Who wrote this code? Why? What changes led to this function’s current implementation?

These are typical questions that developers (and sometimes lawyers) ask during their work. Most software development projects use version control software (such as Git or Subversion) to track changes and use the “blame” feature of these systems to answer these questions.

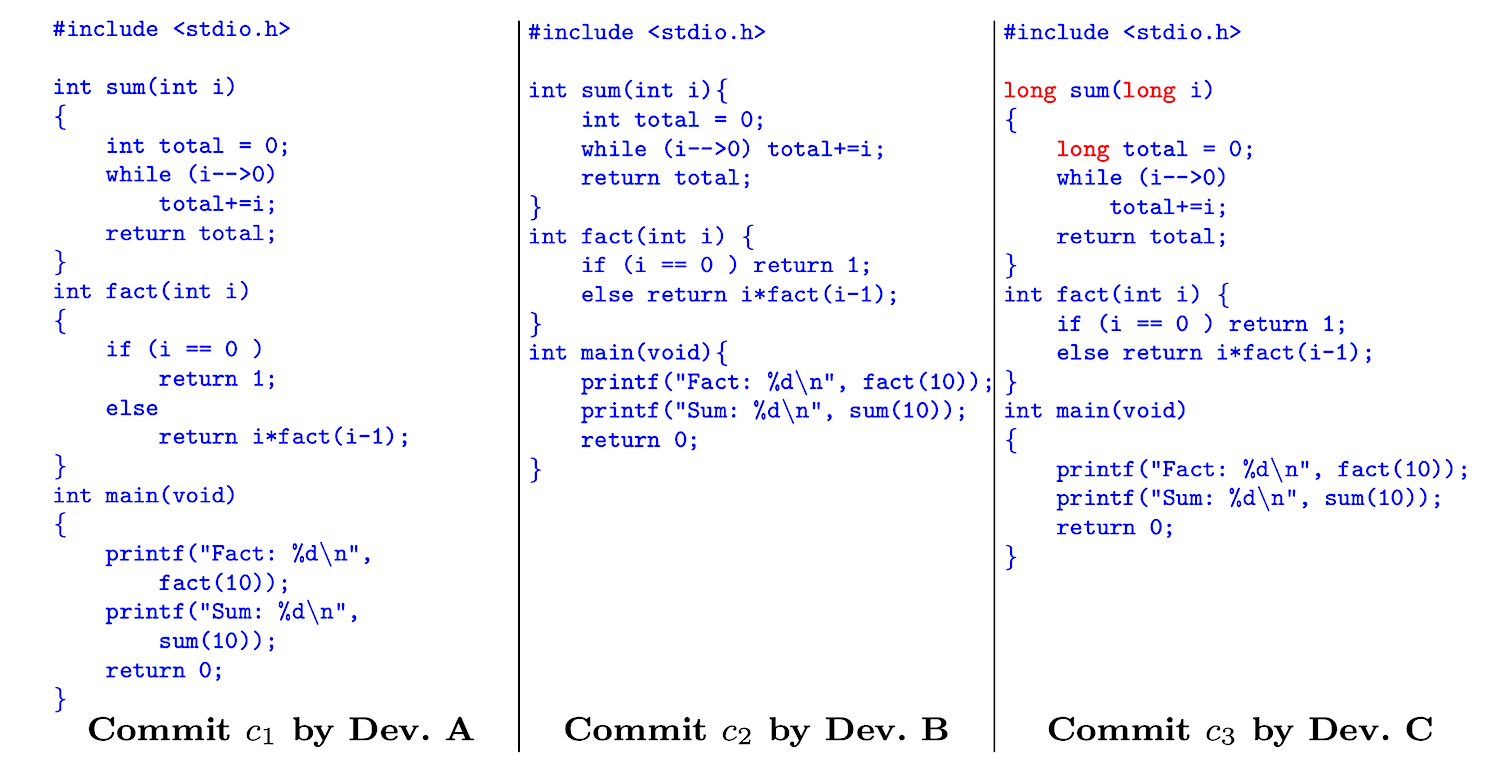

Unfortunately, version control systems are only capable of tracking full lines of code. Imagine the following scenario: A simple file is created by developer A; later, it is changed by Developer B, and finally, by Developer C. The following figure depicts the contents of the files after each modification. The source code has been colored according to the developer who introduced it (blue for Developer A, green for Developer B, and red for Developer C; note that Developer B only changed whitespace –including merging some lines).

