Kubernetes is open source software for automating deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications. The project is governed by the Cloud Native Computing Foundation, which is hosted by The Linux Foundation. And it’s quickly becoming the Linux of the cloud, says Jim Zemlin, executive director of The Linux Foundation.

Running a container on a laptop is relatively simple. But connecting containers across multiple hosts, scaling them when needed, deploying applications without downtime, and service discovery among several aspects, are really hard challenges. Kubernetes addresses those challenges with a set of primitives and a powerful API.

A key aspect of Kubernetes is that it builds on 15 years of experience at Google, which donated the technology to CNCF in 2015. Google infrastructure started reaching high scale before virtual machines became pervasive in the datacenter, and containers provided a fine-grained solution to pack clusters efficiently.

In this blog series, we introduce you to LFS258: Kubernetes Fundamentals, the Linux Foundation Kubernetes training course. The course is designed for Kubernetes beginners, and will teach students to deploy a containerized application, and how to manipulate resources via the API. You can download the sample chapter now.

The Meaning of Kubernetes

“Kubernetes” means the helmsman, or pilot of the ship. In keeping with the maritime theme of Docker containers, Kubernetes is the pilot of a ship of containers.

Challenges

Containers have seen a huge rejuvenation in the past three years. They provide a great way to package, ship, and run applications. The developer experience has been boosted tremendously thanks to containers. Containers, and Docker specifically, have empowered developers with ease of building container images, and simplicity of sharing images via Docker registries.

However, managing containers at scale and architecting a distributed application based on microservices’ principles is still challenging. You first need a continuous integration pipeline to build your container images, test them, and verify them. Then you need a cluster of machines acting as your base infrastructure on which to run your containers. You also need a system to launch your containers, watch over them when things fail, and self-heal. You must be able to perform rolling updates and rollbacks, and you need a network setup which permits self-discovery of services in a very ephemeral environment.

Kubernetes Architecture

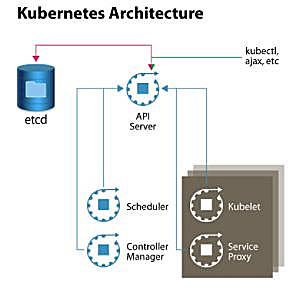

To quickly de-mystify Kubernetes, let’s have a look at Figure 1, which shows a high-level architecture diagram of the system components. In its simplest form, Kubernetes is made of a central manager (aka master) and some worker nodes. (You will learn in the course how to run everything on a single node for testing purposes).

The manager runs an API server, a scheduler, a controller, and a storage system to keep the state of the cluster. Kubernetes exposes an API via the API server so you can communicate with the API using a local client called kubectl, or you can write your own client. The scheduler sees the requests for running containers coming to the API and finds a suitable node to run that container in.

Each node in the cluster runs two processes: a kubelet and a service proxy. The kubelet receives requests to run the containers and watches over them on the local node. The proxy creates and manages networking rules to expose the container on the network.

In a nutshell, Kubernetes has the following characteristics:

-

It is made of a manager and a set of nodes

-

It has a scheduler to place containers in a cluster

-

It has an API server and a persistence layer with etcd

-

It has a controller to reconcile states

-

It is deployed on VMs or bare-metal machines, in public clouds, or on-premise

-

It is written in Go

How Is Kubernetes Doing?

Since its inception, Kubernetes has seen a terrific pace of innovation and adoption. The community of developers, users, testers, and advocates is continuously growing every day. The software is also moving at an extremely fast pace, which is even putting GitHub to the test. Here are a few numbers:

-

It was open sourced in June 2014

-

It has 1,000+ contributors

-

There are 37k+ commits

-

There have been meetups in over 100 cities worldwide, with over 30,000 participants in 25 countries

-

There are over 8,000 people on Slack

-

There is one major release approximately every three months

To see more interesting numbers about the Kubernetes community, you can check the infographic created by Apprenda.

Who Uses Kubernetes?

Kubernetes is being adopted at a rapid pace. To learn more, you should check out the case studies presented on Kubernetes.io. eBay, box, Pearson, and Wikimedia have all shared their stories. Pokemon Go, the fastest growing mobile game, runs on Google Container Engine (GKE), the Kubernetes service from Google Cloud Platform (GCP).

In this article, we talked about what Kubernetes is, what it does, and took a look at its architecture. Next week in this series, we’ll compare Kubernetes to competing container managers.

Download the sample chapter now.

Meet Your Instructor: Sebastien Goasguen

This blog series is adapted from materials prepared by course instructor Sebastien Goasguen, a 15-year open source veteran. He wrote the O’Reilly Docker Cookbook and, while investigating the Docker ecosystem, he started focusing on Kubernetes. He is the founder of Skippbox, a Kubernetes startup that provides solutions, services, and training for this key cloud-native technology, and Senior Director of Cloud Technologies for Bitnami. He is also a member of the Apache Software Foundation and a member/contributor to the Kubernetes Incubator.