Linux serves — of that there is no doubt — literally and figuratively. The open source platform serves up websites across the globe, it serves educational systems in numerous ways, and it also serves the medical and scientific communities and has done so for quite some time.

I remember, back in my early days of Linux usage (I first adopted Linux as my OS of choice in 1997), how every Linux distribution included so many tools I would personally never use. Tools used for plotting and calculating on levels I’d not even heard of before. I cannot remember the names of those tools, but I know they were opened once and never again. I didn’t understand their purpose. Why? Because I wasn’t knee-deep in studying such science.

Modern Linux is a far cry from those early days. Not only is it much more user-friendly, it doesn’t include that plethora of science-centric tools. There are, however, still Linux distributions for that very purpose — serving the scientific and medical communities.

Let’s take a look at a few of these distributions. Maybe one of them will suit your needs.

Scientific Linux

You can’t start a listing of science-specific Linux distributions without first mentioning Scientific Linux. This particular take on Linux was developed by Fermilab. Based on Red Hat Enterprise Linux, Scientific Linux aims to offer a common Linux distribution for various labs and universities around the world, in order to reduce duplication of effort. The goal of Scientific Linux is to have a distribution that is compatible with Red Hat Enterprise Linux, that:

-

Provides a stable, scalable, and extensible operating system for scientific computing.

-

Supports scientific research by providing the necessary methods and procedures to enable the integration of scientific applications with the operating environment.

-

Uses the free exchange of ideas, designs, and implementations in order to prepare a computing platform for the next generation of scientific computing.

-

Includes all the necessary tools to enable users to create their own Scientific Linux spins.

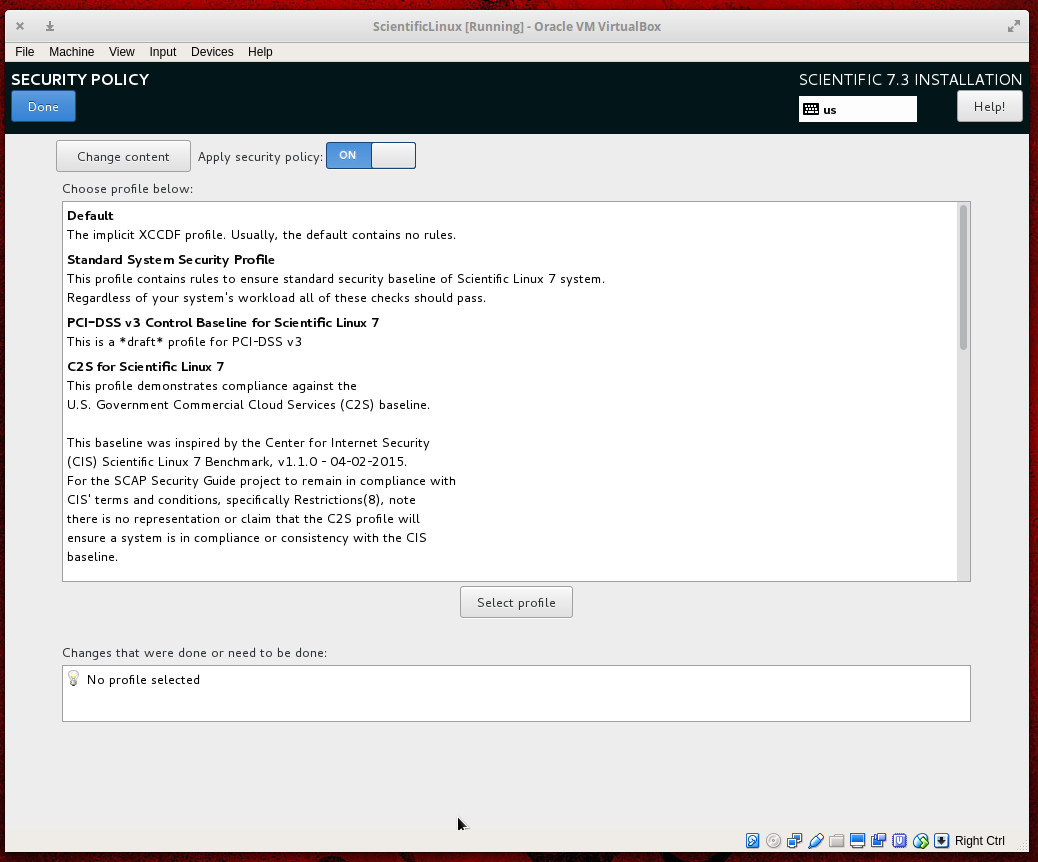

Because Scientific Linux is based on Red Hat Enterprise Linux, you can select a Security Policy for the platform during installation (Figure 1).

Two famous experiments that work with Scientific Linux are:

-

Collider Detector at Fermilab — experimental collaboration that studies high energy particle collisions at the Tevatron (a circular particle accelerator)

-

DØ experiment — a worldwide collaboration of scientists that conducts research on the fundamental nature of matter.

What you might find interesting about Scientific Linux is that it doesn’t actually include all the science-y goodness you might expect. There is no Matlab equivalent pre-installed, or other such tools. The good news is that there are plenty of repositories available that allow you to install everything you need to create a distribution that perfectly suits your needs.

Scientific Linux is available to use for free and can be downloaded from the official download page.

Bio-Linux

Now we’re venturing into territory that should make at least one cross section of scientists very happy. Bio-Linux is a distribution aimed specifically at bioinformatics (the science of collecting and analyzing complex biological data such as genetic codes). This very green-looking take on Linux (Figure 2) was developed at the Environmental Omics Synthesis Centre and the Natural Environment for Ecology & Hydrology and includes hundreds of bioinformatics tools, including:

-

abyss — de novo, parallel, sequence assembler for short reads

-

Artemis — DNA sequence viewer and annotation tool

-

bamtools — toolkit for manipulating BAM (genome alignment) files

-

Big-blast — The big-blast script for annotation of long sequence

-

Galaxy — browser-based biomedical research platform

-

Fasta — tool for searching DNA and protein databases

-

Mesquite — used for evolutionary biology

-

njplot — tool for drawing phylogenetic trees

-

Rasmo — tool for visualizing macromolecules

There are plenty of command line and graphical tools to be found in this niche platform. For a complete list, check out the included software page here.

Bio-Linux is based on Ubuntu and is available for free download.

Poseidon Linux

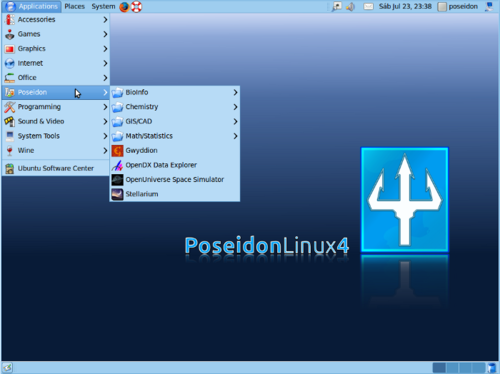

This particular Ubuntu-based Linux distribution originally started as a desktop, based on open source software, aimed at the international scientific community. Back in 2010, the platform switched directions to focus solely on bathymetry (the measurement of depth of water in oceans, seas, or lakes), seafloor mapping, GIS, and 3D visualization.

Yes, Poseidon Linux is a very niche distribution, but if you need to measure the depth of water in oceans, seas, and lakes, you’ll be glad it’s available.

Download Poseidon Linux for free from the official download site.

NHSbuntu

A group of British IT specialists took on the task to tailor Ubuntu Linux to be used as a desktop distribution by the UK National Health Service. NHSbuntu was first released, as an alpha, on April 27, 2017. The goal was to create a PC operating system that could deliver security, speed, and cost-effectiveness and to create a desktop distribution that would conform to the needs of the NHS — not insist the NHS conform to the needs of the software. NHSbuntu was set up for full disk encryption to safeguard the privacy of sensitive data.

NHSbuntu includes LibreOffice, NHSMail2 (a version of the Evolution groupware suite, capable of connecting to NHSmail2 and Trust email), and Chat (a messenger app able to work with NHSmail2). This spin on Ubuntu can:

-

Perform as a Clinical OS

-

Serve as an office desktop OS

-

Be used as in kiosk mode

-

Function as a real-time dashboard

The specific customizations of NHSbuntu are:

-

NHSbuntu wallpaper (Figure 4)

-

A look and feel similar to a well-known desktop

-

NHSmail2 compatibility

-

Email, calendar, address book

-

Messager, with file sharing

-

N3 VPN compatibility

-

RSA token supported

-

Removal of games

-

Inclusion of Remmina (Remote Desktop client for VDI)

NHSbuntu can be downloaded, for free, for either 32- or 64-bit hardware.

The tip of the scientific iceberg

Even if you cannot find a Linux distribution geared toward your specific branch of science or medicine, chances are you will find software perfectly capable of serving your needs. There are even organizations (such as the Open Science Project and Neurodebian) dedicated to writing and releasing open source software for the scientific community.

Learn more about Linux through the free “Introduction to Linux” course from The Linux Foundation and edX.