Blame tracks lines not tokens

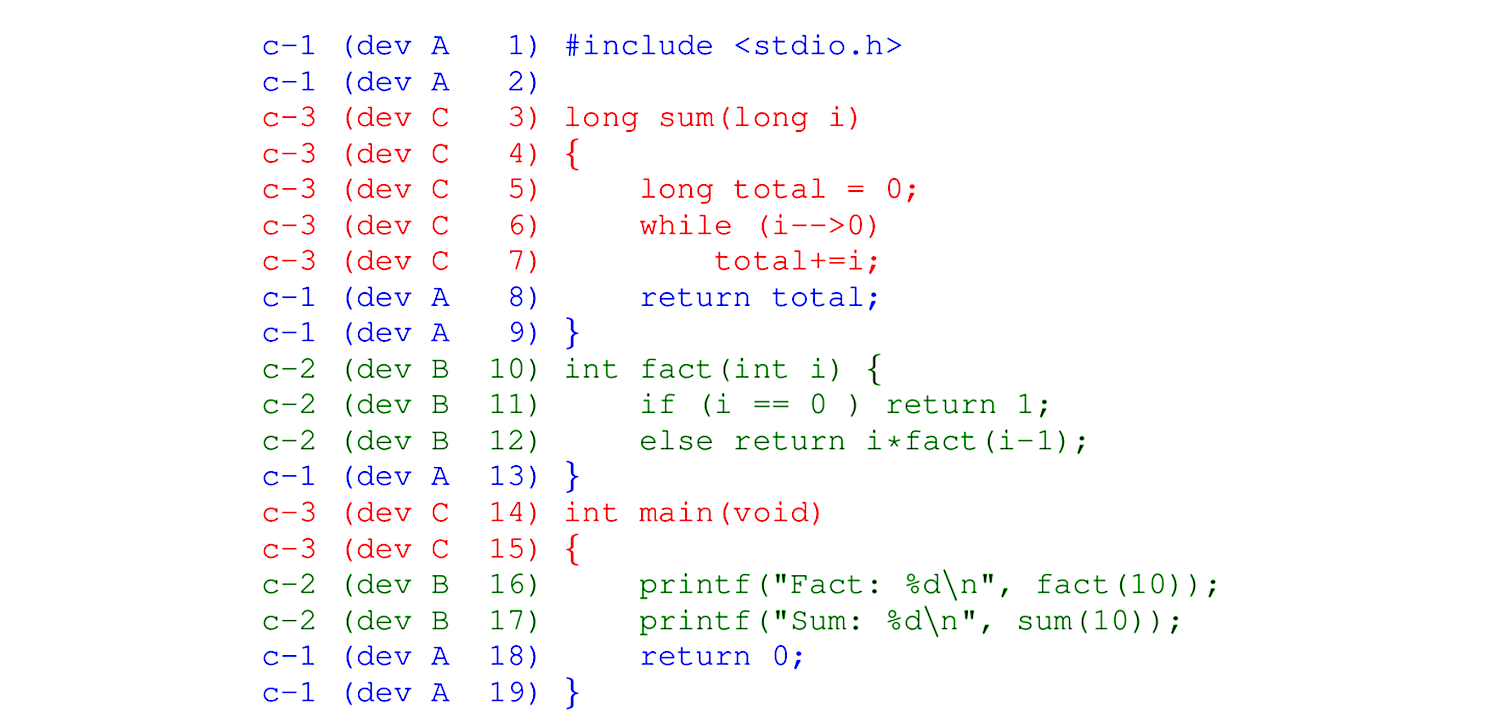

If we were to use git to track these changes, and use git-blame with default parameters, its output will show that Developer B and C are mostly responsible for the contents of the file. However, if we were to instruct blame to ignore changes to whitespace, the results would be:

In general, one would expect to always ask blame to ignore whitespace. Unfortunately, this is not always possible (such as the “blame” view of GitHub, which is computed without ignoring whitespace).

Note that, even if we run blame with the ignore-whitespace option, the “blame” is incorrect. First, lines merged or split are not addressed properly by blame (the ignore-whitespace option does not ignore them). Second, lines that were mostly authored by Developer A are now assigned to Developer C because she was the last one to modify them.

