We’re going to look at some IPv6 calculators, sipcalc and subnetcalc, and some tricks for subnetting without breaking our brains. Let’s start with reviewing IPv6 address types. There are three types: unicast, multicast, and anycast.

IPv6 Unicast

The unicast address is a single address identifying a single interface. In other words, what we usually think of as our host address. There are three types of unicast addresses:

- Global unicast are unique publicly routable addresses. These are controlled by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), just like IPv4 addresses. These are the address blocks you get from your Internet service provider. These are in the 2000::/3 range, minus a few exceptions listed in the table at the above link.

- Link-local addresses use the fe80::/10 address block and are similar to the private address classes in IPv4 (10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, 192.168.0.0/16). Some major differences are link-local addresses are not routable, but are confined to a single network segment. They are automatically derived from the MAC address of the network interface; this is not a guarantee that all of them are unique, but your odds are pretty good that they are. The IPv6 protocol requires that every network interface is automatically assigned a link-local address.

- Special addresses are loopback addresses, IPv4-address mapped spaces, and 6-to-4 addresses for crossing from an IPv4 network to an IPv6 network.

Multicast

Multicast in IPv6 is similar to the old IPv4 broadcast: a packet sent to a multicast address is delivered to every interface in a group. The IPv6 difference is that only hosts who are members of the multicast group receive the multicast packets, rather than all reachable hosts. IPv6 multicast is routable, and routers will not forward multicast packets unless there are members of the multicast groups to forward the packets to. Remember IPv4 broadcast storms? They’re much less likely to occur with IPv6. Multicast relies on UDP rather than TCP, so it is used for multimedia streaming, such as efficiently streaming the video feed from a single IP camera to multiple hosts. See IPv6 Multicast Address Space Registry for complete information.

Anycast

An anycast address is a single unicast address assigned to multiple nodes, and packets are received by the first available node. It is a cool mechanism to provide both load-balancing and automatic failover without a lot of hassle. There is no special anycast addressing scheme; all you do is assign the same address to multiple nodes. The root name servers use anycast addressing.

IPv6 Subnet Calculators

What I really really want is an IPv6 equivalent for ipcalc, which calculates multiple IPv4 subnets with ease. I have not found one.

There are other helpful tools for IPv6. ipv6calc performs all manner of useful queries and address manipulation. It does not include a subnet calculator, but it does tell you the subnet and host portions of an address:

$ ipv6calc -qi 2001:0db8:0000:0055:0000:0000:0000:0100

Address type: unicast, global-unicast, productive, iid, iid-local

Registry for address: reserved(RFC3849#4)

Address type has SLA: 0055

Interface identifier: 0000:0000:0000:0100

SLA stands for Site Level Aggregation, which means subnet. If you change 0055 to 0056 then you have a new subnet. The interface identifier is the portion that identifies a single network interface. Think of an IPv6 address as having three parts: the network address, which is the same for every node on your network, and the subnet and host addresses, which you control. (Network nerds use all kinds of cool terminology to say these things, but I prefer the simplified version.)

|---network---| |subnet| |---------host-------|

2001:0db8:0000 :0055 :0000:0000:0000:0100

IPv6 addresses are in hexadecimal, which is the 16 characters 0-9 and a-f. So, within the subnet and host blocks, you can use any numbers from 0000 to ffff. So even if you count on your fingers this isn’t too hard to figure out.

Having calculators helps check your work. (Free tip to documentation writers and anyone who wants to be helpful: examples of both correct and incorrect output are fabulously useful.) There are two IPv6 calculators that I use. subnetcalc is actively maintained, while sipcalc is not, though the maintainers accept patches and bugfixes. They work similarly, and present information in slightly different ways. Sometimes all you need is a different viewpoint.

Let’s say your ISP gives you 2001:db8:abcd::0/64. How many addresses is that?

$ subnetcalc 2001:db8:abcd::0/64

Address = 2001:db8:abcd::

2001 = 00100000 00000001

0db8 = 00001101 10111000

abcd = 10101011 11001101

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

Network = 2001:db8:abcd:: / 64

Netmask = ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff::

Wildcard Mask = ::ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff

Hosts Bits = 64

Max. Hosts = 18446744073709551616 (2^64 - 1)

Host Range = { 2001:db8:abcd::1 - 2001:db8:abcd:0:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff }

Properties =

- 2001:db8:abcd:: is a NETWORK address

[...]

18,446,744,073,709,551,616 addresses is probably enough. The Wildcard Mask shows the bits that define your host addresses. But maybe you want to divide this up a bit. There are 128 bits in an IPv6 address (8 quads x 16 bits), so let’s plug that into subnetcalc and see what happens:

$ subnetcalc 2001:db8:abcd::0/128

[...]

