What is Docker?

Docker is an open source tool that automates the deployment of the application inside software container.

The easiest way to get the idea behind Docker is to compare it to, well… standard shipping containers.

Back in the days, transportation companies faced the following challenges:

- How to transport different (incompatible) types of goods side by side (like food and chemicals or glass and bricks).

- How to handle packages of the various sizes by the same vehicle.

With the introduction of containers, bricks can be put over glass, and chemicals can be stored next to food. Cargo of the various size can be put inside a standardized container that can be loaded/unloaded by the same vehicle.

Note: the code samples may be displayed improperly because of markdown. I recommend to continue reading the original article on our blog to make sure all the examples are displayed properly.

Let’s go back to containers in software development.

When you develop an application, you need to provide your code alongside with all possible dependencies like libraries, web server, databases, etc. You may end up in a situation when the application is working on your computer but won’t even start on stage server, dev or a QA’s machine.

This challenge can be addressed by isolating the app to make it independent of the system.

What is the difference from virtualization?

Traditionally virtual machines were used to avoid this unexpected behavior. The main problem with VM is that “extra OS” on top of the host operating system adds gigabytes of space to the project. Most of the time your server will host several VMs that will take even more space. And by the way, at the moment most cloud-based server providers will charge you for that extra space. Another significant drawback of VM is a slow boot.

Docker eliminates all the above by simply sharing OS kernel across all the containers that are running as separate processes of the host OS.

Keep in mind that Docker is not the first and not the only containerization platform. However, at the moment Docker is the biggest and the most powerful player on the market.

Why do we need Docker?

The list of benefits is the following:

- Faster development process. There is no need to install 3rd parties like PostgreSQL, Redis, Elasticsearch. Those can be run in containers.

- Handy application encapsulation (you can deliver your application in one piece).

- Same behaviour on local machine / dev / stage / production servers.

- Easy and clear monitoring.

- Easy to scale (if you’ve done your application right it will be ready to scaling not only in Docker).

Supported platforms

Docker’s native platform is Linux, as it’s based on features provided by Linux kernel. However, you can still run it on macOS and Windows. The only difference is that on macOS and Windows Docker is encapsulated into a tiny virtual machine. At the moment Docker for macOS and Windows has reached a significant level of usability and feels more like a native app.

Moreover, there a lot of supplementary apps such as

Kitematic or Docker Machine which help to install and operate Docker on non Linux platforms.

Installation

You can check the installation instructions here.

If you’re running Docker on Linux you need to run all the following commands as root or you can add your user to docker group and re-login:

sudo usermod -aG docker $(whoami)

Terminology

-

Container — running instance that encapsulates required software. Containers are always created from images.

Container can expose ports and volumes to interact with other containers or/and outer world.

Container can be easily killed / removed and re-created again in a very short time. -

Image — basic element for every container. When you create an image every step is cached and can be reused (Copy On Write model). Depending on the image it can take some time to build it. Containers, on the other hand can be started from images right away.

-

Port — a TCP/UDP port in its original meaning. To keep things simple let’s assume that ports can be exposed to the outer world (accessible from host OS) or connected to other containers — accessible only from those containers and invisible to the outer world.

-

Volume — can be described as a shared folder. Volumes are initialized when a container is created. Volumes are designed to persist data, independent of the container’s lifecycle.

-

Registry — the server that stores Docker images. It can be compared to Github — you can pull an image from the registry to deploy it locally, and you can push locally built images to the registry.