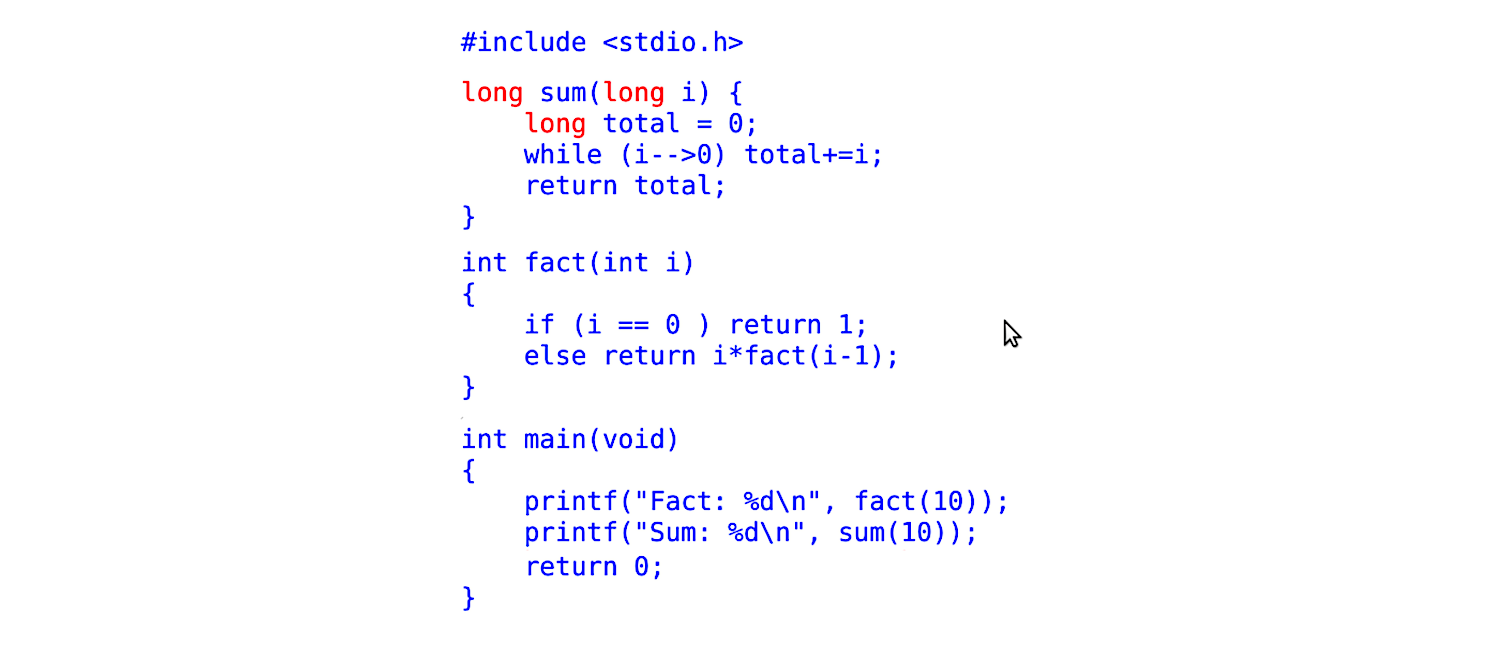

If we consider the token as the indivisible unit of source code (i.e., a token cannot be modified, it can only be removed or inserted), then what we really want is to know who is responsible for introducing each token to the source code base. A blame-per-token for the file in our example would look like the figure below. Note how it correctly shows that the only changes made by C to the source code were the replacement of int with long in three places, and that B made no changes to the code:

cregit: improving blame of source code

We created cregit to do exactly this. The goal of cregit is to provide token-level blame for a software system whose history has been recorded using git. The details of cregit’s implementation can be found in this Working Paper (currently under review).

We have empirically evaluated cregit on several mature software systems. In our experiments, we found that blame-per-line tends to be accurate between 70% and 80% of the time. This highly depends on how much the code has been modified. The more modifications to existing code, the less likely that blame-per-line will be accurate. Cregit on the other hand is able to increase this accuracy to 95% (please see the paper mentioned above for details).

For the last two years, we have been running cregit on the source code of the Linux kernel. The results can be found at: https://cregit.linuxsources.org/code/4.19/.

Blame-per-line is easy to implement, just put the blame information to the side; however, blame-per-token is significantly more complex, as its tokens might have different authors and/or commits responsible for them. Hence, we are currently rolling out an improved view of blame-per-token for kernel release 4.19 of Linux (older versions use an old view, and most of the information here does not apply).

cregit views: inspecting who changed what/when

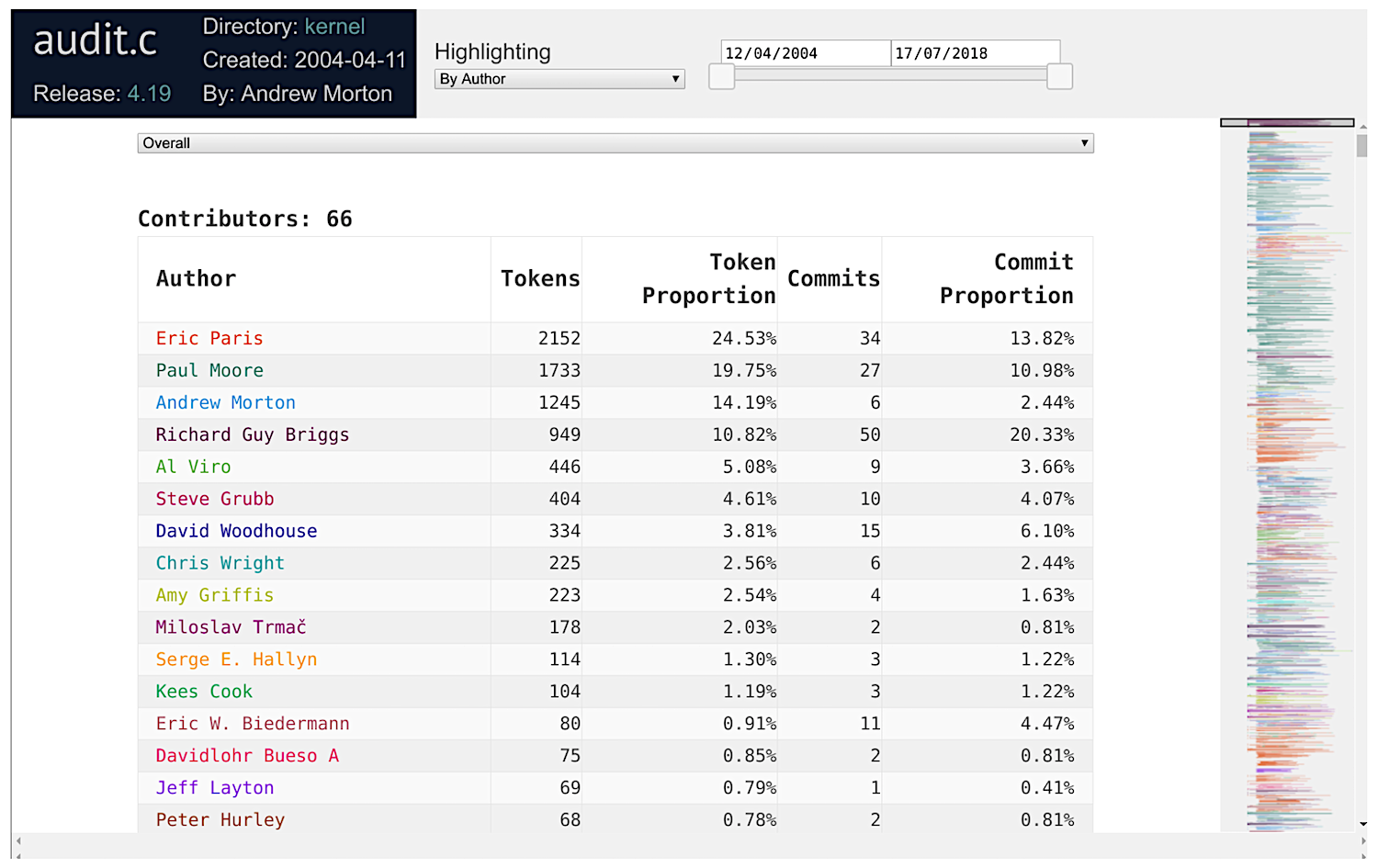

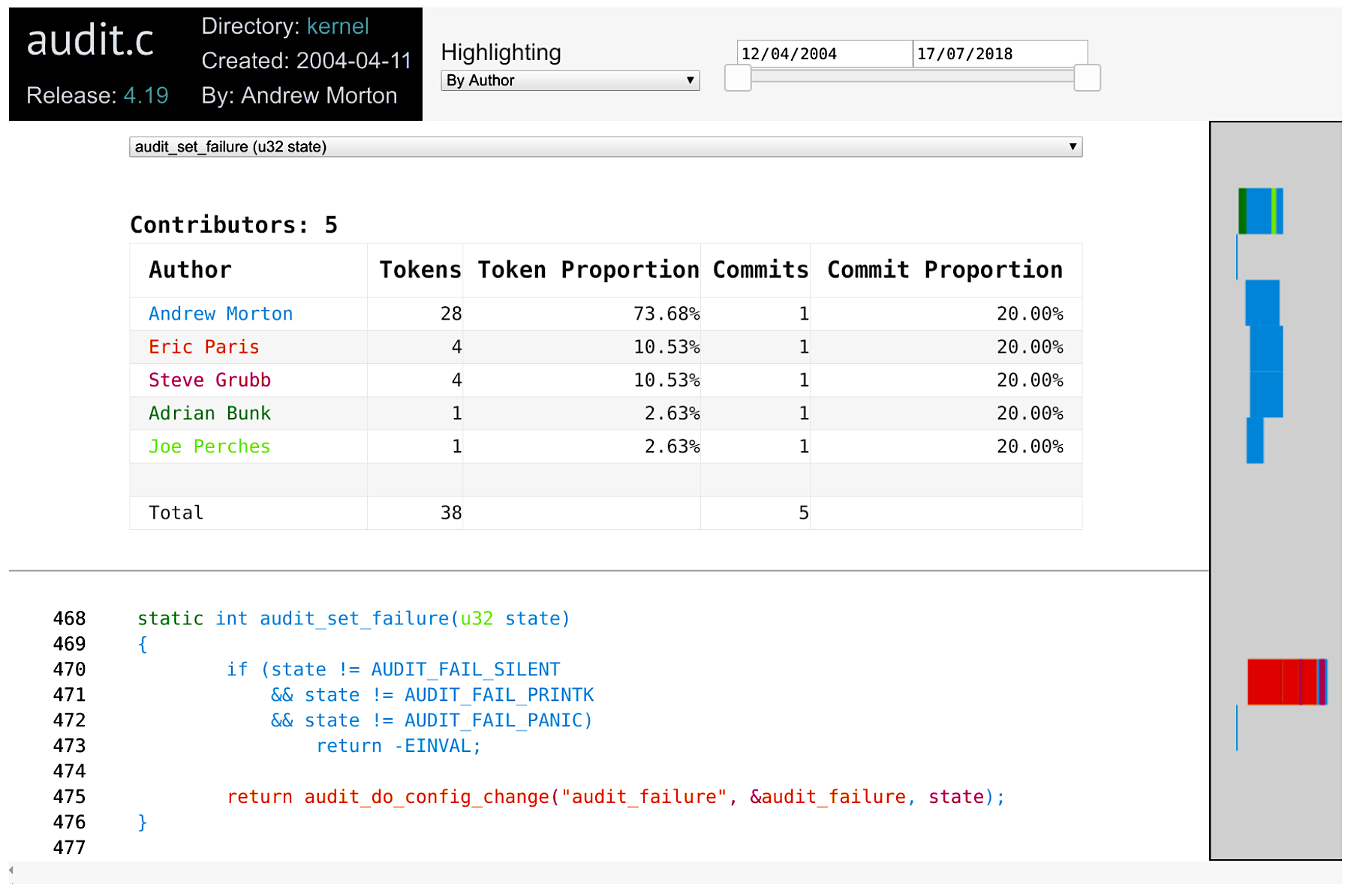

Below is an example of the blame-per-token views of Linux 4.19, specifically for the file audit.c.html.

The top part gives us an overview of who the authors of the file are. The first 50 authors are individually colored. The source code is colored according to the person who last added the token. The right-hand side of the view shows an overview of the “ownership” of the source code.

