The large ecosystem of add-on boards is a key factor in the success of the Raspberry Pi, which torched the competition in our recent hacker board reader survey. Much of the Pi add-on business has moved to the Raspberry Pi Foundation’s HAT (Hardware Attached on Top) I/O specification, which launched in 2014 as an easier, more standardized way to extend the Pi’s 40-pin expansion connector.

Below is a roundup of 10 of the most interesting and highly regarded HATs on the market. This is not a review, but rather a selection intended to reflect the amazing diversity of Pi HATs. We have skipped numerous application segments here, especially in the purely industrial market and in basic accessories like touchscreens and cameras. It should also be noted that there are many excellent Pi add-ons that do not follow the HAT specification.

Compared to traditional Pi add-ons or shields, HATs, which are often called bonnets in the UK, are automatically recognized by the SBC. With the help of a pair of I2C EEPROM pins, the HAT works with the Pi to automatically configure the GPIOs and drivers. The 65x56mm HAT daughter-cards stack neatly on top of the SBC next to the Ethernet and USB ports. This reduces cable clutter and allows both Pi and HAT to fit into standard enclosures. HATs also provide mounting holes that match up with the standard RPi B+, 2, and 3.

To focus this roundup, I have omitted the fast-growing segment of smaller, Raspberry Pi Zero-sized pHATs (partial HATs), most of which also work on regular-sized Pis. I have also skipped the well-known “official” Raspberry Pi add-ons such as the 7-inch touchscreen HAT and Sense HAT.

Below are summaries of our top 10 HATs, with links to product pages:

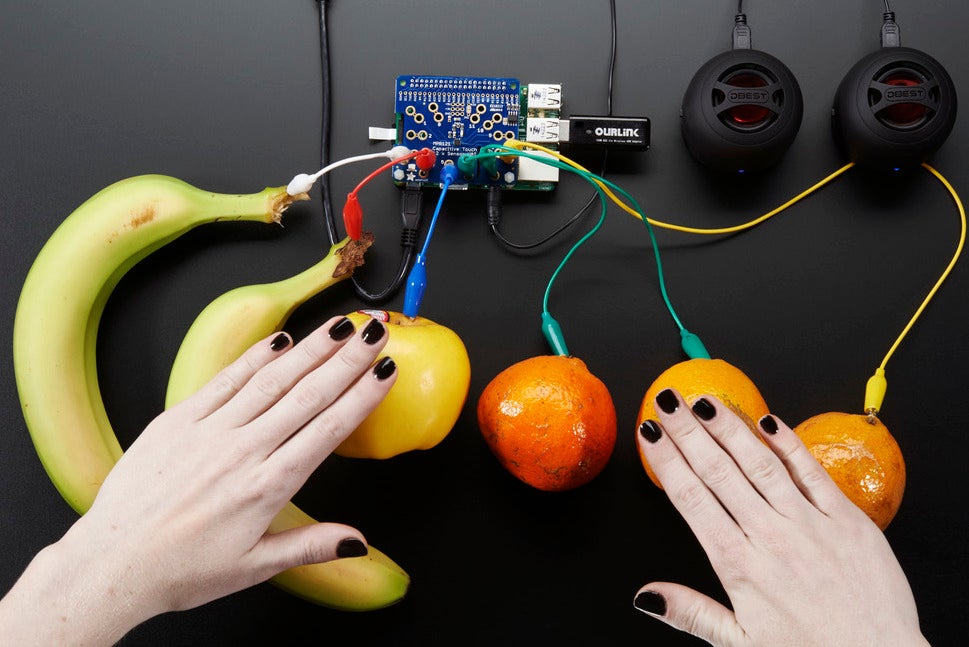

Adafruit Capacitive Touch HAT — Adafruit (New York) — $14.95

Adafruit is a good place to start your HAT hunt, as it sells dozens of Adafruit and third-party HAT models. The Adafruit Capacitive Touch HAT should not be confused with the many capacitive and resistive touchscreen add-ons for the Raspberry Pi. The Touch HAT has no display, but is instead designed to turn a variety of objects into touch sensors. The HAT supplies 12 sensors with alligator clip cables that can be attached to any electrically conductive object, such as metal, or any water-filled object such as fruit. A Python library can detect each touch and can help you connect the inputs to things like keyboards and speakers. Nothing like a fruit drum to liven up the breakfast table.

Adafruit 16-Channel PWM/Servo HAT — Adafruit (New York) — $17.50

The 16-Channel PWM/Servo HAT is designed for controlling robots and other gizmos with moving parts. It can control 16 servos or PWM outputs over I2C “with perfect timing,” claims Adafruit. An onboard PWM controller, which operates at up to 1.6KHz with 12-bit precision, can drive all 16 channels simultaneously “with no additional Raspberry Pi processing overhead,” claims the company. You can stack up to 62-boards to control up to 992 servos. The HAT supports 5V servos that can accept 3.3V logic level signals, and ships with a 2-pin terminal block, four 3×4 headers, a 2×20 socket header, and a Python library.