Network = 2001:db8:abcd:: / 128

Netmask = ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff

Wildcard Mask = ::

Hosts Bits = 0

Max. Hosts = 0 (2^0 - 1)

Host Range = { 2001:db8:abcd::1 - 2001:db8:abcd:: }

Zero hosts? That doesn’t sound good. sipcalc shows the same thing in a different way:

$ sipcalc 2001:db8:abcd::0/128

-[ipv6 : 2001:db8:abcd::0/128] - 0

[IPV6 INFO]

Expanded Address - 2001:0db8:abcd:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000

Compressed address - 2001:db8:abcd::

Subnet prefix (masked) - 2001:db8:abcd:0:0:0:0:0/128

Address ID (masked) - 0:0:0:0:0:0:0:0/128

Prefix address - ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff

Prefix length - 128

Address type - Aggregatable Global Unicast Addresses

Network range - 2001:0db8:abcd:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000 -

2001:0db8:abcd:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000

So we want something between /64 and /128.

$ subnetcalc 2001:db8:abcd::0/86 -n

Address = 2001:db8:abcd::

2001 = 00100000 00000001

0db8 = 00001101 10111000

abcd = 10101011 11001101

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

Network = 2001:db8:abcd:: / 86

Netmask = ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:fc00::

Wildcard Mask = ::3ff:ffff:ffff

Hosts Bits = 42

Max. Hosts = 4398046511103 (2^42 - 1)

Host Range = { 2001:db8:abcd::1 - 2001:db8:abcd::3ff:ffff:ffff }

Properties =

- 2001:db8:abcd:: is a NETWORK address

The -n option disables DNS lookups. We’re getting closer:

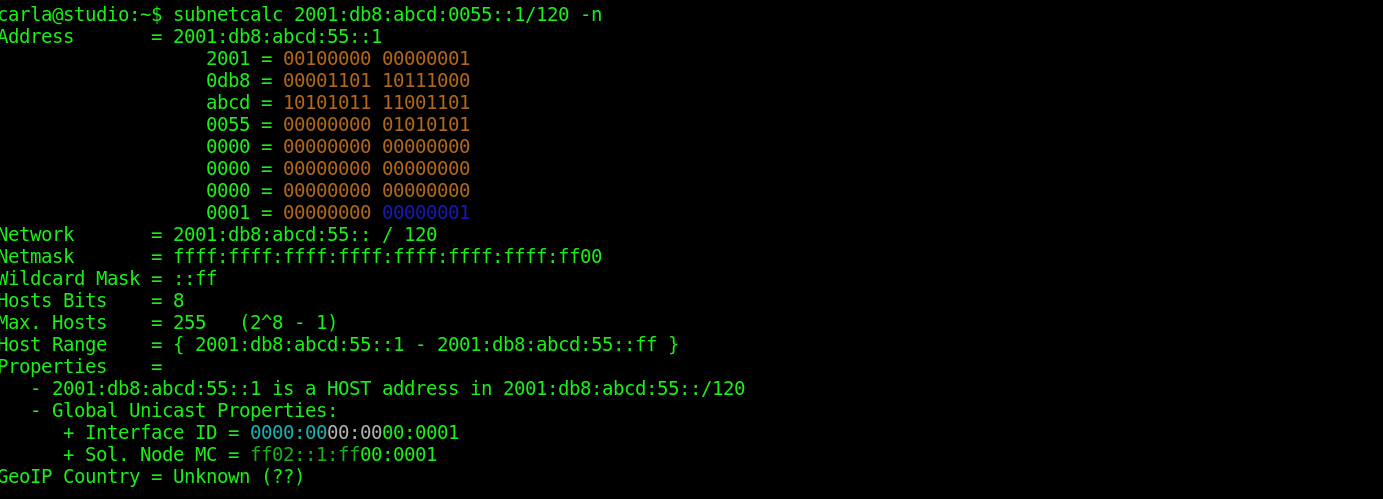

$ subnetcalc 2001:db8:abcd::0/120 -n

Address = 2001:db8:abcd::

2001 = 00100000 00000001

0db8 = 00001101 10111000

abcd = 10101011 11001101

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

0000 = 00000000 00000000

Network = 2001:db8:abcd:: / 120

Netmask = ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ff00

Wildcard Mask = ::ff

Hosts Bits = 8

Max. Hosts = 255 (2^8 - 1)

Host Range = { 2001:db8:abcd::1 - 2001:db8:abcd::ff }

Properties =

- 2001:db8:abcd:: is a NETWORK address

255 hosts works for me. So, while this isn’t quite as easy as ipcalc spelling out multiple subnets at once, it’s still useful. You might want to copy the Range blocks/IPv6 table and keep it close as a handy reference. It prints out the complete 2000::/3 range in a nice table, and also explains the math.

Next week, we’ll learn about networking in KVM, and using virtual machines to quickly and easily test various networking scenarios.

Learn more about Linux through the free “Introduction to Linux” course from The Linux Foundation and edX.