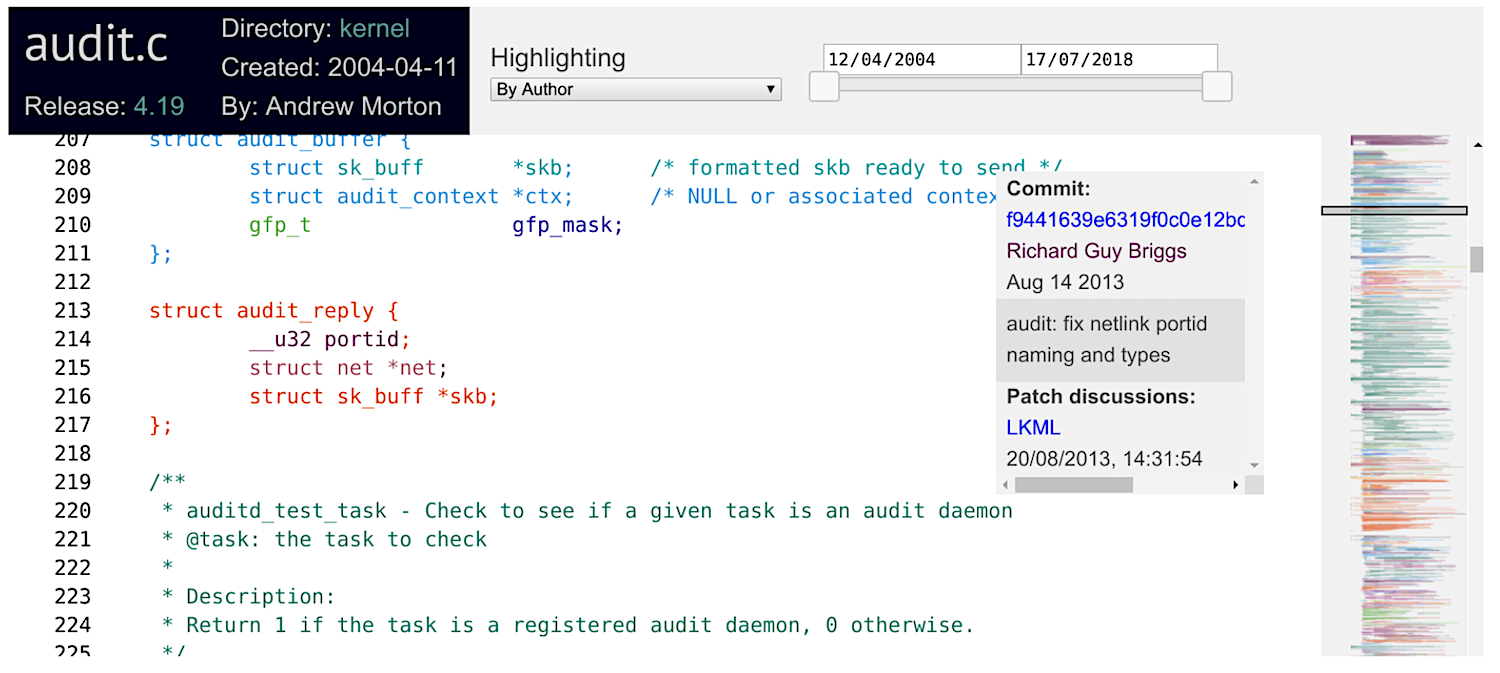

While hovering over the source code, you will see a box displaying information about how that token got into the source code: the commit id, its author, and its commit timestamp and summary. If you click on the token, this information is enhanced with a link to the email thread that corresponds to the code review of the commit that inserted that token, as shown below:

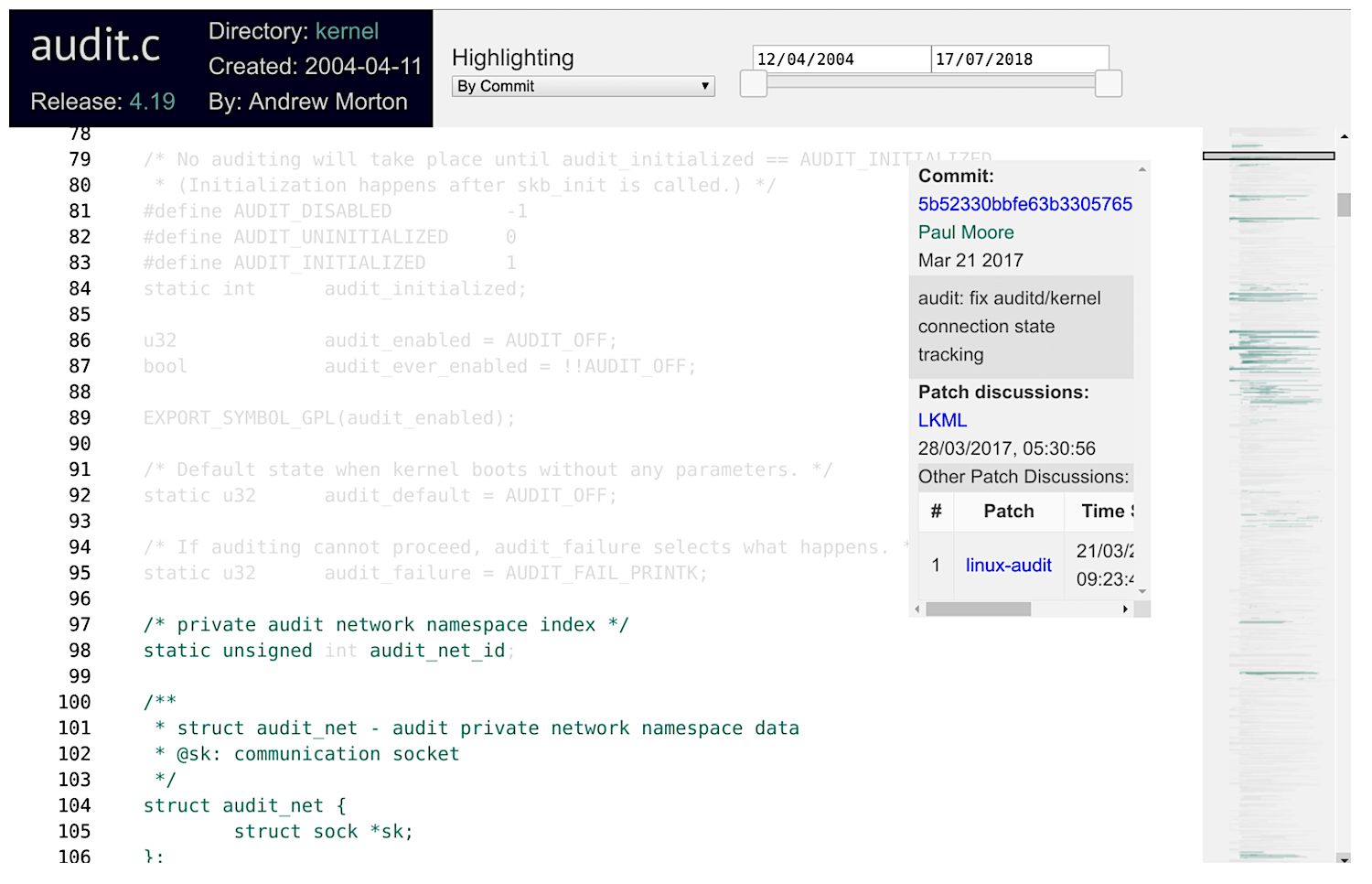

The views are highly interactive. For example, one can select to highlight a commit (top middle combo box). In this case, all the code is grayed out, except for the tokens that were added by that commit, as shown below.