-

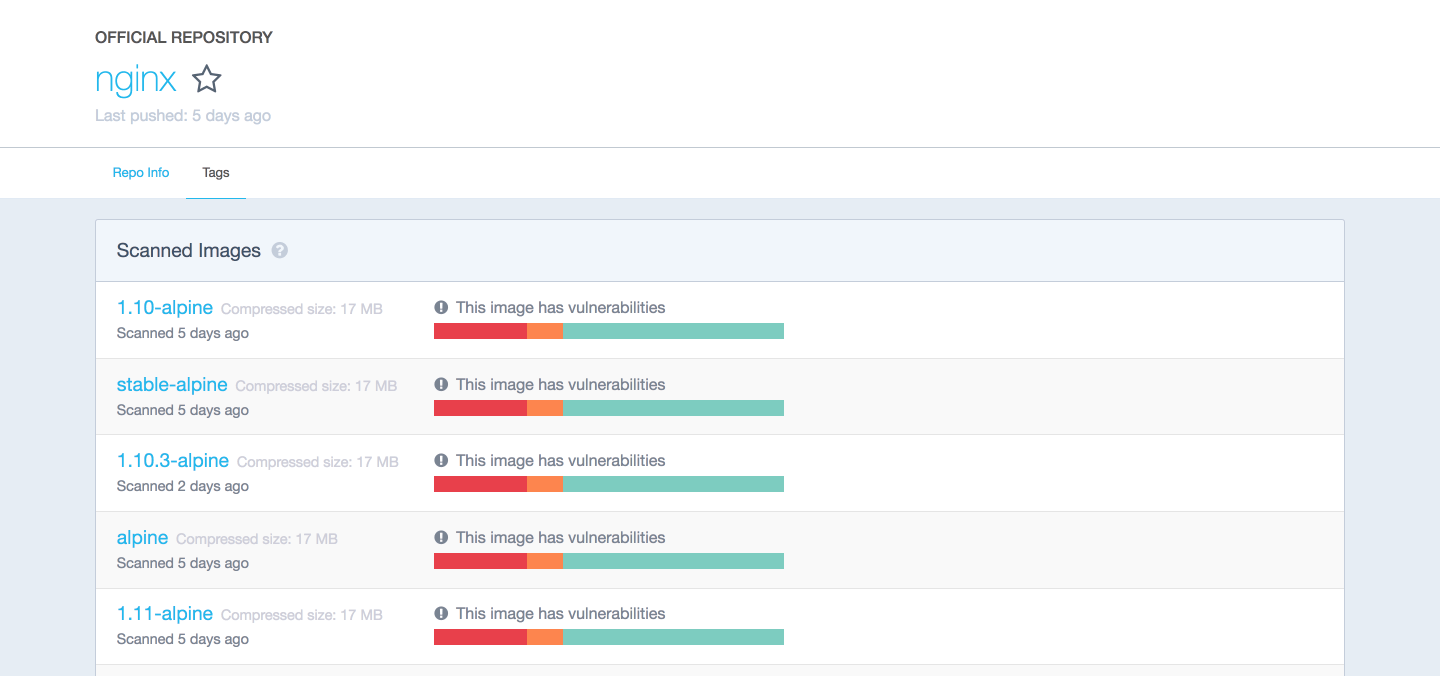

Docker hub — a registry with web-interface provided by Docker Inc. It stores a lot of Docker images with different software. Docker hub is a source of the “official” Docker images made by Docker team or made in cooperation with the original software manufacturer (it doesn’t necessary mean that these “original” images are from official software manufacturers). Official images list their potential vulnerabilities. This information is available for any logged in user. There are both free and paid accounts available. You can have one private image per account and an infinite amount of public images for free.

Example 1: hello world

It’s time to run your first container:

docker run ubuntu /bin/echo 'Hello world'

Console output:

Unable to find image 'ubuntu:latest' locally

latest: Pulling from library/ubuntu

d54efb8db41d: Pull complete

f8b845f45a87: Pull complete

e8db7bf7c39f: Pull complete

9654c40e9079: Pull complete

6d9ef359eaaa: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:dd7808d8792c9841d0b460122f1acf0a2dd1f56404f8d1e56298048885e45535

Status: Downloaded newer image for ubuntu:latest

Hello world

- docker run is a command to run a container.

- ubuntu is the image you run, for example, the Ubuntu operating system image. When you specify an image, Docker looks first for the image on your Docker host. If the image does not exist locally, then the image is pulled from the public image registry — Docker Hub.

- /bin/echo ‘Hello world’ is the command that will run inside a new container. This container simply prints Hello world and stops the execution.

Let’s try to create an interactive shell inside Docker container:

docker run -i -t --rm ubuntu /bin/bash

- -t flag assigns a pseudo-tty or terminal inside the new container.

- -i flag allows you to make an interactive connection by grabbing the standard input (STDIN) of the container.

- –rm flag to automatically remove the container when the process exits. By default, containers are not deleted. This container exists until we keep the shell session and terminates when we exit from the session (like SSH session to a remote server).

If you want to keep container running after the end of the session, you need to daemonize it:

docker run --name daemon -d ubuntu /bin/sh -c "while true; do echo hello world; sleep 1; done"

- –name daemon assigns daemon name to a new container. If you don’t specify a name explicitly, Docker will generate and assign it automatically.

