This is the first article in our Test Driving OpenStack series. If you’re interested in learning how to run OpenStack, check out OpenStack training from The Linux Foundation.

Here’s a scenario. You’ve been hearing much about OpenStack and you’re interested in putting it through a test drive so you can start learning it. Perhaps you want to learn it to further your career, or perhaps you want to test it out to see if it’s something that would fit into your infrastructure. Either way, you want to get it up and running, but with one important requirement: Minimal or zero cost if possible.

Here’s a scenario. You’ve been hearing much about OpenStack and you’re interested in putting it through a test drive so you can start learning it. Perhaps you want to learn it to further your career, or perhaps you want to test it out to see if it’s something that would fit into your infrastructure. Either way, you want to get it up and running, but with one important requirement: Minimal or zero cost if possible.

Before we begin, let’s address that final requirement. There are many ways you can get up and running at no cost, provided you already have some hardware. But if you don’t have the hardware, you can still get going at minimal cost using cloud servers. The servers you use won’t have to be production-grade servers, but they’ll be enough to learn OpenStack.

OpenStack is technically just an API specification for managing cloud servers and overall cloud infrastructures. Different organizations have created software packages that implement OpenStack. To use OpenStack, you need to acquire such software. Fortunately, there are several free and open source solutions. (There are also premium models available, as well as free software, that come with premium support models.)

Since OpenStack is for managing cloud infrastruture, to get a minimal setup, you need two machines: One will be the infrastructure you’re managing, and one will be the manager. But if you’re really strapped for hardware, you can fit both on a single machine. Today’s computers allow for virtualization whereby you can run multiple server instances on a single machine. Of course, the more cores you have, the better; a quad-core is probably the minimum. So if you’re working on single-core computer, you probably will want to grab some space on a hosted server. If you have a dual-core computer, you’ll still be a bit tight for CPU space, and I recommend renting a server. But you can do it on your dual core if you have no other choice and just want to test out the basic functionality.

OpenStack Software and APIs

Although OpenStack is technically a specification, the OpenStack community has created a base set of software that you can use to get started trying it out. This software, called DevStack, is primarily intended for testing and development purposes, and not for production. But it includes everything you need to get going, including management tools.

The management tools are where things become a bit fuzzy between OpenStack being “just an API” and a set of software that makes use of the API. Anyone can technically build a set of software that matches the OpenStack specification. That software can be either on the managed side, or the manager side. The managed side would implement the API allowing any OpenStack-compliant management tool to manage it. The manager side would be a tool that can manage any OpenStack-compliant platform. The managed side is where OpenStack mostly lives with its various APIs. There are several APIs, but here are a couple:

Compute is the main API for allocating and de-allocating servers. The code name for this API is Nova. (Each portion of OpenStack includes a code name.) OpenStack also allows you to create and manage images that represent backups of disk drives. This portion of OpenStack is called Glance. These images are often going to contain operating systems such as Linux. The idea here is that you can choose an image that you’ll use to create a new server. The image might contain, for example, an Ubuntu 14.04 server that’s already configured with the software you need. Then you would use the Compute server to launch a couple of servers using that image. Because each server starts from the same image, they will be identical and already configured with the software you placed on the image.

In addition to the APIs living on the “managed” side, you’ll need a tool on the “manager” side to help you create servers. (This process is often referred to as provisioning servers.) The OpenStack community has created a very good application called Horizon, which is a management console. Although I mentioned that the free software is good for testing and development, the Horizon tool is actually quite mature at this point and can be used for production. Horizon is simply a management console where you click around and allocate your servers. In most production situations, you’ll want to perform automated tasks. For that you can use tools such as Puppet or Chef. The key is that any tool you use needs to know how to communicate with an OpenStack API. (Puppet and Chef both support OpenStack, and we’ll be looking at those in a forthcoming article.)

Up and Running

Knowing all this, let’s give it a shot. The steps here are small, but you’ll want to keep in mind how these steps would scale to larger situations and the decisions you would need to make. One important first decision is what services you want to use. OpenStack encompasses a whole range of services beyond the compute and image APIs I mention earlier. Another decision is how many hardware servers i.e. “bare metal servers” you want to use, as well as how many virtual machines you want to allow each bare metal server to run. And finally, you’ll want to put together a plan whereby users have limits or quotas on the amount of virtual machines and drive space (called volumes) they can use.