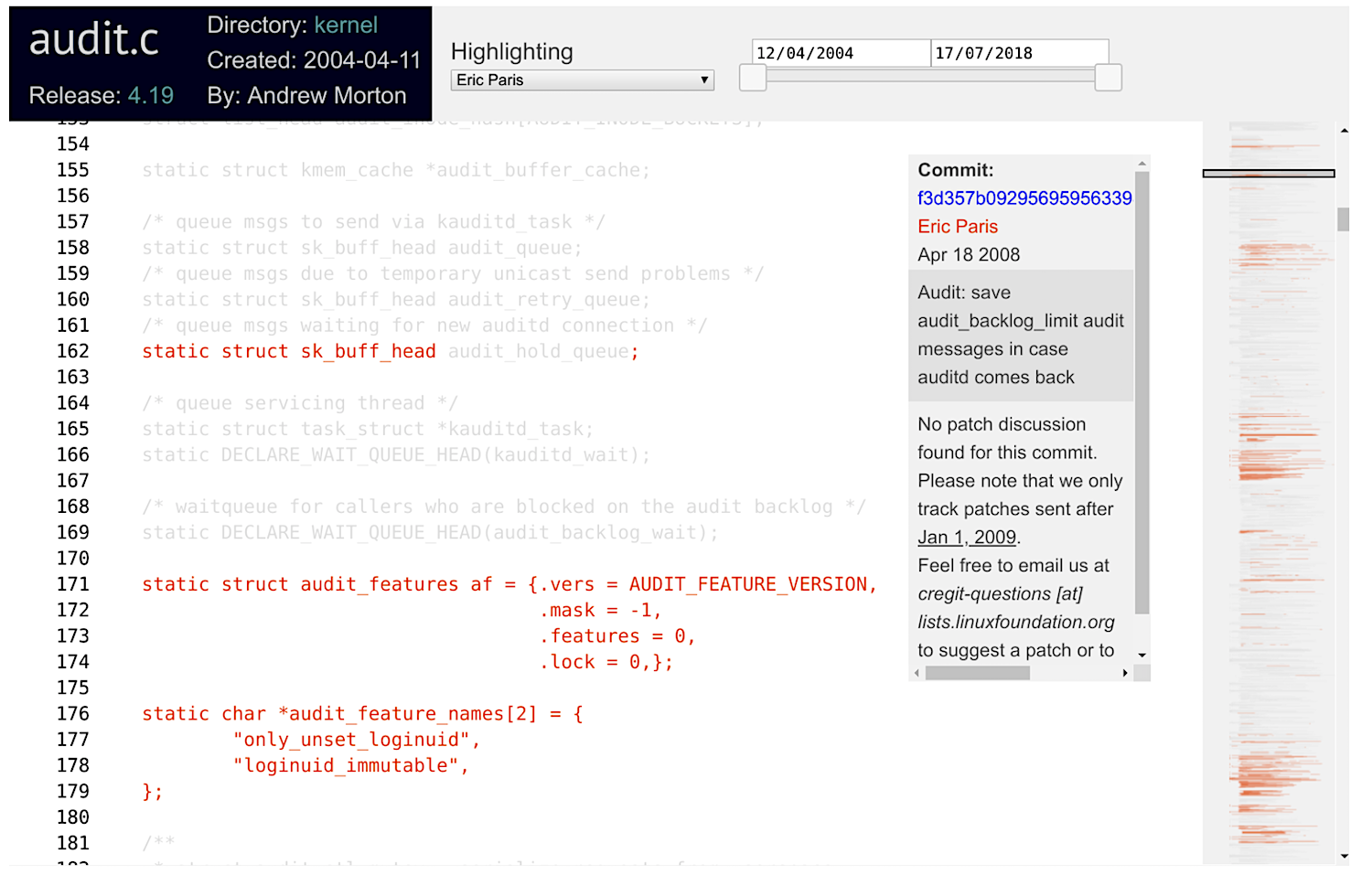

You can also click on an author’s name, and only that author’s code will be highlighted. For example, in the image below I have highlighted Eric Paris’s contributions.

