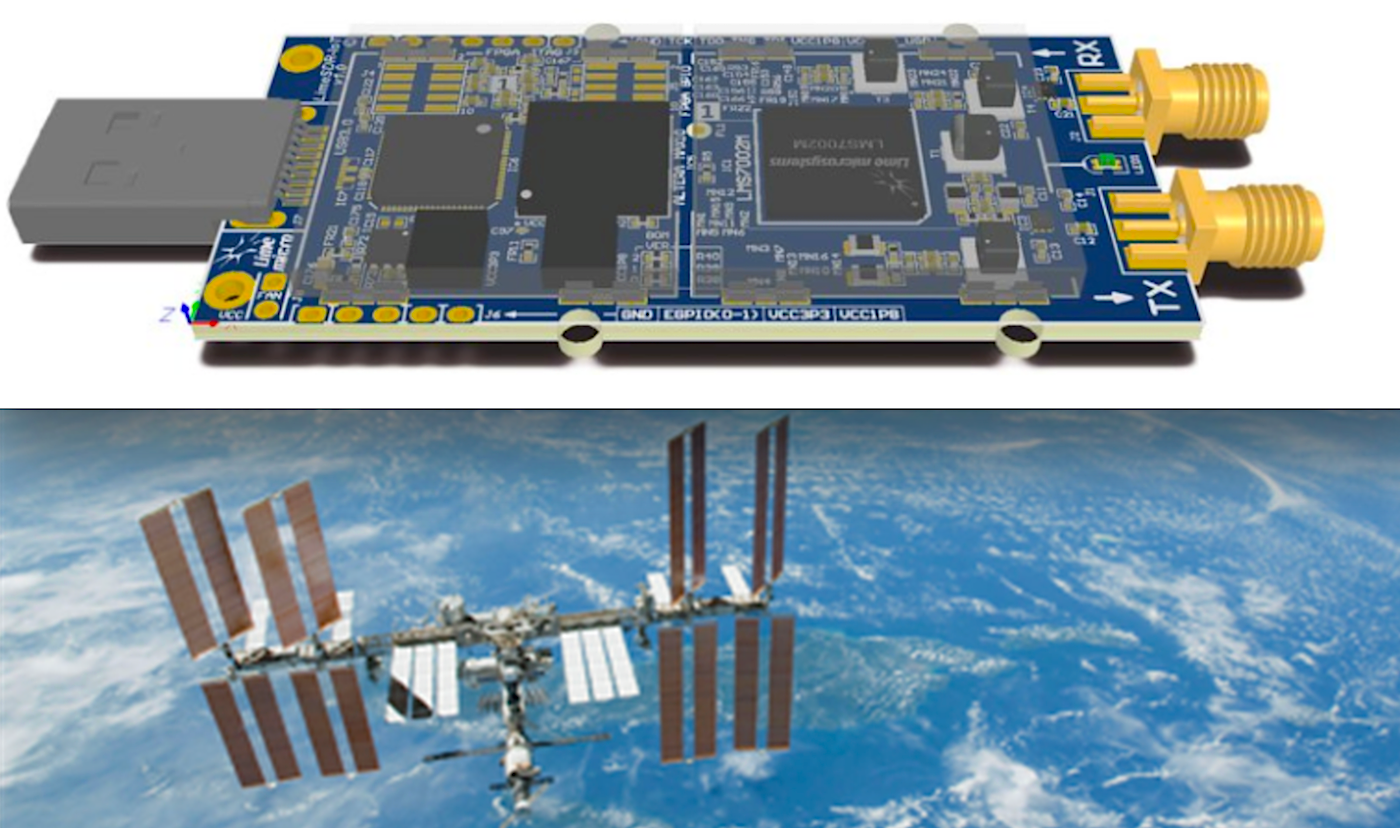

In late February, Lime announced a collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA) to make 200 of its Ubuntu Core-driven LimeSDR Mini boards available for developing applications running on ESA’s communications satellites, as part of ESA’s Advanced Research in Telecommunications Systems (ARTES) program. The Ubuntu Core-based, Snap-packaged satcom apps will include prototypes of SDR-enabled 5G satellite networks.

Other applications will include IoT networks controlled by fleets of small, low-cost CubeSat satellites. CubeSats, as well as smaller NanoSats, have been frequently used for open source experimentation. The applications will be shared in an upcoming SDR App Store for Satcom to be developed by Lime and Canonical.

LimeSDR Mini Starts Shipping

Lime Microsystems recently passed a major milestone when its ongoing Crowd Supply campaign for the LimeSDR Mini passed the $500,000 mark. On Mar. 4, the company reported it had shipped the first 300 boards to backers, with plans to soon ship 900 more.

