This tutorial shows the installation and configuration of Monitorix on Ubuntu 16.04 (Xenial Xerus). Monitorix is a free, lightweight, open source monitoring tool designed to monitor as many services and system resources as possible on servers and desktops. It consists mainly of two programs: a collector, called Monitorix, which is a Perl daemon that is started automatically as a system service, and a CGI script called monitorix.cgi. Since 3.0 version Monitorix includes its own HTTP server built in, so you aren’t forced to install a third-party web server to use it.

No Objections to Object Stores: Everyone’s Going Smaller and Faster

A couple of weeks ago I published an article about high performance object storage. Reactions have been quite diverse. Some think that object stores can only be huge and slow and then others who think quite the opposite. In fact, they can also be fast and small.

In the last year I’ve had a lot of interesting conversations with end users and vendors concerning this topic. Having just covered the part about “fast object stores”, again I’d like to point out that by fast I mean “faster and with better latency than traditional object stores, but not as fast as block storage.”

This time round I’d like to talk about smaller object stores. Some startups are working on smaller object storage systems intentionally. They want to build small object storage systems by design – or better still, small footprint object storage systems)…

Read more at The Register

HPE Won’t Ignore Open Source NFV MANO

Now that we’ve got open source factions rivaling for attention in NFV management and network orchestration (MANO), it’s easy to forget that Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) has had a complete MANO stack for a while.

But that doesn’t mean the vendor won’t take an interest in Open Source MANO (OSM) and Open-O, two MANO efforts that are getting underway. OSM launched in February, while Open-O is preparing to kick off in June. The key is the projects’ open source nature. Carriers are determined to implement NFV using as many open source elements as possible, said Prodip Sen, HPE’s CTO of NFV, speaking with SDxCentral at the recent OpenStack Summit.

Read more at SDxCentral

Claude Shannon, the Father of the Information Age, Turns 1100100

Claude Shannon: Born on the planet Earth (Sol III) in the year 1916 A.D. Generally regarded as the father of the information age, he formulated the notion of channel capacity in 1948 A.D. Within several decades, mathematicians and engineers had devised practical ways to communicate reliably at data rates within one per cent of the Shannon limit.

As is sometimes the case with encyclopedias, the crisply worded entry didn’t quite do justice to its subject’s legacy. That humdrum phrase—“channel capacity”—refers to the maximum rate at which data can travel through a given medium without losing integrity. The Shannon limit, as it came to be known, is different for telephone wires than for fibre-optic cables, and, like absolute zero or the speed of light, it is devilishly hard to reach in the real world. But providing a means to compute this limit was perhaps the lesser of Shannon’s great breakthroughs. First and foremost, he introduced the notion that information could be quantified at all.