- -d flag runs the container in the background (daemonize it).

Let’s see what containers we have at the moment:

docker ps -a

Console output:

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

1fc8cee64ec2 ubuntu "/bin/sh -c 'while..." 32 seconds ago Up 30 seconds daemon

c006f1a02edf ubuntu "/bin/echo 'Hello ..." About a minute ago Exited (0) About a minute ago gifted_nobel

- docker ps is a command to list containers.

- -a shows all containers (without -a flag ps will show only running containers).

The ps shows us that we have two containers:

- gifted_nobel (name for this container was generated automatically – it will be different on your machine) – it’s the first container we’ve created which printed ‘Hello world’ once.

- daemon — it’s the third container we’ve created which runs as a daemon.

Note: there is no second container (the one with interactive shell) because we set –rm option. As a result, this container is automatically deleted right after execution.

Let’s check the logs and see what daemon container is doing right now:

docker logs -f daemon

Console output:

...

hello world

hello world

hello world

- docker logs fetches the logs of a container.

- -f flag to follow the log output (works actually like tail -f).

Now let’s stop daemon container:

docker stop daemon

Let’s make sure that the container has stopped.

docker ps -a

Console output:

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

1fc8cee64ec2 ubuntu "/bin/sh -c 'while..." 5 minutes ago Exited (137) 5 seconds ago daemon

c006f1a02edf ubuntu "/bin/echo 'Hello ..." 6 minutes ago Exited (0) 6 minutes ago gifted_nobel

The container is stopped. We can start it again:

docker start daemon

Let’s ensure that it is running:

docker ps -a

Console output:

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

1fc8cee64ec2 ubuntu "/bin/sh -c 'while..." 5 minutes ago Up 3 seconds daemon

c006f1a02edf ubuntu "/bin/echo 'Hello ..." 6 minutes ago Exited (0) 7 minutes ago gifted_nobel

Now let’s stop it again and remove all the containers manually:

docker stop daemon

docker rm <your first container name>

docker rm daemon

To remove all containers we can use the following command:

docker rm -f $(docker ps -aq)

- docker rm is command to remove container.

- -f flag (for rm) is to stop container if it’s running (force deletion).

- -q flag (for ps) is to print only container IDs.

Example 2: Nginx

Starting from this example you’ll need several additional files you can find on my GitHub repo.

You can clone my repo or simply use the following link to download the sample files.

It is time to create and run more meaningful container like Nginx.

Change the directory to examples/nginx.

docker run -d --name test-nginx -p 80:80 -v $(pwd):/usr/share/nginx/html:ro nginx:latest

Console output:

Unable to find image 'nginx:latest' locally

latest: Pulling from library/nginx

693502eb7dfb: Pull complete

6decb850d2bc: Pull complete

c3e19f087ed6: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:52a189e49c0c797cfc5cbfe578c68c225d160fb13a42954144b29af3fe4fe335

Status: Downloaded newer image for nginx:latest

436a602273b0ca687c61cc843ab28163c720a1810b09005a36ea06f005b0c971

- -p is a ports mapping HOST PORT:CONTAINER PORT.

- -v is a volume mounting HOST DIRECTORY:CONTAINER DIRECTORY.

Important: run command accepts only absolute paths. In our example we’ve used $(pwd) to set current directory absolute path.

Now you can check this url in your web browser.

We can try to change /example/nginx/index.html (which is mounted as a volume to/usr/share/nginx/html directory inside the container) and refresh the page.

Let’s get the information about test-nginx container:

docker inspect test-nginx

This command displays system wide information about the Docker installation. This information includes the kernel version, number of containers and images, exposed ports, mounted volumes, etc.

Example 3: writing Dockerfile

To build a Docker image you need to create a Dockerfile. It is a plain text file with instructions and arguments. Here is the description of the instructions we’re going to use in our next example:

- FROM — set base image

- RUN — execute command in container

- ENV — set environment variable

- WORKDIR — set working directory

- VOLUME — create mount-point for a volume

- CMD — set executable for container

You can check Dockerfile reference for more details.

Let’s create an image that will get the contents of the website with curl and store it to the text file. We need to pass website url via environment variable SITE_URL. Resulting file will be placed in a directory mounted as a volume.