For this article we’re going to keep things simple by running OpenStack on a single machine, as this is an easy way to practice. Although you could do this on your own everyday Linux machine, I highly recommend instead creating a virtual machine so that you aren’t modifying your main work machine. For example, you might install Ubuntu 14.04 in VirtualBox. But to make this practice session as simple as possible, if you want you can install a desktop version of Ubuntu instead of the server version and then run the Horizon console right on that same machine. As an alternative, you can instead create a new server on a cloud hosting service, and install Ubuntu on it.

Next, you’ll need to install git. You don’t need to know how to actually use git; it’s just used here to get the latest version of the DevStack software. Now create a directory to house your OpenStack files. Switch to that directory and paste the following command into the console:

git clone https://git.openstack.org/openstack-dev/devstack

This will create a subdirectory called devstack. Switch to the new devstack, and then switch to the samples directory under it, like so:

cd devstack/samples

This directory contains two sample configuration files. (Check out OpenStack’s online documentation page about these configuration files.) Copy these up to the parent devstack directory:

cp local* ..

Now move back up to the parent devstack directory:

cd ..

Next, you need to make a quick modification to the local.conf file that you just copied over. Specifically you need to add your machine’s IP address within the local network. (It will likely start with a 10.) Open up local.conf using your favorite editor and uncomment (i.e. remove the #) the line that looks like this:

#HOST_IP=w.x.y.z

and replace w.x.y.z with your IP address. Here’s what mine looks like:

HOST_IP=10.128.56.9

(If you’re installing OpenStack, you probably know how to find your ipaddress. I used the ifconfig program.)

Now run the setup program by typing:

./stack.sh

If you watch, you’ll see several apt-get installations taking place followed by overall configurations. This process will take several minutes to complete. At times it will pause for a moment; just be patient and wait. Eventually you’ll see a message that the software is configured, and you’ll be shown a URL and two usernames (admin and demo) and a password (nomoresecrete).

Note, however, that when I first tried this, I didn’t see that friendly message, unfortunately. Instead, I saw this message:

“Could not determine a suitable URL for the plugin.”

Thankfully, somebody posted a message online after which somebody else provided a solution. If you encounter this problem, here’s what you need to do. Open the stack.sh file and search for the text OS_USER_DOMAIN_ID. You’ll find this line:

export OS_USER_DOMAIN_ID=default

and then comment it out by putting a # in front of it:

#export OS_USER_DOMAIN_ID=default

Then a few lines down you’ll find this line:

export OS_PROJECT_DOMAIN_ID=default

which you’ll similarly comment out:

#export OS_PROJECT_DOMAIN_ID=default

Now you can try again. (I encourage you at this point to read the aforementioned post and learn more about why this occurred.) Then to start over you’ll need to run the unstack script:

./unstack.sh

And then run stack.sh again:

./stack.sh

Finally, when this is all done, you’ll be able to log into the Horizon dashboard from the web browser using the URL printed out at the end of the script. It should just be the address of your virtual machine followed by dashboard, and really you should be able to get to it just using localhost:

http://localhost/dashboard

Also, depending on how you’ve set up your virtual machine, you can log in externally from your host machine. Otherwise, log into the desktop environment on the virtual machine and launch the browser.

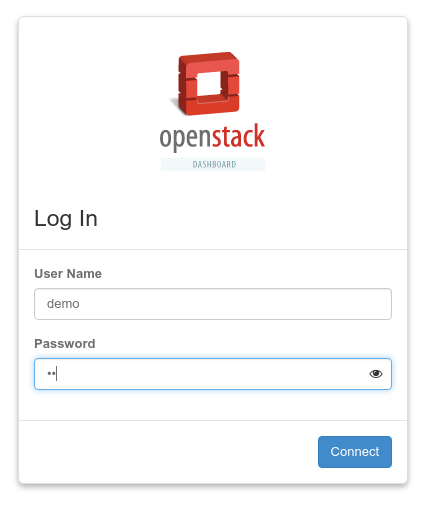

You’ll see the login page like so:

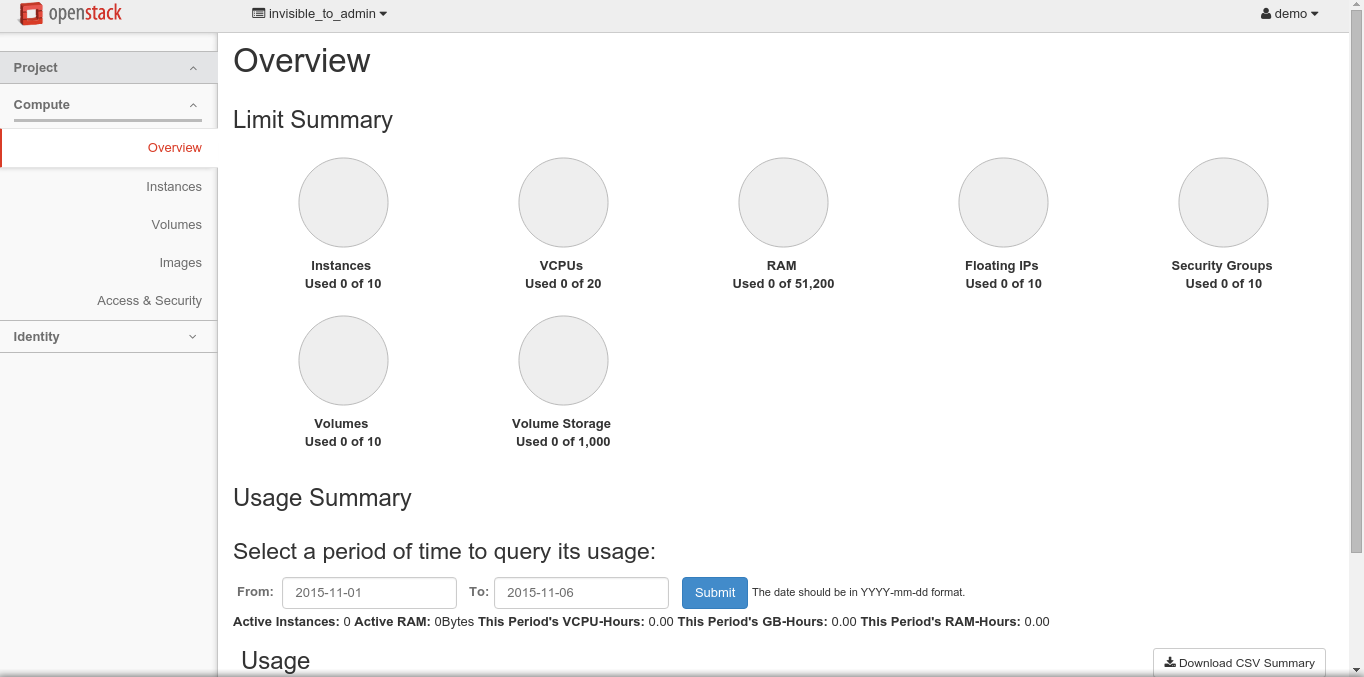

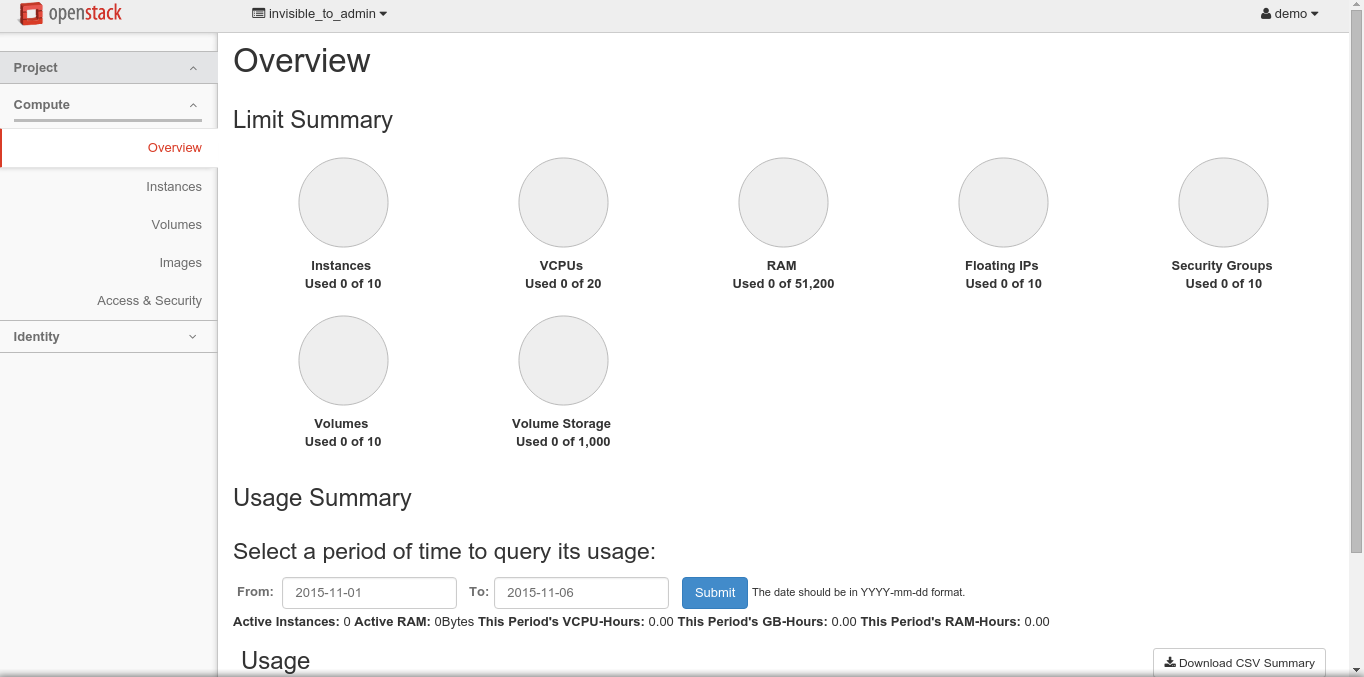

Use the username demo and password nomoresecrete. This will bring up the main dashboard:

The OpenStack Dashboard

At this point you can begin using the dashboard. There are different steps here to learn about managing the OpenStack system; for example, you can allocate a virtual machine. But before you do that, I recommend clicking around and becoming familiar with the various aspects of the dashboard. Also, keep in mind what this dashboard really is: It’s a web application running inside Apache Web Server that makes API calls into your local OpenStack system. Don’t confuse the dashboard with OpenStack itself; the dashboard is simply a portal into your OpenStack system. You’ll also want to log in as the administrator, where you’ll have more control over the system, including the creation of projects, users, and quotas. Spend some time there as well.