Read more at The New Yorker

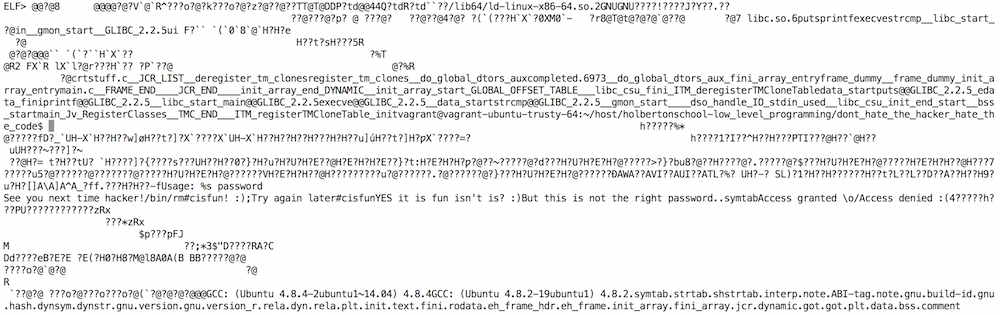

4 Ways a Password Could be Hacked Using Common Linux Tools

If you develop software in C (or any other language), you should know that using the strcmp function (or the equivalent in other languages) for password validation leaves the password and the program open to compromise. For those unfamiliar with this function, strcmp takes two parameters that contain a string and compares the two to see if they are the same. When used to validate a password, it exposes both the password and the program to compromise. If the source string is hard-coded in the program, it is viewable in plain text by opening it in any text editor. Sure, the password is wrapped in lots of unreadable code, and the average person wouldn’t know what they are looking at if they were staring right at it. However, it is not likely an average user that will attempt to hack a program. Here are four ways that the password could be hacked using tools readily available on Linux-based systems. The example program was written in C and compiled using gcc.

strings

Strings is a Linux-based tool that writes every string of printable text from within a binary file to the standard output.

Remember how I said the password was wrapped in unreadable code? Strings will strip all of that out leaving you with just the plain text data from the file. If that is too much data, use option d on strings to filter down to just the initialized, loaded data. which reduces 93 options for the stored password down to 24. From there a simple bash for loop can brute force the program to determine the password. Just like that the program is hacked in under two seconds. To try this out for yourself, grab the bash script from my Github and the a.out file from the Holberton School Github.

objdump

Linux’s objdump tool displays information from an object or program including functions and read-only data.

Using a list of strings from the code is a pretty rudimentary method to hacking a C program, and simply locking access for too many incorrect passwords would delay getting hacked a bit. The objdump allows access to track down what strings are actually being used in the strcmp function. There are two flags that simplify the data in a C program. Option d disassembles the data to make it more accessible. Option j enables selection of specific data for review. The first command I ran was “objdump -d -j.text a.out”. It displays the actual functions occurring including the main function. The yellow highlighted text shows the strcmp function being called twice in main. Two lines above the call is where the program moves the password string from memory into the register %esi. This register is used as a function parameter in strcmp. So to find the actual strings I move to .rodata, or read only data noting the memory locations where the parameter is sourced for each call.

The command to access the read-only data is very similar, “objdump -d -j.rodata a.out”. This displays memory locations with data showing in hexadecimal format. The ASCII characters are displayed to the right. Each piece of data is separated by a ’00’ null value. The needed data begins at the memory location listed in the main function and ends at the next null value. I’ve highlighted the test strings in the image above. Using the objdump tool I have now limited the number of test strings down to two. A lockout feature would no longer prevent the hacking of the program as the hacker would have a 50/50 chance of getting it right on the first try.

ltrace

The ltrace tool in Linux runs the program and listens for library function calls including strcmp and outputs the information to the standard output.

Perhaps the objdump tool is too complex. Another tool gives the same data as objdump with much easier access. The ltrace tool filters out all the data and isolates library function calls such as the strcmp function. The ‘e’ optional argument can filter down to a specific library function call. One run through ltrace and the program spills all the beans. Why bother hacking when the program will do it for you? The command used in this example is “ltrace -e strcmp ./a.out 1234”. The key difference here is that even if the password is not hard-coded it can still be obtained when strcmp uses it as a parameter.

gdb

Gdb, a debugging tool in Linux, is used by developers to stop a program in process and obtain troubleshooting information including data and functions called.

If the first three tools were not enough reason to not use strcmp for password validation, gdb, a common debugging tool, can be used to to find passwords validated with strcmp as well. The command used in this example is “gdb –args a.out 1234”. Once gdb is launched, “disass main” will breakdown the main function. The output is similar to what objdump displays after disassembly. The information needed is the memory location of each function call. This is used to create breakpoints to stop the program for review of data and processes in use. At each breakpoint, print the data stored in the register %esi using x/s. As mentioned earlier this is the register used by the strcmp function as a parameter. It holds the data that the entered password is compared against to gain access.

Once you have the data needed, you can quit the process to prevent the program from completing any other functions. The example program deletes itself if the wrong password is entered. Quitting gdb in this case prevents the remove command from running, and allows a hacker to proceed with accessing the program unhindered.