FROM ubuntu:latest

RUN apt-get update

RUN apt-get install --no-install-recommends --no-install-suggests -y curl

ENV SITE_URL https://google.com/

WORKDIR /data

VOLUME /data

CMD sh -c "curl -L $SITE_URL > /data/results"

Dockerfile is ready, it’s time to build the actual image.

Go to examples/curl and execute the following command to build an image:

docker build . -t test-curl

Console output:

Sending build context to Docker daemon 3.584 kB

Step 1/7 : FROM ubuntu:latest

---> 0ef2e08ed3fa

Step 2/7 : RUN apt-get update

---> Running in 4aa839bb46ec

Get:1 http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu xenial InRelease [247 kB]

Get:2 http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu xenial-updates InRelease [102 kB]

...

Fetched 24.9 MB in 4s (5208 kB/s)

Reading package lists...

---> 35ac5017c794

Removing intermediate container 4aa839bb46ec

Step 3/7 : RUN apt-get install --no-install-recommends --no-install-suggests -y curl

---> Running in 3ca9384ecf8d

Reading package lists...

Building dependency tree...

Reading state information...

The following additional packages will be installed...

---> f3c6d26b95e6

Removing intermediate container 3ca9384ecf8d

Step 4/7 : ENV SITE_URL https://google.com/

---> Running in 21b0022b260f

---> 9a733ee39a46

Removing intermediate container 21b0022b260f

Step 5/7 : WORKDIR /data

---> c024301ddfb8

Removing intermediate container 3bc973e5584c

Step 6/7 : VOLUME /data

---> Running in a9594a8958fe

---> 6802707a7114

Removing intermediate container a9594a8958fe

Step 7/7 : CMD sh -c "curl -L $SITE_URL > /data/results"

---> Running in 37503bc4e386

---> 5ebb2a65d771

Removing intermediate container 37503bc4e386

Successfully built 5ebb2a65d771

- docker build builds a new image locally.

- -t flag sets the name tag to an image.

Now we have the new image and we can see it in the list of existing images:

docker images

Console output:

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

test-curl latest 5ebb2a65d771 37 minutes ago 180 MB

nginx latest 6b914bbcb89e 7 days ago 182 MB

ubuntu latest 0ef2e08ed3fa 8 days ago 130 MB

We can create and run container from the image. Let’s try it with default parameters:

docker run --rm -v $(pwd)/vol:/data/:rw test-curl

To see results saved to file run:

cat ./vol/results

Let’s try with facebook.com:

docker run --rm -e SITE_URL=https://facebook.com/ -v $(pwd)/vol:/data/:rw test-curl

To see results saved to file run:

cat ./vol/results

Best practices of creating images

- Include only necessary context — use a .dockerignore file (like .gitignore in git)

- Avoid installing unnecessary packages — it will consume extra disk space

- Use cache. Add context which changes a lot (for example source code of your project) at the end of Dockerfile — it will utilize Docker cache effectively.

- Be careful with volumes. You should remember what data is in volumes. Because volumes are persistent and don’t die with the containers – next container will use data from volume which was created by previous container.

- Use environment variables (in RUN, EXPOSE, VOLUME). It will make your Dockerfile more flexible.

Connection between containers

Docker compose — is the only right way to connect containers with each other.

Example 4: docker-compose Python + Redis

In this example, I am going to connect Python and Redis containers.

version: '2'

services:

app:

build:

context: ./app

depends_on:

- redis

environment:

- REDIS_HOST=redis

ports:

- "5000:5000"

redis:

image: redis:3.2-alpine

volumes:

- redis_data:/data

volumes:

redis_data:

Go to examples/compose and execute the following command:

docker-compose --project-name app-test -f docker-compose.yml up

Console output:

Creating network "apptest_default" with the default driver

Creating volume "apptest_redis_data" with default driver

Pulling redis (redis:3.2-alpine)...

3.2-alpine: Pulling from library/redis

627beaf3eaaf: Pull complete

a503a4771a4a: Pull complete

72c5d910c683: Pull complete

6aadd3a49c30: Pull complete

adf925aa1ad1: Pull complete

0565da0f872e: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:9cd405cd1ec1410eaab064a1383d0d8854d1eef74a54e1e4a92fb4ec7bdc3ee7

Status: Downloaded newer image for redis:3.2-alpine

Building app

Step 1/9 : FROM python:3.5.2-alpine

3.5.2-alpine: Pulling from library/python

b7f33cc0b48e: Pull complete

8eda8bb6fee4: Pull complete

4613e2ad30ef: Pull complete

f344c00ca799: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:8efcb12747ff958de32b32424813708f949c472ae48ca28691078475b3373e7c

Status: Downloaded newer image for python:3.5.2-alpine

---> e70a322afafb

Step 2/9 : ENV BIND_PORT 5000

---> Running in 8518936700b3

---> 0f652cdd2cee

Removing intermediate container 8518936700b3

Step 3/9 : ENV REDIS_HOST localhost

---> Running in 027286e90699

---> 6da3674f79fa

Removing intermediate container 027286e90699

Step 4/9 : ENV REDIS_PORT 6379

---> Running in 0ef17cb512ed

---> c4c514aa3008

Removing intermediate container 0ef17cb512ed

Step 5/9 : COPY ./requirements.txt /requirements.txt

---> fd523d64faae

Removing intermediate container 8c94c82e0aa8

Step 6/9 : COPY ./app.py /app.py

---> be61f59b3cd5

Removing intermediate container 93e38cd0b487

Step 7/9 : RUN pip install -r /requirements.txt

---> Running in 49aabce07bbd

Collecting flask==0.12 (from -r /requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading Flask-0.12-py2.py3-none-any.whl (82kB)

Collecting redis==2.10.5 (from -r /requirements.txt (line 2))

Downloading redis-2.10.5-py2.py3-none-any.whl (60kB)

Collecting itsdangerous>=0.21 (from flask==0.12->-r /requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading itsdangerous-0.24.tar.gz (46kB)

Collecting Werkzeug>=0.7 (from flask==0.12->-r /requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading Werkzeug-0.11.15-py2.py3-none-any.whl (307kB)

Collecting Jinja2>=2.4 (from flask==0.12->-r /requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading Jinja2-2.9.5-py2.py3-none-any.whl (340kB)

Collecting click>=2.0 (from flask==0.12->-r /requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading click-6.7-py2.py3-none-any.whl (71kB)

Collecting MarkupSafe>=0.23 (from Jinja2>=2.4->flask==0.12->-r /requirements.txt (line 1))

Downloading MarkupSafe-1.0.tar.gz

Installing collected packages: itsdangerous, Werkzeug, MarkupSafe, Jinja2, click, flask, redis

Running setup.py install for itsdangerous: started

Running setup.py install for itsdangerous: finished with status 'done'

Running setup.py install for MarkupSafe: started

Running setup.py install for MarkupSafe: finished with status 'done'

Successfully installed Jinja2-2.9.5 MarkupSafe-1.0 Werkzeug-0.11.15 click-6.7 flask-0.12 itsdangerous-0.24 redis-2.10.5

---> 18c5d1bc8804

Removing intermediate container 49aabce07bbd

Step 8/9 : EXPOSE $BIND_PORT

---> Running in f277fa7dfcd5

---> 9f9bec2abf2e

Removing intermediate container f277fa7dfcd5

Step 9/9 : CMD python /app.py

---> Running in a2babc256093

---> 2dcc3b299859

Removing intermediate container a2babc256093

Successfully built 2dcc3b299859

WARNING: Image for service app was built because it did not already exist. To rebuild this image you must use `docker-compose build` or `docker-compose up --build`.

Creating apptest_redis_1

Creating apptest_app_1

Attaching to apptest_redis_1, apptest_app_1

redis_1 | 1:C 08 Mar 09:56:55.765 # Warning: no config file specified, using the default config. In order to specify a config file use redis-server /path/to/redis.conf

redis_1 | _._

redis_1 | _.-``__ ''-._

redis_1 | _.-`` `. `_. ''-._ Redis 3.2.8 (00000000/0) 64 bit

redis_1 | .-`` .-```. ```/ _.,_ ''-._

redis_1 | ( ' , .-` | `, ) Running in standalone mode

redis_1 | |`-._`-...-` __...-.``-._|'` _.-'| Port: 6379

redis_1 | | `-._ `._ / _.-' | PID: 1

redis_1 | `-._ `-._ `-./ _.-' _.-'

redis_1 | |`-._`-._ `-.__.-' _.-'_.-'|

redis_1 | | `-._`-._ _.-'_.-' | http://redis.io

redis_1 | `-._ `-._`-.__.-'_.-' _.-'