At MWC, Lime demonstrated the LimeSDR Mini and related technologies working with Quortus’ cellular core and Amarisoft’s LTE stack. There was also a demonstration with Vodafone regarding the carrier’s plans to use Lime’s related LimeNET computers to help develop Vodafone’s Open RAN initiative.

Back in May 2016, Lime expanded beyond its business of building field programmable RF (FPRF) transceivers for wireless broadband systems when it successfully launched the $299, open spec LimeSDR board. The $139 LimeSDR Mini that was unveiled last September has a lower-end Intel/Altera FPGA — a MAX 10 instead of a Cyclone IV — but uses the same Lime LS7002 RF transceiver chip. At 69×31.4mm, it’s only a third the size of the LimeSDR.

The LimeSDR boards can send and receive using UMTS, LTE, GSM, WiFi, Bluetooth, Zigbee, LoRa, RFID, Digital Broadcasting, Sigfox, NB-IoT, LTE-M, Weightless, and any other wireless technology that can be programmed with SDR. The boards drive low-cost, multi-lingual cellular base stations and wireless IoT gateways, and are used for various academic, industrial, hobbyist, and scientific SDR applications, such as radio astronomy.

Raspberry Pi integration

Unlike the vast majority of open source Linux hacker boards, the LimeSDR boards don’t run Linux locally. Instead, their FPGAs manage DSP and interfacing tasks, while a USB 3.0-connected host system running Ubuntu Core provides the UI and high-level supervisory functions. Yet, the LimeSDR Mini can be driven by a Raspberry Pi or other low-cost hacker board that supports Ubuntu Core instead of requiring an x86-based desktop

In late January, the LimeSDR Mini campaign added a Raspberry Pi compatible Grove Starter Kit option with a GrovePi+ board, 15 Grove sensor and actuator modules, and dual antennas for 433/868/915MHz bands. Lime is supporting the kit with its LimeSDR optimized ScratchRadio extension.

Around the same time, Lime announced an open source prototype hack that combines a LimeSDR Mini board, a Raspberry Pi Zero, and a PiCam. Lime calls the DVB (digital video broadcasting) based prototype “one of the world’s smallest DVB transmitters.”

Compared to the LimeSDR, the LimeSDR Mini has a reduced frequency range, RF bandwidth, and sample rate. The board operates at 10MHz to 3.5 GHz compared to 100 kHz to 3.8 GHz for the original. Both models, however, can achieve up to 10 GHz frequencies with the help of an LMS8001 Companion board that was added as a LimeSDR Mini stretch goal project in October.

With Ubuntu Core’s Snap application packages and support for app marketplaces, LimeSDR apps can easily be downloaded, installed, developed, and shared. The drivers that run on the Ubuntu host system are developed with an open source Lime Suite library.

Lime was one of the earliest supporters of the lightweight, transactional Ubuntu Core, in part because it’s designed to ease OTA updates — a chief benefit of SDR. Ubuntu Core continues to steadily expand on hacker boards such as the Orange Pi, as well as on smart home hubs and IoT gateways like Rigado’s recently updated Vesta IoT gateways. The use of Ubuntu Core has helped to quickly expand the open LimeSDR development community.

LimeNET expands on the high end

In May 2017, Lime Microsystems launched three open source embedded LimeNET computers that don’t require a separate tethered computer. The LimeNET Mini, LimeNET Enterprise, and LimeNET Base Station, which range in price from $2,600 to over $17,000, run Ubuntu Core on various 14nm fabricated Intel Core processors. They offer a variety of ports, antennas, WiFi, Bluetooth, and other features that turn the underlying LimeSDR boards into wireless base stations.

The top-of-the-line LimeNET Base Station features dual RF transceiver chips, as well as a LimeNET QPCIe variant of the LimeSDR board with a faster PCIe interface instead of USB. It also adds an amplifier with dual MIMO units that greatly expands the range beyond the 15-meter limit of the other LimeNET systems. If you don’t want this separately available LimeNET Amplifier Chassis, you can buy LimeNET QPCIe board as part of a cheaper LimeNET Core system.

Lime’s boards and systems aren’t the only low-cost SDR solutions running on Linux. Last year, for example, Avnet launched a Linux- and Xilinx Zynq-7020 based PicoZed SDR computer-on-module. Earlier products include the Epiq Solutions Matchstiq Z1, a handheld system that runs Linux on an iVeia Atlas-I-Z7e module equipped with a Zynq Z-7020.

Sign up for ELC/OpenIoT Summit updates to get the latest information: