By Thierry Escande, Senior Software Engineer at Collabora.

Kmemleak (Kernel Memory Leak Detector) allows you to track possible memory leaks inside the Linux kernel. Basically, it tracks dynamically allocated memory blocks in the kernel and reports those without any reference left and that are therefore impossible to free. You can check the kmemleak page for more details.

This post exposes real life use cases that I encountered while working on the NFC Digital Protocol stack.

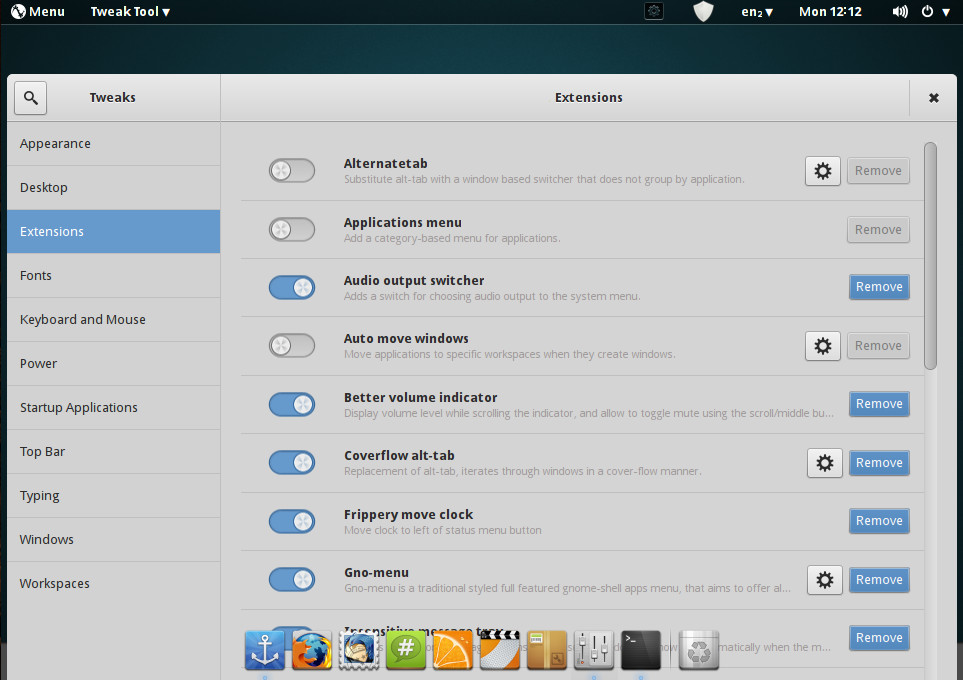

Enabling kmemleak in the kernel

kmemleak can be enabled in the kernel configuration under Kernel hacking > Memory Debugging.

[*] Kernel memory leak detector

(4000) Maximum kmemleak early log entries

< > Simple test for the kernel memory leak detector

[*] Default kmemleak to off

I used to turn it off by default and enable it on demand by passing kmemleak=on to the kernel command line. If some leaks occur before kmemleak is initialized you may need to increase the “early log entries” value. I used to set it to 4000.

The sysfs interface of kmemleak is a single file located in /sys/kernel/debug/kmemleak. You can control kmemleak with the following operations:

Trigger a memory scan:

$ echo scan > /sys/kernel/debug/kmemleak

Clear the leaks list:

$ echo clean > /sys/kernel/debug/kmemleak

Check the possible memory leaks by reading the control file:

$ cat /sys/kernel/debug/kmemleak

I will not go deep regarding the various NFC technologies and the following examples will be based on NFC-DEP, the protocol used to connect 2 NFC devices and make them communicate through standard POSIX sockets. DEP stands for Data Exchange Protocol.

For the purpose of this post I’m using nfctool, a standalone command line tool used to control and monitor NFC devices. nfctool is part of neard, the Linux NFC daemon.

So let’s start with an easy case.

A simple case: leak in a polling loop

When putting a NFC device in target polling mode, it listens for different modulation modes from a peer device in initiator mode. When I first used kmemleak I was surprised to see possible leaks reported by kmemleak while not even a single byte has been exchanged, simply by turning target poll mode on the nfc0 device.

$ nfctool -d nfc0 -p Target

A few seconds later, after a kmemleak scan using:

$ echo scan > /sys/kernel/debug/kmemleak

The following message appear in the syslog:

[11764.643878] kmemleak: 8 new suspected memory leaks (see /sys/kernel/debug/kmemleak)

OK! Check the kmemleak sysfs file then:

$ cat /sys/kernel/debug/kmemleak

unreferenced object 0xffff9be0f8f43a08 (size 8):

comm "kworker/0:1", pid 41, jiffies 4297830116 (age 16.044s)

hex dump (first 8 bytes):

01 fe d3 80 ca 41 f1 a0 .....A..

backtrace:

[] kmemleak_alloc+0x4a/0xa0

[] kmem_cache_alloc_trace+0xf5/0x1d0

[] digital_tg_listen_nfcf+0x3b/0x90 [nfc_digital]

[] digital_wq_poll+0x5d/0x90 [nfc_digital]

[] process_one_work+0x156/0x3f0

[] worker_thread+0x4b/0x410

[] kthread+0x109/0x140

[] ret_from_fork+0x25/0x30

[] 0xffffffffffffffff

This gives the call stack where the allocation has been actually done. So let’s have a look at digital_tg_listen_nfcf()…

int digital_tg_listen_nfcf(struct nfc_digital_dev *ddev, u8 rf_tech)

{

int rc;

u8 *nfcid2;

rc = digital_tg_config_nfcf(ddev, rf_tech);

if (rc)

return rc;

nfcid2 = kzalloc(NFC_NFCID2_MAXSIZE, GFP_KERNEL);

if (!nfcid2)

return -ENOMEM;

nfcid2[0] = DIGITAL_SENSF_NFCID2_NFC_DEP_B1;

nfcid2[1] = DIGITAL_SENSF_NFCID2_NFC_DEP_B2;

get_random_bytes(nfcid2 + 2, NFC_NFCID2_MAXSIZE - 2);

return digital_tg_listen(ddev, 300, digital_tg_recv_sensf_req, nfcid2);

}

The only allocation here is the nfcid2 array, passed to digital_tg_listen() as 4th parameter, a user argument supposed to be returned as a function argument to the callback digital_tg_recv_sensf_req() upon reception of a valid frame from the peer device or if a timeout error occurs (nobody on the other side is talking to us). After a quick check in digital_tg_recv_sensf_req() it appears that the user argument is not used at all and of course not released.

As I said, that one was easy. There was no need for the nfcid2 array to be allocated in the first place so the fix was pretty straightforward.

Now digital_tg_listen_nfcf() looks good:

int digital_tg_listen_nfcf(struct nfc_digital_dev *ddev, u8 rf_tech)

{

int rc;

rc = digital_tg_config_nfcf(ddev, rf_tech);

if (rc)

return rc;

return digital_tg_listen(ddev, 300, digital_tg_recv_sensf_req, NULL);

}

The commit for this fix can be found here.

Another use case for leaks hunting was about un-freed socket buffers.

Continue reading on Collabora’s blog.