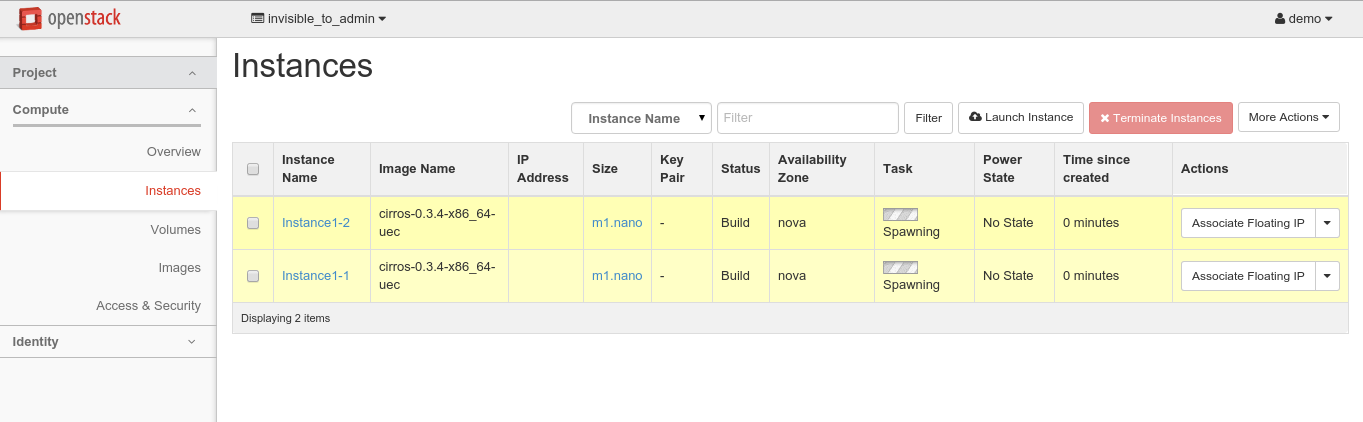

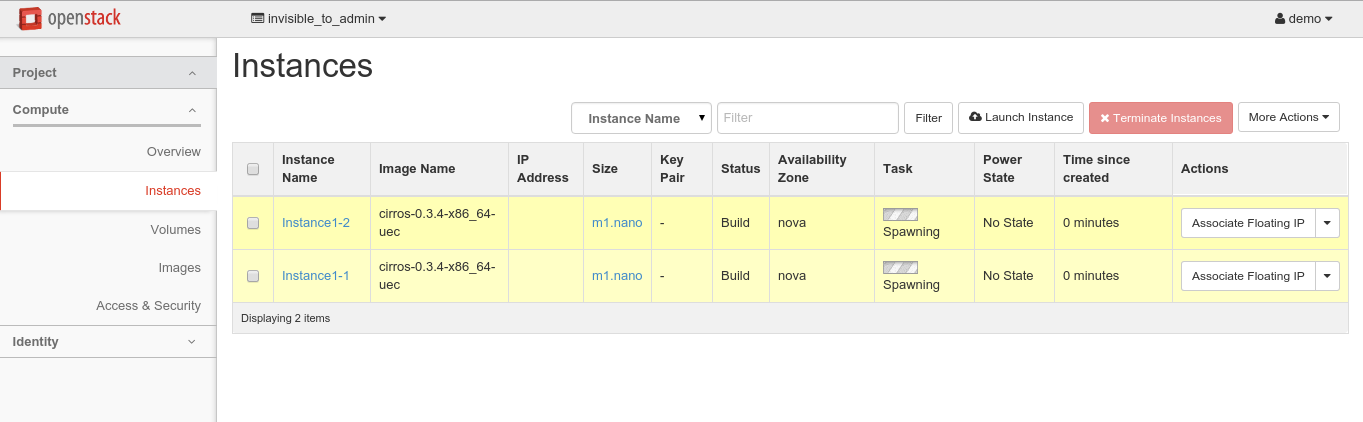

Want to allocate a couple virtual machines? Here are the basic steps to get started; you’ll want to spend more time practicing this. First, log back in as the demo user. Yes, we’re going to allocate a virtual machine within our virtual machine (hence the fact that this is only for testing purposes). On the left, click Instances:

Then click the Launch Instance button in the upper-right. Work through the wizard, filling in the details. Leave Availability Zone set to Nova. Name your instance, such as Instance1. Choose a flavor. Since you’re running a virtual machine, and it’s just a test, I recommend going with the smallest flavor, m1.nano. For Instance Count, you can do 1 or 2, whichever you like. For Instance Boot Source, choose Boot from Image. The Image Name option refers to the image you’re going to create your server from. There will be just one to choose; its name will be the word cirros followed by some version numbers.

Leave the other tabs with their defaults. For this test, let’s keep it simple by not providing a security key for logging into the instances. Now click the Launch button and you’ll see the progress of the machines launching:

This might take a while since you’re probably getting a little tight for system resources (as I was). But again, this is just a test, after all.

The Task column will show “Spawning” as the instances are starting up. Eventually, if all goes well, the instances will boot up.

That’s about all it takes to get up and running with OpenStack. There are some pesky details, but all in all, it’s not that difficult. But remember that you’re using just a developer implementation of OpenStack called DevStack. This is just for testing purposes, and not for production. But it’s enough to get you started playing with OpenStack. In the next article we explore automation with OpenStack using a couple of popular tools, Chef and Puppet. Read Tools for Managing OpenStack.

Learn more about OpenStack. Download a free 26-page ebook, “IaaS and OpenStack – How to Get Started” from The Linux Foundation Training. The ebook gives you an overview of the concepts and technologies involved in IaaS, as well as a practical guide for trying OpenStack yourself.

Read the previous article in this series: Going IaaS: What You Need to Know

It might sound weird to hear yourself talk with your computer, but that’s exactly where we’re going, and Mycroft is going to help us get there.

It might sound weird to hear yourself talk with your computer, but that’s exactly where we’re going, and Mycroft is going to help us get there.

From the developer who brought us the RaspEX and RaspAnd Live CDs, RaspArch aims to be a tool that lets anyone install the latest Arch Linux operating system on Raspberry Pi 2 single-board computers without too much hassle.

From the developer who brought us the RaspEX and RaspAnd Live CDs, RaspArch aims to be a tool that lets anyone install the latest Arch Linux operating system on Raspberry Pi 2 single-board computers without too much hassle.

Here’s a scenario. You’ve been hearing much about

Here’s a scenario. You’ve been hearing much about