In summary, the use of strcmp to compare two strings for password validation is not a safe way to protect a program within C. The stored password is accessible in plain text within the compiled program. Accessing the stored password is made even easier when using tools such as strings, objdump, ltrace, and gdb. If you are aware of C programs currently using the strcmp function for password validation, share this post with the software engineer responsible for its development.

About Rick Harris

Rick Harris is a student at Holberton School, a project-based, peer-learning school developing full-stack software engineers. He has been involved in the IT industry for 6+ years most recently as a part of the Office of Information Technologies at the University of Notre Dame. Follow him on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Cracking a Simple Passworded File: A Beginner’s Guide to Security

Digital security has become very important in the past few years, with so much software being hacked everyday. This new trend has called attention to the need for better security with additional layers. This article is a beginner’s guide to know how a simple file coded with c language, secured with a password, can be hacked. I will be running Ubuntu 14.04 LTS for the enitirety of this tutorial. All the files used in this tutorial can be found on Github.

Lets start with running the file to see what it does:

$ ./crackme2

Access Denied

If you have been following my previous blog posts, the files used to show “usage” as to where we should write the password to get access; but this time things are a little bit different and we don’t even know where to write the password. Anyway, let’s run the file command to check if our file is stripped or not.

The file command determines the filetype. Three sets of tests are performed in this order: filesystem tests, magic number tests, and language tests.

$ file crackme2

crackme2: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86–64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.24, BuildID[sha1]=e06e0b0229279a69506925702a7f79e36bdc3eb2, not stripped

Luckily, it’s not stripped, which means our file still contains symbols. Lets start with doing an ltrace on this file.

ltrace is a program that simply runs the specified command until it exits. It intercepts and records the dynamic library calls which are called by the executed process and the signals which are received by that process. It can also intercept and print the system calls executed by the program.

$ ltrace ./crackme2

__libc_start_main(0x40087d, 1, 0x7ffc72840328, 0x400a70 <unfinished …>

strncmp("XDG_SESSION_ID=4", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 8

strncmp("TERM=xterm", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 4

strncmp("SHELL=/bin/bash", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 3

strncmp("SSH_CLIENT=10.0.2.2 23512 22", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 3

strncmp("OLDPWD=/home/vagrant/github/holb"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -1

strncmp("SSH_TTY=/dev/pts/0", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 3

strncmp("USER=vagrant", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 5

strncmp("LS_COLORS=rs=0:di=01;34:ln=01;36"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -4

strncmp("MAIL=/var/mail/vagrant", "Passw0rd=", 9) = -3

strncmp("PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -32

strncmp("PWD=/home/vagrant/github/holbert"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -10

strncmp("LANG=en_US.UTF-8", "Passw0rd=", 9) = -4

strncmp("NODE_PATH=/usr/lib/nodejs:/usr/l"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -2

strncmp("SHLVL=1", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 3

strncmp("HOME=/home/vagrant", "Passw0rd=", 9) = -8

strncmp("passwOrd=bilal", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 32

strncmp("LOGNAME=vagrant", "Passw0rd=", 9) = -4

strncmp("SSH_CONNECTION=10.0.2.2 23512 10"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = 3

strncmp("LESSOPEN=| /usr/bin/lesspipe %s", "Passw0rd=", 9) = -4

strncmp("XDG_RUNTIME_DIR=/run/user/1000", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 8

strncmp("LESSCLOSE=/usr/bin/lesspipe %s %"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -4

strncmp("_=/usr/bin/ltrace", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 15

puts("Access Denied"Access Denied

) = 14

+++ exited (status 1) +++

From the looks of it, this program is accessing all the environment variables such as $HOME, $PWD, and trying to compare first 9 characters with Passw0rd=. We can easily recognize that this binary file is trying to search for an environment variable by the name Passw0rd. Lets have one with a random value and do an ltrace again.

$ export Passw0rd=hey

$ ltrace ./crackme2

__libc_start_main(0x40087d, 1, 0x7fff93c86f38, 0x400a70 <unfinished …>

strncmp("XDG_SESSION_ID=4", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 8

strncmp("TERM=xterm", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 4

strncmp("SHELL=/bin/bash", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 3

strncmp("SSH_CLIENT=10.0.2.2 23512 22", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 3

strncmp("OLDPWD=/home/vagrant/github/holb"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -1

strncmp("SSH_TTY=/dev/pts/0", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 3

strncmp("passw0rd=bilal", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 32

strncmp("USER=vagrant", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 5

strncmp("LS_COLORS=rs=0:di=01;34:ln=01;36"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -4

strncmp("MAIL=/var/mail/vagrant", "Passw0rd=", 9) = -3

strncmp("PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -32

strncmp("PWD=/home/vagrant/github/holbert"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -10

strncmp("LANG=en_US.UTF-8", "Passw0rd=", 9) = -4

strncmp("NODE_PATH=/usr/lib/nodejs:/usr/l"…, "Passw0rd=", 9) = -2

strncmp("SHLVL=1", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 3

strncmp("HOME=/home/vagrant", "Passw0rd=", 9) = -8

strncmp("Passw0rd=hey", "Passw0rd=", 9) = 0

MD5_Init(0x7fff93c86da0, 0x400b06, 9, 6) = 1

strlen("hey") = 3

MD5_Update(0x7fff93c86da0, 0x7fff93c88f2c, 3, 0x7fff93c88f2c) = 1

MD5_Final(0x7fff93c86e00, 0x7fff93c86da0, 0x7fff93c86da0, 6) = 1

sprintf("60", "%02x", 0x60) = 2

sprintf("57", "%02x", 0x57) = 2

sprintf("f1", "%02x", 0xf1) = 2

sprintf("3c", "%02x", 0x3c) = 2

sprintf("49", "%02x", 0x49) = 2

sprintf("6e", "%02x", 0x6e) = 2

sprintf("cf", "%02x", 0xcf) = 2

sprintf("7f", "%02x", 0x7f) = 2

sprintf("d7", "%02x", 0xd7) = 2

sprintf("77", "%02x", 0x77) = 2

sprintf("ce", "%02x", 0xce) = 2

sprintf("b9", "%02x", 0xb9) = 2

sprintf("e7", "%02x", 0xe7) = 2

sprintf("9a", "%02x", 0x9a) = 2

sprintf("e2", "%02x", 0xe2) = 2

sprintf("85", "%02x", 0x85) = 2

strcmp("d8578edf8458ce06fbc5bb76a58c5ca4"…, "6057f13c496ecf7fd777ceb9e79ae285"…) = 46

puts("Access Denied"Access Denied

) = 14

+++ exited (status 1) +++

Woa! This opened a whole new door for us. So after finding out the Passw0rd environment variable, it gets the string length for the value of that environment variable, and from the looks of it calculates an MD5 hash and compares it with a predefined md5 hash in the program.

Let’s convert our input password to an MD5 hash to confirm it. Just a simple google search would land you with so many md5 hash calculators, you can even do it using bash:

$ printf "hey" | md5sum | cut -d' ' -f1

6057f13c496ecf7fd777ceb9e79ae285

So this MD5 hash is exactly what you can see in the ltrace output for our input password, and it is comparing it with a predefined md5 hash, d8578edf8458ce06fbc5bb76a58c5ca4, using strcmp. Now we need some way to reverse this to a string.

It is not possible to retrieve the original string from a given MD5 hash using only mathematical operations, but there is a way to decrypt a MD5 hash, using a dictionary populated with strings and their MD5 equivalent (or we can try brute forcing as well). As most users use very simple passwords (like “123456”, “password”, “abc123”, etc), MD5 dictionaries make them very easy to convert them back to a string. MD5 reverse dictionary having several millions of entries can be used to convert an MD5 hash to a string.

Let’s use this website and try converting this hash to a string. It results in an output of “qwerty”. Lets try our luck with this password.

$ export Passw0rd=qwerty

$ ./crackme2

Access Granted

Tada! We finally have the password and we didn’t even need tools like gdb for it.

Taking it one step further, we can write a simple ruby script containing only lowercase alphabets to try to brute-force the MD5 string. This script assumes the password string contains only lower-case letters.

#!/usr/bin/ruby

require 'digest/md5'

?a.upto('zzzzzzz') { |string|

md5=Digest::MD5.hexdigest(string)

puts "Trying: #{string}"

if md5 == "d8578edf8458ce06fbc5bb76a58c5ca4"

puts "nThe string is #{string}n"

exit

end

}

Run this script, and then go watch a movie or sleep. After quite a bit of time, this script will tell us that the string for that specific MD5 hash is “qwerty”.

P.S. We can also use an equivalent bash script for brute forcing, but as it turns out it was too slow. I have uploaded the bash brute force script in my github repo as well in the link given above.

This article was contributed by a student at Holberton School and should be used for educational purposes only.

Demystifying Containers for a Better DevOps Experience

Working with containers in the enterprise often can seem daunting to a business which has no experience with them. Developers and DevOps teams alike can benefit from implementing containers into their infrastructure and pipeline, as a solid container-based development workflow not only allows for flexible and agile application development but with testing, staging, and bug fixes. Containers have seen a variety of improvements in the last year including better container visibility, enhanced log management, improved security, and a focus on scalability.

Whether working with Kubernetes pods, Docker Swarm, or Mesos, choosing the correct container solution will ultimately depend on the scale, infrastructure, and availability needs of one’s organization. Mesos and Docker have both addressed scale, with both Mesos and Docker able to scale out easily.

Read more at Forbes

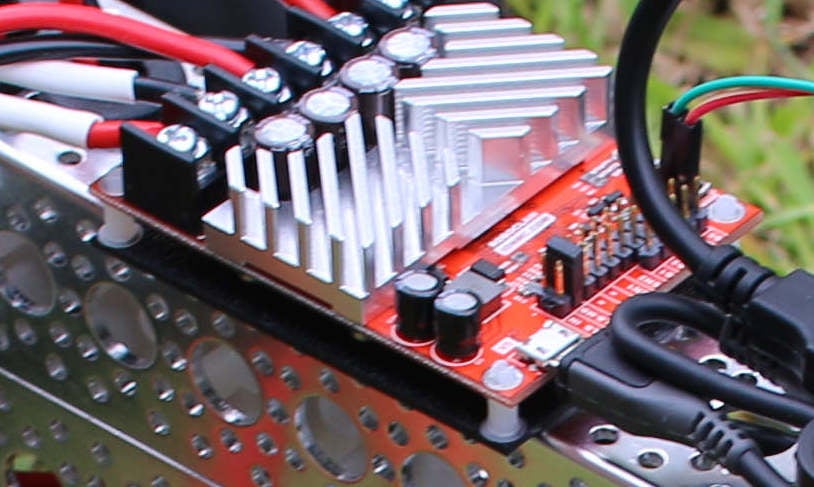

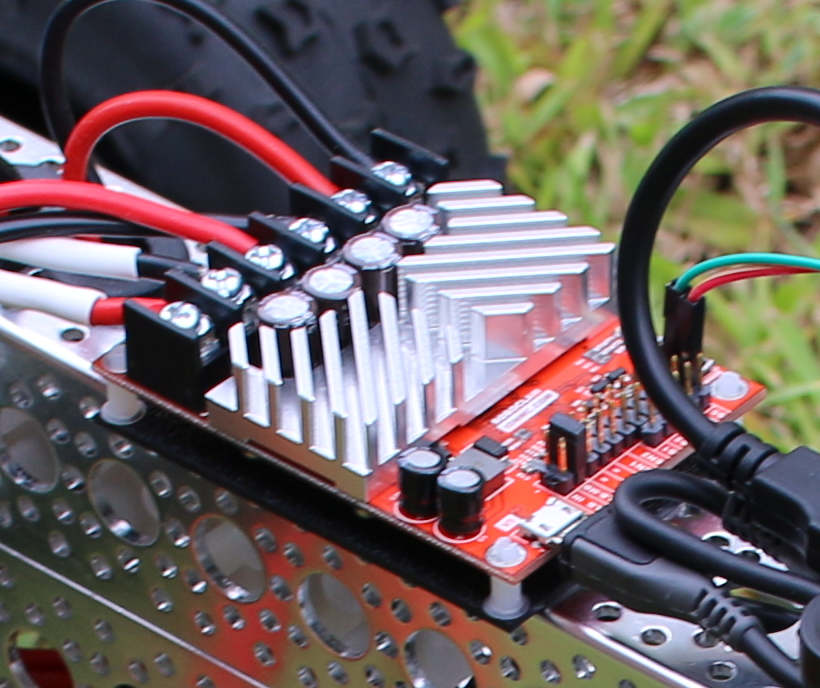

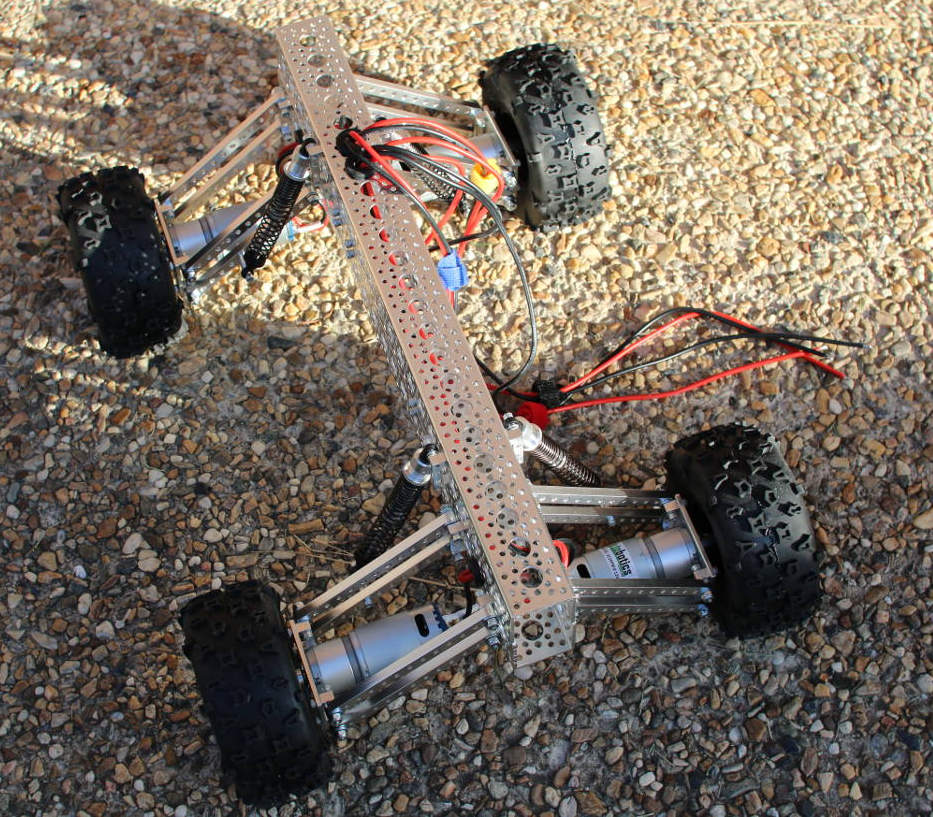

Build an Off-Road Raspberry Pi Robot: Part 1

Take your Raspberry Pi into the wild with the Mantis robot kit. In this series of articles, I’ll discuss the process of building, powering, connecting, and controlling your own Mantis robot, and I’ll also point out some potential pitfalls.

The Mantis is available in four– and six-wheel configurations and includes an electric motor to drive each wheel with potentially a little over 2 foot-pounds of torque. Generating such torque allows the Mantis to run over uneven terrain, such as loose rocks, small logs, and other obstacles, and climb some reasonable hills.

Although there are general purpose headers on the Raspberry Pi to allow you to communicate with other hardware, you can’t run large electric motors directly from those headers. Motors want higher voltages than the Raspberry Pi can directly supply and will draw far more current than the Raspberry Pi can directly provide.

As mentioned in a previous article, you will want to use a motor controller chip or board to interface with electric motors. The motors on the Mantis are rated to draw up to 20 amps of power each. So, I will use a RoboClaw motor controller board that is rated to deliver up to 45 amps per channel in this article (Figure 3).

To run a Linux machine on a robot, you probably want to obtain a stable power supply from a battery, and will likely want to talk to your Raspberry Pi through a WiFi adapter. Other input and output, such as how to control the speed and direction of the robot and being able to see how much battery power remains, call for some form of wireless connection.

The RoboClaw includes a Battery Eliminator Circuit (BEC) that lets you to run the entire robot from a single battery. A large battery that can handle the current draw of the motors is attached to the RoboClaw. This single battery will usually be a two- or three-cell LiPo battery that will run at 7.4 or 11.1 volts. The actual voltage from the battery will change over time as you draw power from the battery, and it discharges. The BEC on the 45A RoboClaw controller offers up to 3 amps at a stable 5 volts which is fine to run the Raspberry Pi.

The only difficulty here is that the BEC on the RoboClaw uses dupont headers, much like the connecting cables on breadboards, while the Raspberry Pi wants to draw its power from a microUSB cable. I opted to create my own custom cable by wiring the positive and negative pins of a microUSB cable to half of a breadboard cable.

For each motor on the Mantis to generate its maximum torque, it might want to use 20 amps of current. You should have a battery that can deliver at least 80 or 120 amps of current depending whether you have the four- or six-wheel Mantis. If you are running the motors on 10 volts, then you might potentially draw over 1 kilowatt of power. It is good to know the worst case power draw for the motors on a robot so you can work out the battery requirements, and what cabling you want to use to connect to the motors so that the system does not burn up cables or suffer a catastrophic battery failure. The latter can occur if you try to draw more current from a battery than it is rated to deliver. High power batteries can also fail if they have been charged incorrectly or physically damaged. Be sure to familiarize yourself with the procedures for safely using your batteries.