Flick HAT — Pi Supply (UK) — 20 Pounds ($25.70)

Pi Supply’s Flick HAT, which also sells at ModMyPi can detect gestures from up to 15cm (5.9 inches) away and track movement in 3D space for controlling apps, TV, music, and more. Open source libraries enable gestures like swipe, tap, airwheel, and touch. The electrical near-field sensing technology, which is based on a Microchip MCG3130 gesture chip, even lets you hide the Flick behind non-conductive material. There’s also a Flick Zero pHAT model, as well as a Flick Large that can work with other I2C-enabled boards.

HealthyPi — ProtoCentral (India)

You may still have time to get in on the $195 HealthyPi Crowd Supply campaign, which ends July 14. This multi-parameter patient monitoring HAT kit features temperature, pulse oximetry, and ECG/respiration sensors, as well as 20 adhesive electrodes. A full $395 kit adds an RPi 3, touchscreen, an isolated power adapter, a case, and a 16GB card. The HealthyPi is built around an Atmel ATSAMD21 Cortex-M0 MCU, and ships with an Arduino Zero bootloader. There are no certifications such as FDA approval, but the device can be used for DIY home health monitoring, emerging nations healthcare, education, research, and medical device prototyping.

Pi-DAC+ — IQaudIO (UK) — 30 Pounds ($38.50)

Like most audio add-on cards for the Pi, the Pi-DAC+ is built on TI’s “Burr Brown” PCM5122 DAC (Digital to Analog Converter) chip. The chip provides 12/106-dB stereo DAC conversion with a 32-bit, 384kHz PCM Interface and Linux drivers. Unlike the original Pi-DAC, IQaudIO’s + model integrates a 24-bit/192kHz “full HD” headphone amplifier. This well-documented HAT provides hardware volume control and ESD protection.

Pilot — Linkwave (UK) — 94.80 (w/tax) or 79 Pounds ($121.80 or $101.50)

If your project is far from the madding crowd, the RPi 3’s WiFi won’t do you much good. Linkwave’s “Pilot” HAT gives you a Sierra Wireless HL 3G/HSPA radio, a micro-SIM slot, as well as a SiRFstar V GNNS location chip with GPS and GLONASS. The Pilot speaks to the Raspberry Pi using serial or USB links, with separate channels for control, data, and location. That means most of the 40 expansion pins are still available. You can also transfer data to the Sierra Wireless AirVantage IoT Platform via MQTT for a device-to-cloud data aggregation setup.

Pimoroni Automation HAT — Pimoroni (UK) — 29 Pounds ($37.30)

Pimoroni is one of the major HAT makers, and it also sells HATs from other vendors. Its Automation HAT is designed for home monitoring and automation control, and can be used to create gizmos like smart sprinklers and fish feeding systems. The device features 3x 24V @ 2A relays, 3x 12-bit ADCs @ 0-24V, and a 12-bit ADC @ 0-3.3V. Other I/O includes 3x 24V tolerant buffered inputs and 3x 24V tolerant sinking outputs. You also get 15x LEDs so you can see what’s going on with each I/O channel. As usual, Pimoroni provides a custom Python library. The HAT is also available at Adafruit.

Pimoroni Unicorn HAT — Pimoroni (UK) — 24 Pounds ($36 at Amazon)

The popular Unicorn HAT is a programmable, 8×8 RGB array with 64 LEDs, billed as “the most compact pocket aurora available.” The multi-color lighting gizmo can be used for mood-lighting, 8×8 pixel art, status indications, and “persistence of vision effects,” as well as an elemental programming tool with instant gratification. The Unicorn HAT ships with a Python API, and can be powered directly from the Pi, although it needs a “good 2A power supply.”

UPS PIco — Pi Modules (Greece) — 29.48 Euros ($33.80)

This open source, uninterruptible power supply makes sure your Pi-based project stays online even when the power flutters or fades. There are several different versions, starting with the UPS PIco HV3.0A 450 mAh Stack. If the 450mAh LiPO battery with its 10 to 15 minutes of backup power is not enough, or you can upgrade to 4000mAh or 8000 mAh models. The system safely shuts down the Pi during cabled power cut, and offers automatic system restart when power is restored. The UPS Pico provides wide-range 7-to-28V DC input, making it usable in vehicles, and it’s designed to support adjustable battery charging from solar power input. Other features include a serial port, as well as event-triggered remote startup.

503HTA Hybrid Tube Amp — Pi 2 Design (Rhode Island) — $159

Unlike low-cost audio DAC add-ons such as the Pi-DAC+, the 503HTA Hybrid Tube Amp goes for a retro — and many would say, richer — sound that’s totally tubular. The 24-bit, 112db THD PCM5102A DAC supports both 12AU7 (ECC82) or 6922/6DJ8 (ECC88) type audio tubes, and uses the Pi’s I2S interface to drive a single 12AU7 tube gain stage at a 192Khz frame rate. Using headphones connected to the 3.5mm jack, you can generate 32 to 300 ohms audio, and there’s a gain select switch with 2V, 4V, and 6V rms settings. The full set-up requires an external 48W+ power supply. The 503HTA ships with Volumio and OSMC open source media players, with plans to add Rune Audio.

Learn more about embedded Linux at Open Source Summit North America — Sept. 11-14 in Los Angeles, CA. Register by July 30th and save $150! Linux.com readers receive a special discount. Use LINUXRD5 to save an additional $47.