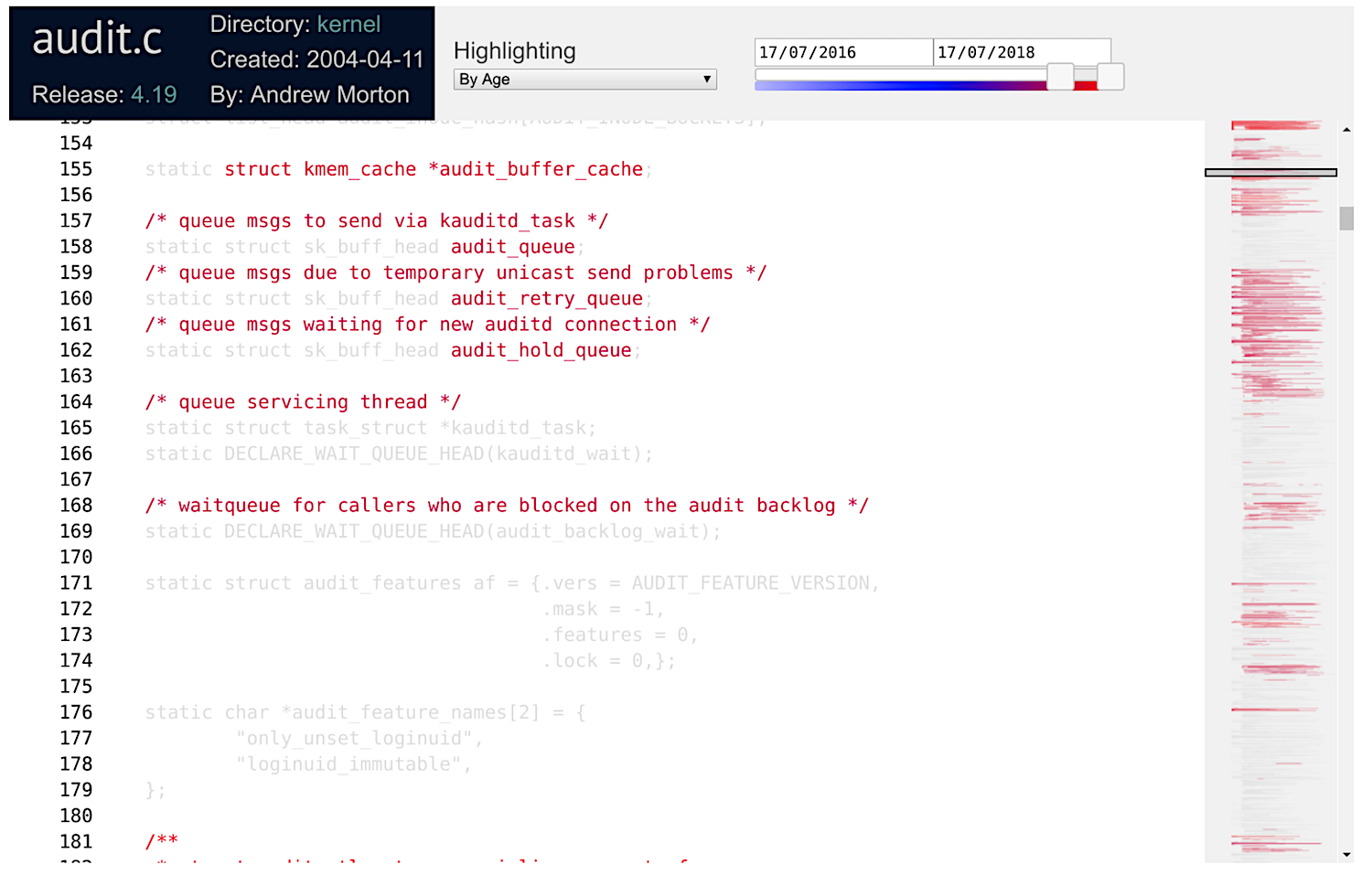

cregit is also capable of highlighting the age of the code. The sliding bar at the top right allows to narrow the period of interest. Below I have selected to show changes during the last two years (note that the file was last modified in July 17, 2018.

It is also possible to focus on a specific function, which can be selected with the Functions combo box at the top of the source code. In the example below I have selected the function audit_set_failure. The rest of the code has been hidden.

These features can be easily combined. You can select the age of the code by a specific author. And narrow it to a given function!

cregit views: improving the linkage of email code reviews

We are going to keep expanding the information shown in the commit panel. Currently, in addition to the metadata of the commit that is responsible for the token, it provides hyperlinks to the commit patch, and to any email discussions we have been able to find regarding this commit. We are working to match more and more commits.

cregit: where to get it

cregit is open source, and is accessible from https://github.com/cregit/cregit. It is capable of processing C, C++, Java, and go. We can probably add support for perl and python fairly easily. All we need to support a new language is a tokenizer.

cregit’s input is a git repository, and its output is another git repository that tracks the source code by token (see paper for details). From this repository we construct the blame views shown above. If you are interested to have your repository processed with cregit, email me.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge several people for their contributions:

- Bram Adams. Bram and I are the creators of cregit.

- Jason Lim. As part of his coursework at UVic he implemented the new cregit views, which have greatly improved their usefulness.

- Alex Courouble. As part of his master’s at the Poly of Montreal he implemented the matching algorithms of commits to email discussions, based on earlier work of Yujuan Jiang during her PhD.

- Kate Stewart. She has been instrumental to gather user requirements and to evaluate cregit and its views.

- Isabella Ferreira. She is picking up where Alex left and continues to improve the matching of commits to emails.

This article was written by Daniel German (dmg@turingmachine.org) and originally appeared on GitHub.