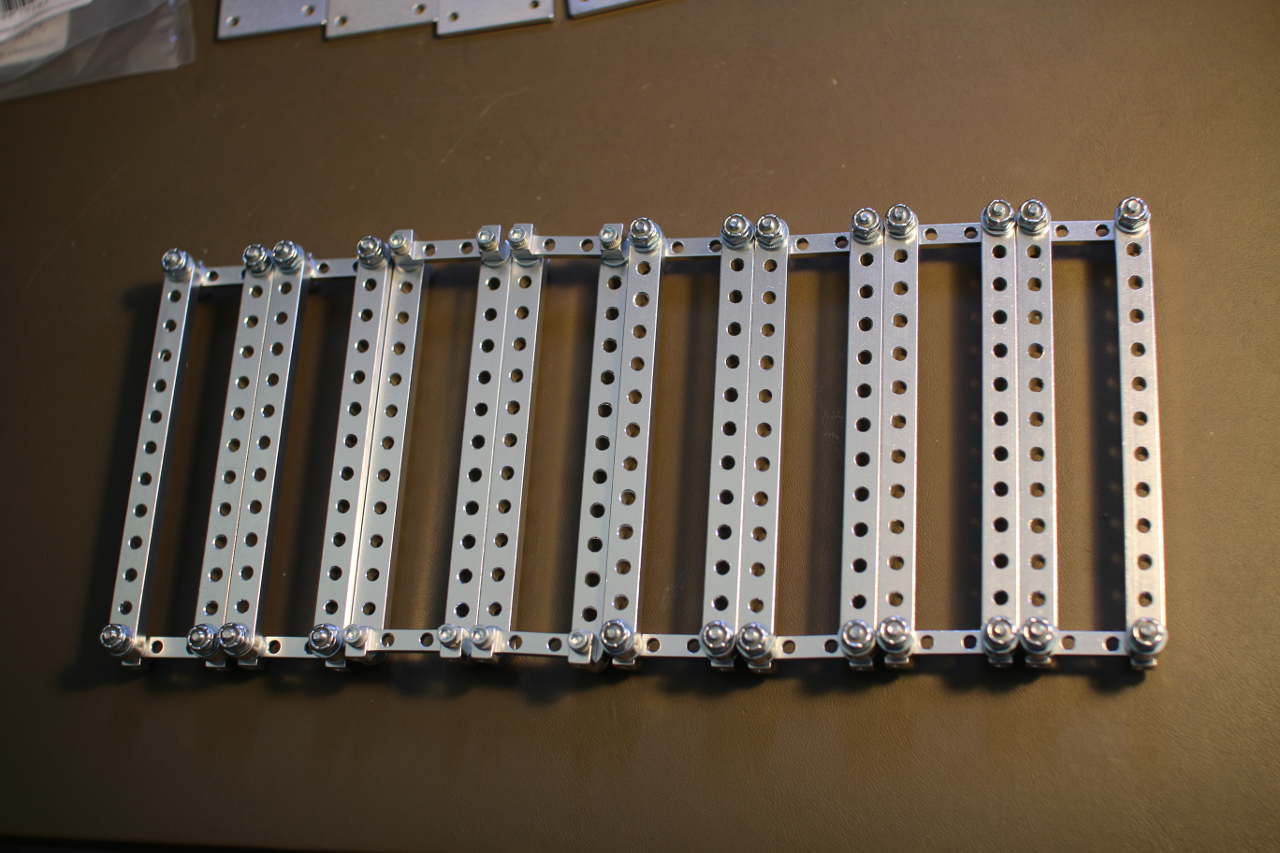

Building the Mantis

ServoCity has an assembly video on YouTube showing how to put the Mantis kit together. I soldered silicon-coated wire to the motors before mounting them to the Mantis and routed the wires through to the top of the Mantis before securing the top channel to the bottom channel. Each motor mount has four beams that attach back to the main channel. Two of each of these beams have a “90 Degree Dual Side Mount D” at each end of it. Given the number items to connect, having a ratchet that can handle the 6-32 locknuts will make these all go together much more quickly.

Next Time

In the next article, I’ll show how to attach the motors, connect the RoboClaw to your Raspberry Pi through a USB port, and supply the RoboClaw with its own power source to talk to the Pi over USB.

Read Part 2 here.

Distributed Tracing — The Most Wanted and Missed Tool in the Microservice World

We, as engineers, always wanted to simplify and automate things. This is something in our nature. That’s how our brains work. That’s how procedural programming was born. After some time, the next level of evolution was object oriented programming.

The idea was always the same. Take something big and try to split it into isolated abstractions with hidden implementations. It is much easier to think about complex system using abstractions. It is way more efficient to develop isolated blocks.

The way we did system architecture design was evolving too…

Read more at Init.ai Decoded

The First Five Linux Command-Line Apps Every Admin Should Learn

Linux has taken over the enterprise. It runs the backbone for many of the largest companies. It’s one of the biggest players in big data. If you’re serious about moving up the IT ladder, at some point, you’re going to have to know Linux.

And although the Linux GUI tools are now as good as those available for any other platform, some tasks will require a bit of command-line knowledge. But where do you begin? You start off where every Linux newbie should… with what I believe are five of the most important commands for new Linux admins to learn.

Read more at TechRepublic