In today’s stupendous roundup, we will dig into the beloved lshw (list hardware) and lsusb (list USB) commands. This is a wonderful rabbit hole to fall down and get lost in as you learn everything about your hardware down to minute details, without ever opening the case.

lshw

The glorious lshw (list hardware) command reveals, in excruciating detail, everything about your motherboard and everything connected to it. It’s a tiny little command, weighting in at a mere 639k, and yet it reveals much. If you run lshw with no options you get a giant data dump, so try storing the results in a text file for leisurely analysis, and run it with root permissions for complete results:

$ sudo lshw | tee lshw-output.txt

The -short option prints a summary:

$ sudo lshw -short

H/W path Device Class Description

===========================================

system To Be Filled By O.E.M.

/0 bus H97M Pro4

/0/0 memory 64KiB BIOS

/0/b memory 16GiB System Memory

/0/b/0 memory DIMM [empty]

/0/b/1 memory 8GiB DIMM DDR3 Synchronous 1333 MHz (0.8 ns)

I assembled this system, so there is no OEM description. On my Dell PC it says “Precision Tower 5810” (0617).

This abbreviated example displays the hardware paths, which are the bus addresses. The output is in bus order. /0 is system/bus, your computer/motherboard. /0/n is system/bus/device. You can see these in the filesystem with ls -l /sys/bus/*/*, or look in /proc/bus. The lshw output tells you exact locations, like which memory slots are occupied, and which ports your SATA drives are connected to.

The Device column displays devices such as USB host controllers, hard drives, network interfaces, and connected USB devices.

The Class column contains the categories of your devices, and you can query by class. This example displays all storage devices, including a USB stick:

$ sudo lshw -short -class storage -class disk

H/W path Device Class Description

=========================================================

/0/100/14/1/3/4 scsi6 storage Mass Storage

/0/100/14/1/3/4/0.0.0 /dev/sdc disk 4027MB SCSI Disk

/0/100/1f.2 storage 9 Series Chipset Family

SATA Controller [AHCI Mode

/0/1 scsi0 storage

/0/1/0.0.0 /dev/sda disk 2TB ST2000DM001-1CH1

/0/2 scsi2 storage

/0/2/0.0.0 /dev/sdb disk 2TB SAMSUNG HD204UI

/0/3 scsi4 storage

/0/3/0.0.0 /dev/cdrom disk iHAS424 B

Use -volume to show all of your partitions.

In the first example I see my motherboard model, H97M Pro4, but I don’t remember anything else about it. No worries, because I can call up excruciatingly detailed information by omitting the -short option:

$ sudo lshw -class bus

*-core

description: Motherboard

product: H97M Pro4

vendor: ASRock

physical id: 0

serial: M80-55060501382

Check it out, the serial number, vendor, and everything. Consult the fine man page, man lshw, and see Hardware Lister (lshw) for detailed information on what all the fields mean.

lsusb

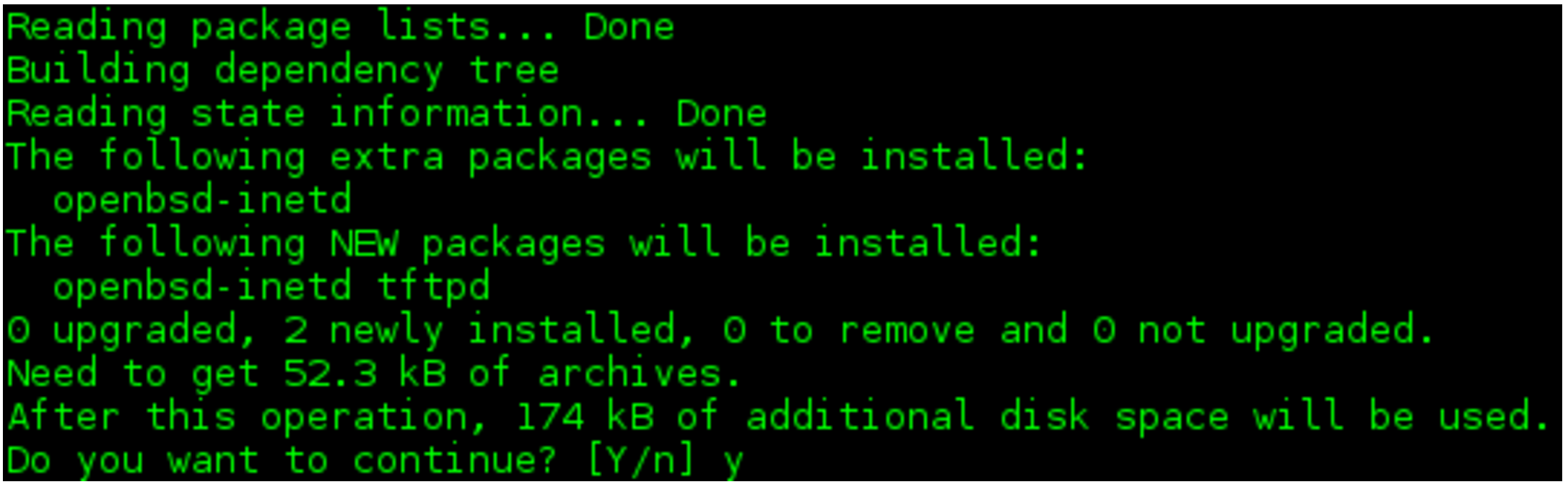

The usbutils suite of commands probes your USB bus and tells you everything about it. This includes usb-devices, lsusb, and usbhid-dump. openSUSE and CentOS also package lsusb.py, but don’t include any documentation for it. My guess is it’s obsolete as it was last updated in 2009, so let us move on to the freakishly useful lsusb:

$ lsusb Bus 002 Device 002: ID 8087:8001 Intel Corp. Bus 002 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub Bus 001 Device 002: ID 8087:8009 Intel Corp. Bus 001 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub Bus 004 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0003 Linux Foundation 3.0 root hub Bus 003 Device 003: ID 148f:5372 Ralink Technology, Corp. RT5372 Wireless Adapter Bus 003 Device 004: ID 046d:c018 Logitech, Inc. Optical Wheel Mouse Bus 003 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub

This may be all you ever need to verify what USB devices are connected to your system, and whether it is seeing all of them.

It also tells us a lot of interesting details, starting with bus assignments. The above output is on an older system that includes both 3.0 and 2.0 controllers, which may seem odd because USB standards are always backwards-compatible. But some 2.0 devices had problems with 3.0 controllers, so it made sense to have both.

There are only two external USB devices in the above output, a Ralink wi-fi dongle and a USB mouse. What are all those other things?

The root hub is a virtual device that represents the USB bus. Its device number is always 001, and the manufacturer is always 1d6b: Linux Foundation. The device ID tells us the USB standard, so 1d6b:0002 is a USB 2.0 bus, and 1d6b:0003 is USB 3.0.

In the above output there are two physical host controllers: 8087:8001 Intel Corp. USB 2.0) and 8087:8009 Intel Corp. (USB 3.0). On this system this is the Intel 9 Series Chipset Family Platform Controller Hub (PCH). This particular controller manages all I/O between the CPU and the rest of the system. There are no North and South bridges as there were in in the olden Intel days; everything is managed in a single chip. The architecture is rather interesting, and you can read all the endless details in the 815-page datasheet. The pertinent bits for this article are as follows.

There are two physical EHCI host controllers (USB 2.0), and one xHCI host controller (USB 3.0). You can see this more clearly with the tree view:

$ lsusb -t

/: Bus 04.Port 1: Dev 1, Class=root_hub, Driver=xhci_hcd/6p, 5000M

|__ Port 4: Dev 2, If 0, Class=Mass Storage, Driver=usb-storage, 5000M

/: Bus 03.Port 1: Dev 1, Class=root_hub, Driver=xhci_hcd/14p, 480M

|__ Port 5: Dev 13, If 0, Class=Vendor Specific Class, Driver=rt2800usb, 480M

|__ Port 12: Dev 4, If 0, Class=Human Interface Device, Driver=usbhid, 1.5M

/: Bus 02.Port 1: Dev 1, Class=root_hub, Driver=ehci-pci/2p, 480M

|__ Port 1: Dev 2, If 0, Class=Hub, Driver=hub/8p, 480M

/: Bus 01.Port 1: Dev 1, Class=root_hub, Driver=ehci-pci/2p, 480M

|__ Port 1: Dev 2, If 0, Class=Hub, Driver=hub/6p, 480M

This reveals all manner of fascinating information. It displays the kernel drivers, the USB versions of the connected devices (1.5M = USB 1.1, 480M = USB 2.0, and 5000M = USB 3.0), classes, busses, ports, and device numbers. There are four buses because the xHCI controller manages both USB 2.0 and 3.0 devices. lspci more clearly shows three physical host controllers:

$ sudo lspci|grep -i usb 00:14.0 USB controller: Intel Corporation 9 Series Chipset Family USB xHCI Controller 00:1a.0 USB controller: Intel Corporation 9 Series Chipset Family USB EHCI Controller #2 00:1d.0 USB controller: Intel Corporation 9 Series Chipset Family USB EHCI Controller #1

The physical USB ports that you plug your devices into are supposed to be color-coded. 3.0 is blue, and 2.0 ports are black. However, not all vendors use colored ports. No worries, just use a 3.0 device and lsusb to map your ports.

You may query specific buses, devices, or both. This example queries bus 004 and displays detailed information on the bus and connected devices:

$ sudo lsusb -vs 004:

You may query by vendor and product code:

$ sudo lsusb -vd 148f:5372

Update the ID database:

$ sudo update-usbids

You can also update the lspci database:

$ sudo update-pciids

See man lsusb for complete options, and thank you for joining me on this trip down the Linux hardware discovery rabbit hole.

Learn more about Linux through the free “Introduction to Linux” course from The Linux Foundation and edX.