redis_1 | |`-._`-._ `-.__.-' _.-'_.-'|

redis_1 | | `-._`-._ _.-'_.-' |

redis_1 | `-._ `-._`-.__.-'_.-' _.-'

redis_1 | `-._ `-.__.-' _.-'

redis_1 | `-._ _.-'

redis_1 | `-.__.-'

redis_1 |

redis_1 | 1:M 08 Mar 09:56:55.767 # WARNING: The TCP backlog setting of 511 cannot be enforced because /proc/sys/net/core/somaxconn is set to the lower value of 128.

redis_1 | 1:M 08 Mar 09:56:55.767 # Server started, Redis version 3.2.8

redis_1 | 1:M 08 Mar 09:56:55.767 # WARNING overcommit_memory is set to 0! Background save may fail under low memory condition. To fix this issue add 'vm.overcommit_memory = 1' to /etc/sysctl.conf and then reboot or run the command 'sysctl vm.overcommit_memory=1' for this to take effect.

redis_1 | 1:M 08 Mar 09:56:55.767 # WARNING you have Transparent Huge Pages (THP) support enabled in your kernel. This will create latency and memory usage issues with Redis. To fix this issue run the command 'echo never > /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/enabled' as root, and add it to your /etc/rc.local in order to retain the setting after a reboot. Redis must be restarted after THP is disabled.

redis_1 | 1:M 08 Mar 09:56:55.767 * The server is now ready to accept connections on port 6379

app_1 | * Running on http://0.0.0.0:5000/ (Press CTRL+C to quit)

app_1 | * Restarting with stat

app_1 | * Debugger is active!

app_1 | * Debugger pin code: 299-635-701

Current example will increment view counter in Redis. Open the following url in your web browser and check it.

Using docker-compose is a topic for a separate article. To get started you can play with some images from Docker Hub or if you want to create your own images – follow best practices listed above. The only thing I can add in terms of using docker-compose: always give explicit names to your volumes in docker-compose.yml (if image has volumes). This simple rule will save you from issue in the future when you’ll be inspecting your volumes.

version: '2'

services:

...

redis:

image: redis:3.2-alpine

volumes:

- redis_data:/data

volumes:

redis_data:

In this case redis_data will be the name inside docker-compose.yml file, for the real volume name it will be prepended with project name prefix.

To see volumes run:

docker volume ls

Console output:

DRIVER VOLUME NAME

local apptest_redis_data

Without explicit volume name there will be UUID. And here is an example from my local machine:

DRIVER VOLUME NAME

local ec1a5ac0a2106963c2129151b27cb032ea5bb7c4bd6fe94d9dd22d3e72b2a41b

local f3a664ce353ba24dd43d8f104871594de6024ed847054422bbdd362c5033fc4c

local f81a397776458e62022610f38a1bfe50dd388628e2badc3d3a2553bb08a5467f

local f84228acbf9c5c06da7be2197db37f2e3da34b7e8277942b10900f77f78c9e64

local f9958475a011982b4dc8d8d8209899474ea4ec2c27f68d1a430c94bcc1eb0227

local ff14e0e20d70aa57e62db0b813db08577703ff1405b2a90ec88f48eb4cdc7c19

local polls_pg_data

local polls_public_files

local polls_redis_data

local projectdev_pg_data

local projectdev_redis_data

Docker way

Docker has some restrictions and requirements depending on the architecture of your system (applications that you pack into containers). You can ignore these requirements or find some workarounds, but in this case, you won’t get all the benefits from using Docker. My strong advice is to follow these recommendations:

- 1 application = 1 container

- Run process in foreground (don’t use systemd, upstart or any other similar tools)

- Keep data out of container — use volumes

- Do not use SSH (if you need to step into container you can use docker exec command)

- Avoid manual configurations (or actions) inside container

Conclusion

To summarize all the above, alongside with IDE and Git, Docker has become one of the must-have developer tools.

We at Django Stars have successfully implemented Docker in numerous projects. Stay tuned if you are interested in such advanced tutorials — “How to set up Django app in Docker?” and “How to use Docker and CircleCI?”.

This tutorial was originally posted in Django Stars Blog. Join the discussion if you have any questions

Have you already used Docker on your project? Leave us a comment or ask questions below!